Alaska Native organizations are divided in their stances on this fall’s Ballot Measure 1, and that divide was noticeable at a Tuesday afternoon forum devoted to discussing the measure.

The forum was hosted by Get Out the Native Vote Southeast and jointly sponsored by Sealaska Corporation, the Central Council of the Tlingit and Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska, and other organizations.

Sealaska and other Native corporations are asking their shareholders to vote against it. Central Council has not taken a stand on the measure, but other tribes, particularly in Bristol Bay, are urging a yes vote. That divide spreads across Alaska and is expected to be on display next week in Anchorage when the Alaska Federation of Natives hosts its annual meeting.

“This is, I think, one of the more challenging forums for me to prepare for,” forum moderator Sam Kito III said before the start of the event.

“This initiative can be divisive, even among friends or family,” he said.

Stand for Salmon, also known as Ballot Measure 1, asks voters to approve a complicated habitat permitting law for salmon-bearing waters within Alaska.

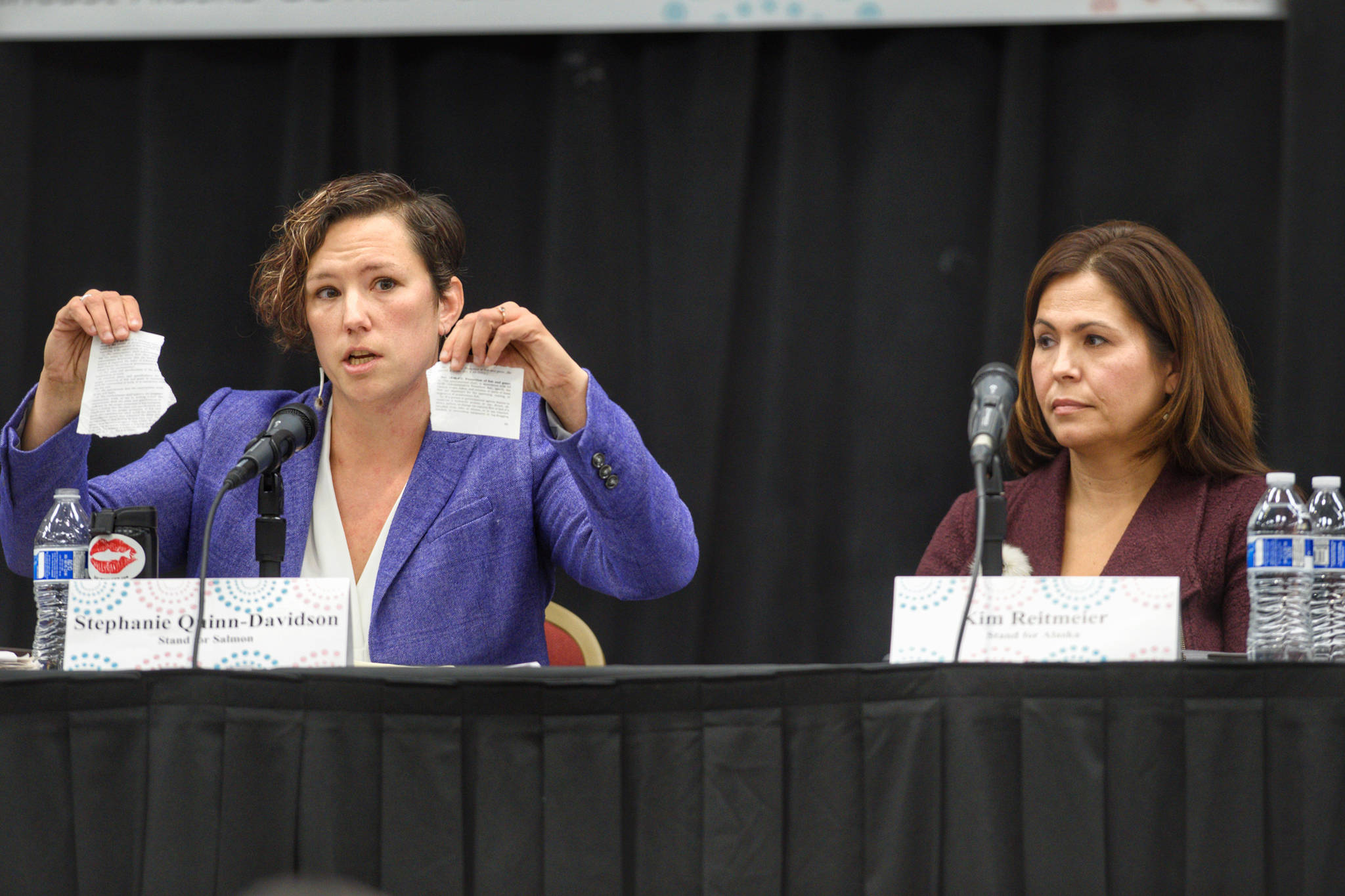

Speaking on behalf of Yes for Salmon, the organization promoting the measure, Stephanie Quinn-Davidson held up the state’s book of statutes, then a packet of loose pages that she said were the state’s fisheries laws.

“It’s because of this,” she said, holding the packet, “we’re able to get salmon to the spawning grounds.”

“What are we doing to actually protect those spawning grounds?” she asked.

She then held up two narrow strips of paper torn from that book of regulations.

Quinn-Davidson and Yes for Salmon contend that the state’s habitat protection laws are inadequate to protect salmon from the effects of mining, logging, construction and other development. As a result, that development is harming the state’s salmon returns.

Speaking on behalf of Stand for Alaska, which opposes the measure, was Kim Reitmeier, executive director of the ANCSA Regional Association, which represents all 12 active regional Native corporations in the state. As Reitmeier explained, Native corporations own 44 million acres of Alaska land, or 92 percent of the state’s private land.

“We deserve the right to manage our land … this takes that away from us,” she said.

Reitmeier said she agrees that salmon should be protected, but she disagrees that Ballot Measure 1 is the best way to do it. Passing the measure would have significant effects on Alaska’s economy because it would require additional paperwork and government inspection, thus adding cost and time to construction projects.

“We’re in a recession, we can’t afford that,” she said.

She went further, speculating that if the state is forced to spend more on permitting and regulation, it will spend less on education and support for rural communities.

Quinn-Davidson, who works for the Tanana Chiefs Conference as the director of the Yukon River intertribal fish commission and helped author the measure, said the measure will “probably” require developers to pay somewhat more, but she does not believe the effects will be as catastrophic as Reitmeier describes and that the cost will be worth it to protect a salmon industry that employs more than 32,000 people each year.

Reitmeier criticized the intiative for being drafted without input from a broader swath of Native leaders. No corporate leaders were consulted before its drafting, she said, and only a comparative handful of tribal representatives had input.

Quinn-Davidson responded that one of the key purposes of the intiative is to open a public process that allows that kind of input. Currently, the state may issue habitat permits without taking public comment. She referenced the recent award of 13 habitat permits to the Donlin Creek gold mine under development in southwest Alaska and said that under the ballot measure, communities and tribes would be able to discuss the project in a way they cannot today.

About 90 people were present at the forum and listened quietly to the discussion. There was no applause for either side as attendees ate salmon chowder served by Smokehouse Catering, a new Tlingit & Haida venture.

Millions of dollars are being spent promoting and opposing the ballot measure, which could surpass the 2014 vote on Senate Bill 21 as the most expensive in Alaska history.

According to figures released Tuesday, Yes for Salmon has raised $1.3 million and Stand for Alaska has raised $11.5 million.

Quinn-Davidson and Reitmeier each ended the discussion by urging Alaskans to go to the polls on Election Day, Nov. 6.

“No matter what you do at the ballot box, I encourage you to go to the ballot box,” Reitmeier said.

• Contact reporter James Brooks at jbrooks@juneauempire.com or 523-2258.