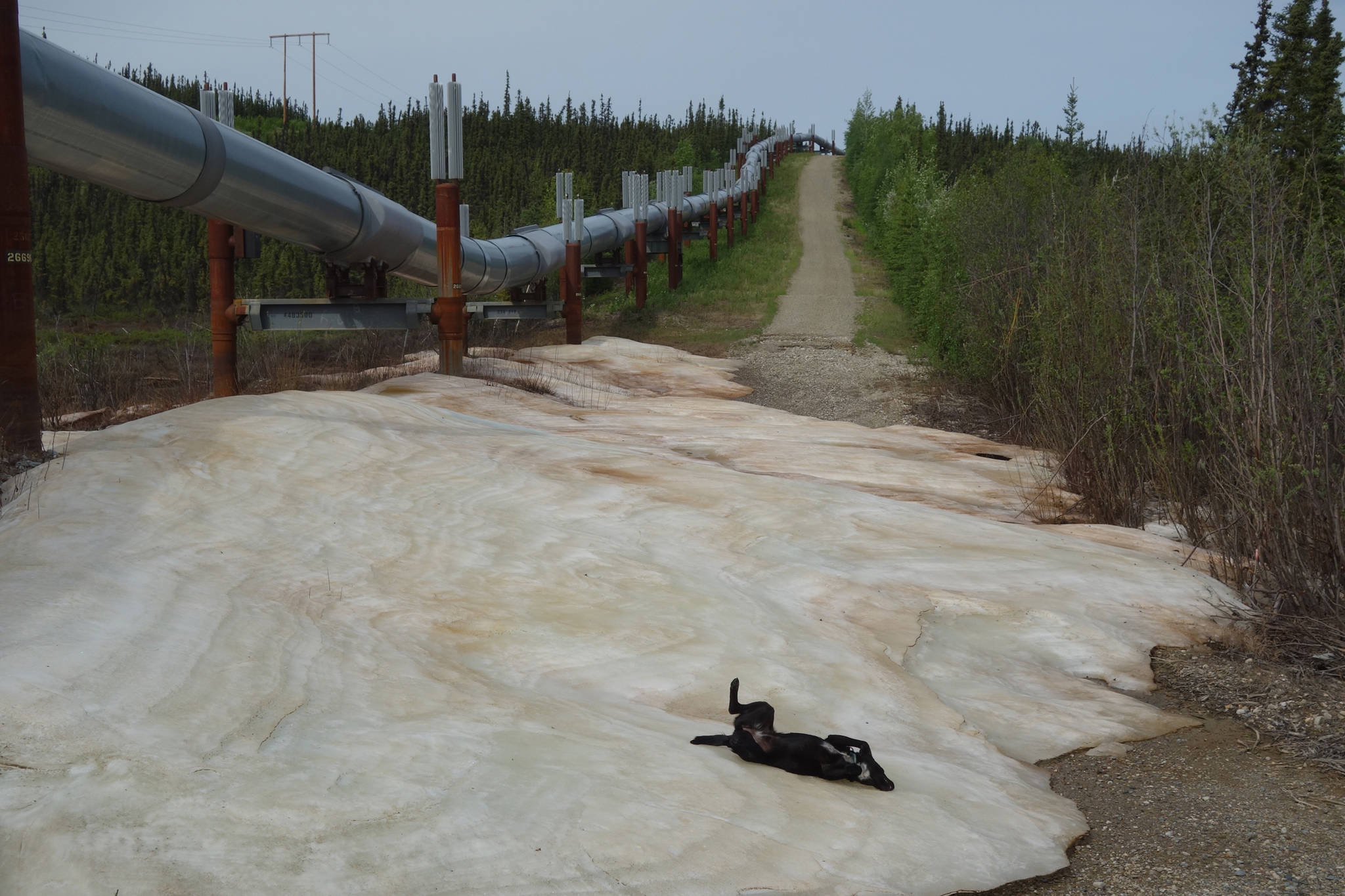

GOLD RUN CREEK — This clear waterway running through boreal swampland marks the farthest Cora and I will be from a highway during our summer hike along the route of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline.

If we chose to bust overland southwest toward Banner Creek, we would have to cover at least nine boggy miles before we reached the Richardson Highway. Backtracking to the nearest pipeline access road would require a hike of 20 miles.

What’s the significance of the most remote part of a pathway that is itself a manmade disturbance? Good point. Living out here this summer with lots of time to think, I find it interesting to be in a spot far from the distant hum of engines.

What is here? Swainson’s thrushes (the flutey sound of summer), olive-sided flycatchers, gray-cheeked thrushes and the thrush with the song that never gets old, the American robin.

Ice, in the form of aufeis over a few creeks, formed by the cold air of winter, is enduring well into the heat of summer. One such mini-glacier prevents truck or four-wheeler travel, making this spot feel even more isolated.

And the mosquitoes are here. They emerged in numbers sufficient to make me pull out the repellent. The blessed liquid that messes with the bloodsuckers’ carbon-dioxide detectors allowed me to enjoy dinner by Gold Run Creek. After 39 days without needing protection, I was due.

This country, bounded by the Salcha River to the north and Shaw Creek to the south, was the outer range of John Haines, one of the finest writers Alaska will ever inspire. His poetic essays about trapping and existing in the hills west of here define Interior Alaska.

The late storyteller once sent me a letter in response to a column I wrote about the shipping network that allows Alaskans to eat fresh broccoli in midwinter. Haines reflected on life in Alaska decades ago, eating honey created by northern bees, moose meat and potatoes. And about the lean times, with not enough skinny hares for the pot.

He was not thrilled with the prospect and then reality of this pipe running through his wilderness. But it came, it is here and always has been in my Alaska.

Gold Run Creek seems wild, even though I’m leaning against a vertical support member made of steel. It’s quiet enough for me, anyway. I get to see songbirds up close all day and, now through 40 days, have yet to see a bear.

That’s a siting I can do without. Haines wrote in his spare, slow cadence of shooting at a grizzly that charged him from a small creek bed not far from here. He perhaps wounded it. He didn’t know, and he found no blood. The bear retreated to the alders. Haines crossed the creek with his trusted sled dog and continued on to one of his trapline cabins. Later, he needed to again transit the creek and head for home at the Richardson Highway.

“If that bear was still somewhere in that dense green cover, nursing its hurt and its temper, waiting for revenge, it would have its chance,” he wrote in the essay “Out of the Shadows” from the book “The Stars, the Snow, the Fire.”

I think about bears many times each day, and more at night, when I stuff in earplugs to disable my radar. It seems to be the only way I can sleep. Then, I depend on Cora’s ears and nose, with my canister of pepper spray to the right of my pillow.

Everyone I meet seems to share a bear story. But I’m starting to think that the pipeline itself is a bear deterrent.

Biologists once collared a wolf near the Yukon River and followed its movements for a summer. The animal crossed the Yukon and Porcupine rivers, wandered to the Beaufort Sea coast, and drifted westward. Before it was found dead of starvation near the Kanuti River, that wolf had walked to the edge of the Dalton Highway a dozen times. But it never once crossed that road.

Maybe the association of manmade things with bad consequences keeps the big predators away from the pipeline. Wolf tracks are hard to find out here, as is bear sign. Moose tracks and encounters are plentiful, and we’ve seen several caribou. Hares and songbirds may be attracted to the shrubs and grasses along the pipeline.

Why is the pipe so far from the road here? I don’t know. Looking at the map, it seems pipeline designers used about 10 miles less of the four-foot diameter, half-inch steel pipe than if they had followed the Richardson Highway over the same distance. That material savings was probably trivial in a project of this size, but the decision has made these gurgling creeks and ancient black spruce part of the quietest landscape so far along the 800-mile route.

• Since the late 1970s, the University of Alaska Fairbanks’ Geophysical Institute has provided this column free in cooperation with the UAF research community. Ned Rozell is a science writer for the Geophysical Institute. This summer, he is hiking the path of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline from Valdez to Prudhoe Bay. He also did the trip 20 years ago.