All of us are extremely fortunate that a number of highly professional photographers were active in this area during and immediately after the Klondike Gold Rush. Eric A. Hegg, Harrie C. Barley, William H. Case and Horace H. Draper (Case & Draper), Asahel Curtis, Lloyd V. Winter and Edwin P. Pond (Winter & Pond), Anton Vogee among others are legends to Klondike historians for providing such excellent views of the human drama of the gold rush. Frank La Roche was one of those amazing men and who I believe was also the first professional photographer to reach Skagway at the very beginning of the gold rush.

La Roche was born in Philadelphia on June 20, 1853. He began his photographic career there at 17 and two years later opened his own shop. His parents, Aaron and Anna La Roche, were of French and German ancestry. Frank worked as a commercial photographer in Florida, Iowa and Utah and even paid a visit to California in 1888, earning multiple awards along the way for his photographs before finally arriving in Seattle just after the great fire of June 1889. The city was in ashes but he soon opened up a gallery in the Kilgen Block on Second Avenue. In addition to high-class portrait photography, La Roche specialized in scenic and industrial views of western Washington State. He produced an extensive series of views of Seattle, its waterfront, streets and buildings. He photographed ships, logging activities and Native Americans in the area. He traveled throughout the western United States and along the Canadian Pacific Railway, taking numerous scenic views which he sold to tourists. From 1890-1902 La Roche made over 100 photographic trips to Alaska and so was well acquainted with the area years before the great gold rush started. He married Miss Ida M. Crary in 1891 and they had a son, La Roche Jr., who assisted his father in the studio as soon as he could.

Klondike fever struck Seattle, and soon the rest of the world, with the arrival of the Steamer Portland (July 17, 1897) and the Seattle Post-Intelligencer’s famous story that day about a ton of gold that was aboard the ship along with a headline that screamed, “GOLD” four times across Page 1. La Roche quickly realized the potential of the gold rush to his business and immediately booked passage on one of the first ships heading north to Alaska after the arrival of the Portland, the Pacific Steamship Company’s Steamer Queen. The SS Queen, filled with eager Klondike stampeders and somewhat bewildered tourists, arrived at the bay that would soon be called Skagway on July 26, 1897.

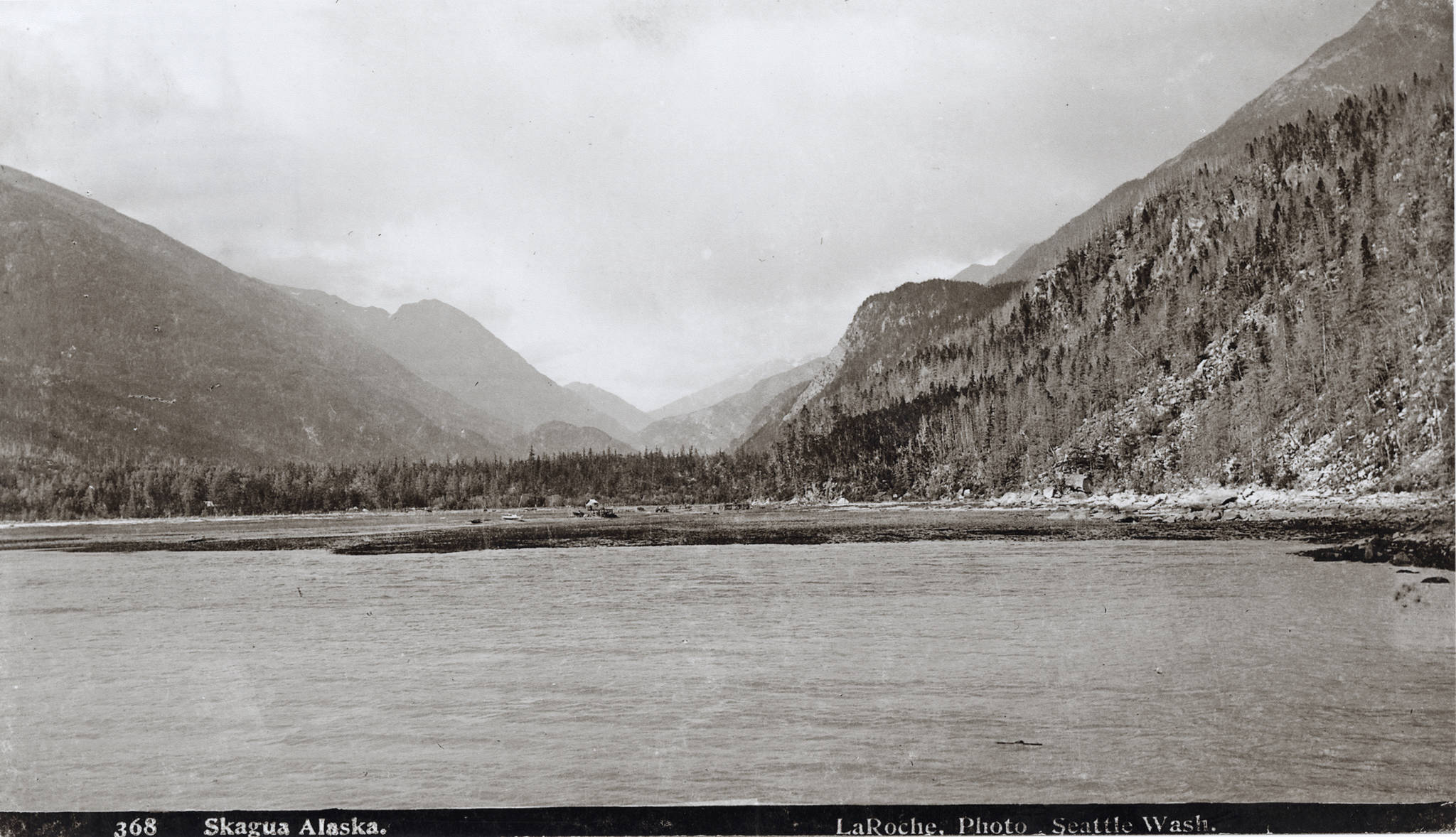

In the morning of that day, even before the gold rush, Argonauts and their outfits were hoisted off the Queen, La Roche set up his camera on the deck of the ship and took a photograph of the bay and the Skagway valley behind — the calm before the storm. The original image, now on file at the Library of Congress, has exquisite detail. The tide is out and a rowboat and small sail boat (Ben Moore’s Gertrude) sit, tilted, on the tide flat at the mouth of Mill Creek. Nearby, in the middle of the image, is a small landing platform, on timber piers, high above the water line and loaded with supplies. A wagon with two horses is to the left, opposite the creek.

Directly behind the platform, is Moore’s cabin and in front of the cabin, his son Ben Moore’s wood-frame house under construction (both buildings have been restored by the National Park Service). The cabin sits at the edge of the tree line and a broad beach flat spreads out before it. A wagon is shown following the original White Pass Trail between the house and the platform. Stretching across the center of the image is a barbed wire fence. A cow or two are visible grazing on the grasses of the flat land.

Moore’s unroofed sawmill can be seen at right with workers on its ramp. On the far right, along the rocky valley sidewall is a tent and a log cabin under construction. On the left (west) side of the image, barely visible between the trees, is the roof of Moore’s Hotel, at the modern intersection of Fifth Avenue and State Street. Moore’s Hotel is today called the Portland House and has been restored. Two or three tents are in the trees between the Moore cabin and the hotel. This placid scene shows primeval Skagway on the brink. This is one of the few pictures of Mooresville, as Moore called his little hamlet, just before the invading hoard of stampeders changed its name to Skagway and changed the destiny of this little valley forever.

During the ensuing weeks and months, La Roche traveled about and took many famous and not-so-famous photographs documenting the early days of the rush and the rapid changes Skagway and the surrounding area was undergoing because of the invasion. He snapped the many ships in the Skagway harbor before the wharfs were built and the stampeders and their outfits being offloaded. He took the first photograph of Broadway, a dirt track lined by a sea of tents and stampeders. We know it is Broadway because a sign painter has erected a street sign by his tent. The sign clearly shows the name Broadway but the name of the cross street is hidden. Based on the tree line in the background, the photographer was probably standing a little south of Fourth Avenue. This has recently be confirmed by the discovery of another photograph, not taken by La Roche, showing the back side of the sign with the name of Bond Street, now known as Fourth Avenue. La Roche snapped his picture on Aug. 12, 1897.

In October 1897 La Roche took what is probably one of the first overview photographs of Skagway from high on the mountainside near lower Dewey Lakes. He also snapped the “Montana Kid” and his dog team at Fifth Avenue and Broadway after the “Kid” had made the journey from Dawson City to Skagway in 24 days. He moved over to Dyea and photographed Chiefs Don-a-wok and Isaac in front of their building with the sign that advertised their trade – “Packing a Specialty.” Then he took a photograph of 40 Native canoes pulled up on a beach alongside the Native village in Dyea.

La Roche hiked up the Chilkoot Trail in the early fall of 1897 and took many pictures along the way including one of three Native packers resting in front of a couple of oxen loaded with supplies, several men pushing and pulling a 1200 pound outfit loaded on a flat-bottom boat up the Taiya River, camp life at Finnegan’s Point, several actresses fording the Taiya River and later relaxing at Happy Camp. He photographed an endless line of men and horses blocked by a fallen horse on the “summer trail” between Canyon City and Pleasant Camp. One of La Roche’s pictures of Sheep Camp shows a scattering of tents, many tree stumps and a light dusting of snow. It also shows Jack London. Most of his photographs of the Scales and the Summit region show the area devoid of snow, with only a few stampeders indicating they were taken early in the rush but he did manage to catch at least one photograph of men climbing up the snow covered Golden Stairs.

La Roche also took pictures of the White Pass Trail. He photographed several of the first log bridges over the Skagway River and then Main Street in Rag Town – which appears to have been today’s Liarsville, a Bla cksmith Shop along the trail and the Hungry Man’s Retreat, a restaurant in a tent at Porcupine Creek. A number of his photographs taken in the “picturesque forest” outside of Skagway show a very rough trail that would soon be called the Dead Horse Trail for the many horses that died along it, in Jack London’s famous phrase “like mosquitoes in the first frost.” He also took many photographs of Lindeman and Bennett, where the two trails end, including pictures of boats being built and used on the lakes and all of his images show the area months before the main tide of gold rush humanity washed over the two communities leaving a sea of tents.

His photographs show that La Roche reached Dawson and the Klondike gold fields during the early part of the rush. Although it is possible that he wintered over in Dawson, he was back in Seattle by early March 1898 in time to take pictures of the Reindeers and the Laplanders that were part of the United States Yukon Relief Expedition intended to relieve the starving miners of Dawson. By the time the few surviving Reindeer actually made it to Dawson a year or so later, the miners were no longer starving and hadn’t been for a year. Then he was back on the Chilkoot Trail to photograph the aftermath of the April 3, 1898 avalanche and then back in Seattle, taking pictures of the Cooper & Levy store piled high with supplies bound for the Klondike and the Steamer Roanoke with miners returning from the Klondike taken on July 19, 1898. On his trips back and forth from Seattle, he also took pictures of various Southeast Alaska towns such as Wrangell, Sitka and Juneau.

Although historians have not been able to document all of his trips, once Skagway was established, La Roche seems to have traveled back to the city on some of his subsequent Alaskan trips. He took photographs of a much more substantial Broadway and the new White Pass & Yukon Route railroad in the summer of 1899. He also visited Skagway in the summers of 1900 and 1901 to document the many changes that had taken place since his first photograph of Mooresville on that fateful morning in 1897.

On Sunday, July 14, 1901, La Roche set up a newfangled motion picture camera on Broadway to record the passing scene. According to the Daily Alaskan newspaper article published a few days later, “Several prominent officials of the railroad, who were hurrying down to their offices, were caught in life-like positions as well as a few prominent merchants out for a Sunday morning stroll.” Where that motion picture is today, I do not know but if you hear about it, please let me know.

La Roche made a good living selling mounted prints of his travels to the tourists, but he reached a wider audience through his souvenir album entitled Enroute to the Klondike. This was published in 1898 and was one of the earliest printed works to depict the harrowing journey faced by the gold-hungry hordes.

La Roche won several gold medals for his pictures at the Alaska-Yukon Pacific Exposition in Seattle in 1909 and was their official photographer. Around 1914, he moved his studio to the town of Sedro-Wooley, north of Seattle and retired there in 1928.

Finally, on April 12, 1936, La Roche died. He left his studio to his son but left a lasting historic legacy to all of us that lives on to this very day.”

• Karl Gurcke is a Skagway historian who works at the National Park Service. He can be reached at karl_gurcke@nps.gov. Information for this program was supplied in part by Frank La Roche’s book entitled “En Route to the Klondike: Chilkoot Pass and Skaguay Trail” (1898), biographical notes found on-line at the University of Washington, the Everett Public Library, and Archives West web pages, an unpublished manuscript by Robert L. Spude entitled “The White Pass Trail across Block 24, 1888-1897” (2003), and Daily Alaskan newspaper articles dated May 1, 1900, June 15, 1900, June 15, 1901 and July 16, 1901. If you have or know about any photographs of Skagway and vicinity taken by Frank La Roche or other historic photographers, please let him know about them. An earlier version of this article was read over the air on KHNS, the Haines public radio station.