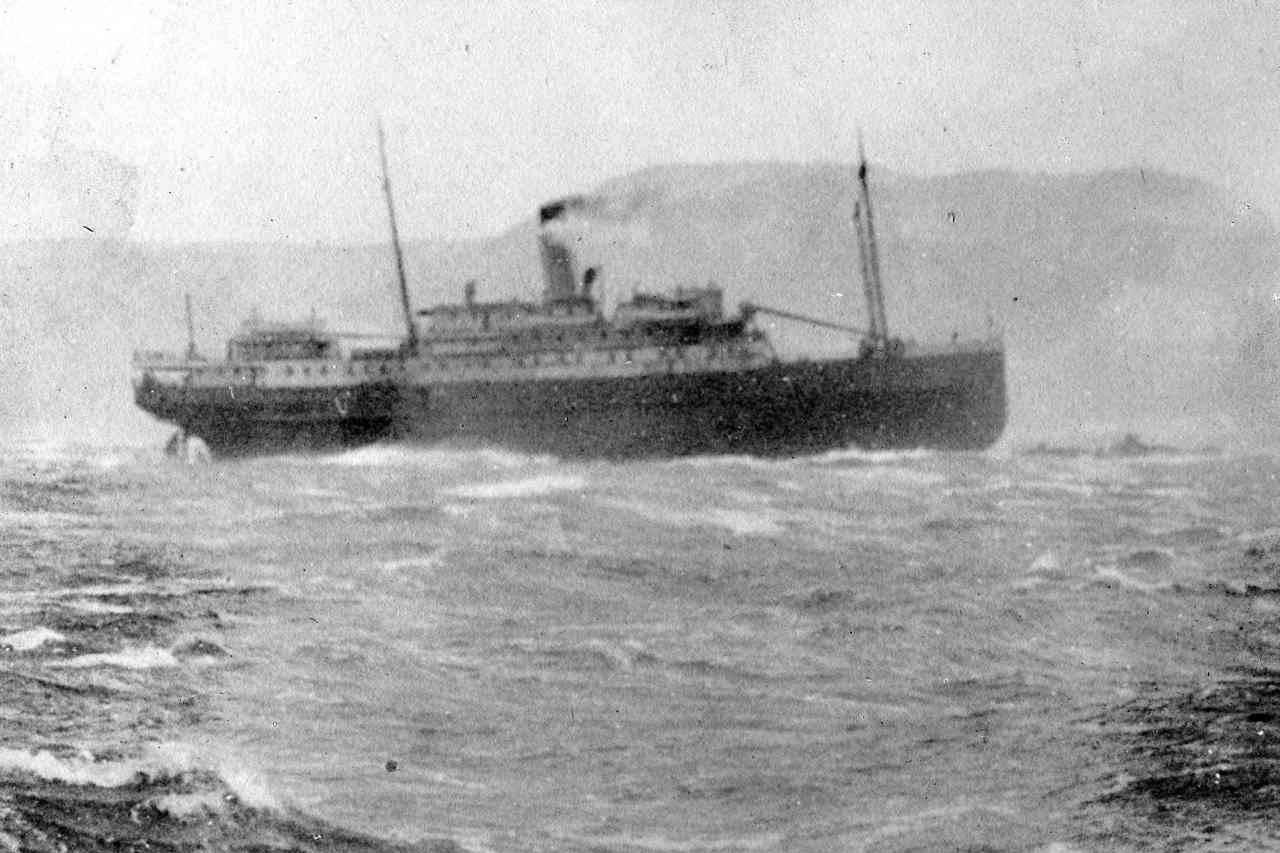

Perhaps a few of you are familiar with the history of the tragic sinking of the Princess Sophia, a Canadian Pacific Steamer, which occurred 100 years ago this month. Approximately six years after the sinking of the Titanic, the Princess Sophia, also named the “unknown Titanic of the West Coast,” remains the worst shipwreck on the west coast of North America.

There were no survivors in this catastrophic event. At least 353 passengers and crew lost their lives in the wintry waters near Vanderbilt Reef that year, yet, surprisingly few members of the general public know about this historic event. This could be attributed to the fact that the shipwreck occurred just days before the end of the First World War. Newspapers were highlighting the Armistice that ended the war and headlines were focused on the increasing fear of Spanish influenza rather than the news of a tragic shipwreck in Alaskan waters.

On Wednesday Oct. 23, 1918 the Daily Alaskan announced, “Steamer Princess Sophia leaves Skagway P.M. — Tickets Take Same Rate to: Vancouver, Victoria, Seattle, Tacoma, Olympia, Everett, Bellingham, Anacortes and Port Townsend.” At 10:10 pm on Oct. 23, 1918, the Princess Sophia departed Skagway on her last run of the season to Vancouver and Victoria, three hours behind schedule. The 353 aboard the Sophia included miners, territory and city government officials, businessmen, civil servants, their wives and children, and crew members. It was a diverse group representing individuals from the Yukon and Alaska.

Four hours into the journey out of Skagway, the Princess Sophia had shifted course. At 2 a.m. on Oct. 24, the Sophia crashed into Vanderbilt Reef at a speed of about 11 knots. With heavy snow, fog and zero visibility, her distance from the shore was most likely miscalculated. The question as to how the ship came to hit Vanderbilt Reef has not been answered definitively; the Sophia’s log was never found and all the ship’s officers perished.

It remains a matter of conjecture as to how exactly she got off course. The average speed for the Sophia was 11-12 knots, but given the weather conditions a speed reduction of 7 knots should have been taken. Likely to compensate for the late departure, Captain Leonard Locke had continued at 11 knots.

On the rocks

Upon striking Vanderbilt Reef, the ship’s wireless operator sent out a distress call to Juneau and a fleet of rescue vessels was quickly assembled in response. Rescuers circled the Sophia for several hours waiting to save passengers and crew.

The Sophia wasn’t taking on water initially and Captain Locke hoped the ship could float free off the reef at high tide. He reassured the passengers that they would be able to get off the reef, and not to panic. As for the rescue efforts, he did not want to risk lives in such rough water.

Passengers waited patiently through the 24th to the 25th for their rescue. Some wrote letters. Some were hopeful, while others were unsure of the true circumstances they were in. Auris McQueen wrote: “She is a double-bottom boat and her inner hull is not penetrated, so here we stick. She pounds some on a rising tide and it is slow writing, but our only inconvenience is, so far, lack of water. The main steam pipe got twisted off and we were without lights last night, and have run out of soft sugar. But the pipe is fixed so we are getting heat and lights now, and we still have lump sugar and water for drinking.”

Weather and seas only seemed to worsen. The combination of seas and tide made rescue efforts nearly impossible. The Cedar got within 400 yards of the Sophia, but its anchor would not attach to the bottom and rough waves forced them to turn back. The Daily Alaskan reported the “Lighthouse Tender Cedar found it impossible, owing to the high seas and the increasing storm to remove the passengers from the Princess Sophia after he had arrived at the scene of the wreck.”

Passengers on the Sophia began to realize the severity of their situation. Jack Maskell wrote: “Shipwrecked off coast of Alaska. S.S. Princess Sophia. 24th Oct 1918. My Own Dear Sweetheart, I am writing this dear girl while the boat is in grave danger. We struck a rock last night which threw many from their berths, women rushed out in their night attire, some were crying, some too weak to move, but the life boats were soon swung out in all readiness, but owing to the storm would be madness to launch until there was no hope for the ship….there are now seven ships near…. We are expecting the lights to go out any minute, also the fires. The boat might go to pieces, for the force of the waves are terrible, making awful noises on the side of the boat.”

In the afternoon, the storm became stronger and the rescue vessels had to seek refuge for themselves. A combination of strong winds and high tide lifted the Sophia’s stern off the reef, and when it came down, most of the hull was torn away. The ship pivoted and the bow was headed north – the Sophia began taking on water. The last SOS was sent at 5:20 p.m. on Oct. 25: “Taking water and foundering, for GOD’s sake come and save us!”

‘Could not be saved’

The Princess Sophia sat on Vanderbilt Reef for 40 hours in rough seas and storms. Between 5:30 and 6 p.m. on Oct. 25, the Princess Sophia sunk. Watches on the victims stopped at 6 p.m. At 8:30 a.m. on Oct. 26 once the storm had calmed, rescue boats returned to Vanderbilt Reef to find that all that was left of the Princess Sophia was 40 feet of foremast rising above the surface of the water. In a report from the Daily Alaskan, the Captain of the rescue ship King and Winge stated the “Sophia Passengers Lives could not be saved.”

In the aftermath of the shipwreck, the Daily Alaskan stated that, “Vanderbilt Reef has long been regarded as a menace to navigation.” Vanderbilt Reef, located about 30 miles north of Juneau, is about seven miles long. For the majority of the time, it lies just below the surface of Lynn Canal and is no more than 12 feet above the surface at any given time. In 1918, safety markers were limited; the Sentinel Island Lighthouse was four miles away and a buoy from U.S. coastal authorities was only visible in daylight. Canadian Pacific had submitted a request in 1917 for the installation of a light on the reef, but they were rejected due to lack of funds during times of war.

This tragedy emphasized the urgency for additional navigational aids in the Lynn Canal. Lengthy legal battles ensued in addition to feelings that more could have been done to prevent the disaster. At the end of inquiries, it was decided that all had been done by CPR and Captain Locke to save the lives of all aboard the Princess Sophia.

Alaska grieves

The Daily Alaskan of Dec. 5, 1918 editorialized about the tragedy: “Another terrible marine casualty…numberless human lives have found [a] resting place in the icy waters of those sparsely lighted and poorly protected shores. In the case of the Princess Sophia the loss of life is most appalling making it the most serious wreck of record on the Pacific. The vessel struck and held for a time on the rocks, but later broke in two … without one survivor. In all 343 are said to have been lost, and the monument over their final resting place is THE UNLIGHTED VANDERBILT REEF IN UNITED STATES WATERS. … A fairly new steel vessel of British build and registry, worth a million, possibly another million in gold dust, in addition to those precious human lives, mostly American, many Canadians and others — all lost and possibly could have been avoided. Oh, the pity of it! … Is it not the opportune moment for insisting that something be done to at least minimize the risk of such tragedies in those waters of British Columbia and Alaska?”

Alaska Territorial Governor Thomas Riggs, Jr., issued a statement: “Wreck of the Princess Sophia has cast great shadow over all of Northland. Alaska grieves with the Yukon.”

There were no survivors from the ship except a dog: an English Setter, covered in oil, was found at Tee Harbor, about 20 miles south of Vanderbilt Reef. For a time after the sinking, evidence washed ashore bit by bit. In early November, the Daily Alaskan reported that “The high south winds and rising tides will in all probability bring more pieces of the wreck and perhaps some bodies and a good watch should be kept up …This morning Henry Phillips [was] found on the beach near the mouth of the Skagway river [with] one of the Princess Sophia life preservers and a part of one of the hatch covers from the same boat.”

Just 10 days later another discovery was made and reported by the Daily Alaskan: “…while patrolling the peninsula below Haines found body in Mud Bay … was searched and papers found upon it identified the man as being William Haggerty. The papers found on the body were a passport issued at Dawson and a membership card in the Independent Order of Odd Fellows at Brawley, California …. body sent on Osprey to Juneau where it will be buried.”

Unsolved mystery

This tragedy remains an unsolved mystery. There were plenty of witnesses, particularly the captains of the rescue ships that had spent a day and a half circling the vessel on Vanderbilt Reef. Some of them were of the opinion that the passengers could have been taken off the ship, but the majority believed they would have been in considerable danger, and that it was not unreasonable for Locke to assume that his ship was in no immediate peril.

This “Unknown Titanic of the West Coast” is named partially because the story was hidden in the world news during the time, but also because of the missing details of the Princess Sophia’s demise; with no survivors, our understanding of what happened during those 40 hours after impact will never be confirmed in detail.

In remembrance

A ceremony to honor the SS Princess Sophia victims will be held in Skagway at the White Pass & Yukon Route depot at 1 p.m. on Oct. 20, followed by the unveiling of a memorial at Skagway Centennial Park at 2 p.m. A similar memorial was dedicated at Eagle Beach State Recreation area in Juneau this past summer. Special museum exhibits opened in Juneau and Skagway this summer, and one will open at the Yukon Arts Centre in Whitehorse on Oct. 25.

• Anne Lattka was the Skagway Student Conservation Association History Intern in 2016. This column was edited by Karl Burke, historian at the Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park. Information for this column was supplied by a book entitled The Sinking of the Princess Sophia: Taking the North Down With Her by Ken Coates and Bill Morrison (1990) (Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press), a website on The Sinking of the Princess Sophia by the British Columbia Maritime Museum, several issues of Skagway’s Daily Alaskan newspaper including those dated Nov. 7, 1918, Nov. 22, 1918, Dec. 17, 1918 and Jan. 11, 1919 and Jeff Brady. An earlier version of this article was read over the air on KHNS, the Haines public radio station.