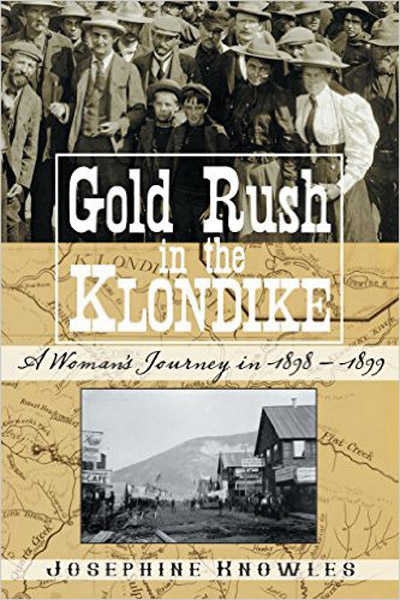

“Gold Rush in the Klondike,” written at the turn of the 20th century, tells the first person story of the gold-seeking exploits of the author’s family in the Yukon territory. Josephine Knowles passed down her fascinating little memoir to her grand-daughter shortly before she passed away in 1936 at the age of 71. Nearly 80 years later, her recovered journal about her odyssey in the Klondike gold camps finally made its way to print in the book I am now reviewing.

Her memoir traces the long and dangerous journey of her family from Oakland, California to Dawson City, Canada, adjacent to the Klondike’s gold fields. Their arduous trek meandered from Dyea to Sheep Camp to Lake Lindeman (all in Alaska) and finally to the roughly hewn, ramshackle town of Dawson, where the would-be gold miners set up camp. Not only does she relate the woes and hardships of surviving in the Klondike, she also does a splendid job of detailing the trip itself and the fellow travelers she and her husband meet along the way. One of those adventurers they bump into is Jack London. Knowles characterizes him as an arrogant, drunken lout who beat his sled dogs unmercifully. Pathetically, this sort of terrible behavior was not atypical. Many of these miners either out of ignorance, frustration, or just, sheer meanness, took out their frustrations on these sled dogs. This brutal treatment pained her greatly: “the mushers would whip and slash the poor beasts until their cries made me ill.”

These desperate camps come to life beneath her thoughtful gaze. Her observations make us aware of how much social mores have changed in the last 100 years. At one point, describing the women who frequent these almost exclusively male locales, she reveals her 19th century bias by classifying them as “low women … mostly of the chic Frenchy type… the worst sort. One thing that stamped these women as bad was not so much the foul language they incessantly used but the gum they incessantly chewed. At the time, a good woman did not chew gum.” From that whimsical description she turns her attention to another sad facet of these camps – suicide. “A light was shining in the cabin where the young couple lived…the door was pushed in and disclosed the young man and woman lying dead on the floor. A revolver was clasped tightly in the man’s hand… the reason for this apparent suicide pact was only divulged when the contents of the room were examined. They were found penniless and without a thing to eat… When they had run out of supplies, they were probably too proud to ask for food, and as the young man could find no work or means of finding assistance, the two decided the easiest way out was death.”

During their stay in the Klondike deadly typhus fever broke out. Ignoring the potential danger to herself, she visits the ill men in their cabins and tents, tending to them as best she could. She never acknowledged that her actions were brave and courageous, simply noted the men’s need for gentle care and compassion.

Later, she contracted the fever and though she became quite ill, her reflection is not morose, but matter of fact, humorous even, recounting how she surreptitiously drank as much water as possible, which evidently, was risky behavior for a typhoid patient.

What most affected Knowles were the incredible hardships endured by all in these dystopian settlements. So many had sacrificed so much to succeed in the Klondike — hoping beyond hopes — to strike it rich, bring wealth back to their families in the “Outside.” A few did hit the motherlode and returned heroes to their loved ones. Others struck it rich only to lose everything at the gaming tables — tragically, after years of struggle, reduced to nothing. And then, there were those men who endeavored valiantly and turned up empty-handed. Yet, despite all of its ugly, mean, cold and inhospitable ways she brings an enlightening perspective to this vexing expedition to Canada’s far north. She manages to discern a caring side in some of these wayward travelers, whose spirits were tested beyond belief, in their mad pursuit of that sly, seductive temptress — gold.

Knowles saw all of this, reported it and amazingly, did not grow bitter or become disenchanted with these men’s weaknesses. She chose to concentrate on their inherent goodness and that belief in humankind gave her the grace to weather the travails of the Klondike.

*Note: This book is available only for pre-order until its release on June 15.

• David Fox is a freelance writer who resides in Anchorage. Contact him at dfox@gci.com.