The day was Sept. 11, 2001.

While my mom and I stared in horrified disbelief at the live footage of a jetliner crashing into a World Trade Center tower on the other side of the continent, my dad was on his way to meet Forest Service personnel to harvest trees on my “self use” permit in order to begin building my floathouse.

As the order went out to shut down all Federal travel, a USFS skiff out in the middle of the vast Tongass National Forest continued on its way to rendezvous with my dad. They told him since they had no way to contact him and they knew he’d be waiting for them, they made the decision to work around the order. This was my introduction to building a floathouse, from the logs up, in the Southeast Alaskan bush.

First we assembled the huge float logs and cumalonged the brow logs onto them to hold the float together. I bribed my older brother Jamie with venison meat pies to sledgehammer in the 3 – 3 1/2 foot long steel pins salvaged from a nearby shipwreck.

Once we had the float together, my dad borrowed a chainsaw mill and sawed round logs (each weighing about a ton) into square “sled” beams that we built the foundation of the house on. The sled makes it possible for me to slide my house onto shore if the need should arise.

My dad milled every piece of lumber in his mobile sawmill while I hauled away the sawdust, and then we hauled the boards through the woods to my float. Other times we bundled the lumber together and when the tide came in we towed it behind the skiff. One bundle got away from us and threatened to crash into the rocks and come apart.

As I leaped out of the skiff with the pike pole, to catch it before it could self-destruct, I slipped, fell, and my right thumb went into a crack in my parents’ dock with my full weight landing on it. I jumped up, still focused on the bundle, and managed to grab it with the pike pole before it wrecked. I got on it and poled it around to the float, but by the time I was done, it was obvious my thumb was broken. My mom splinted it and I learned how to hammer nails without using my thumb.

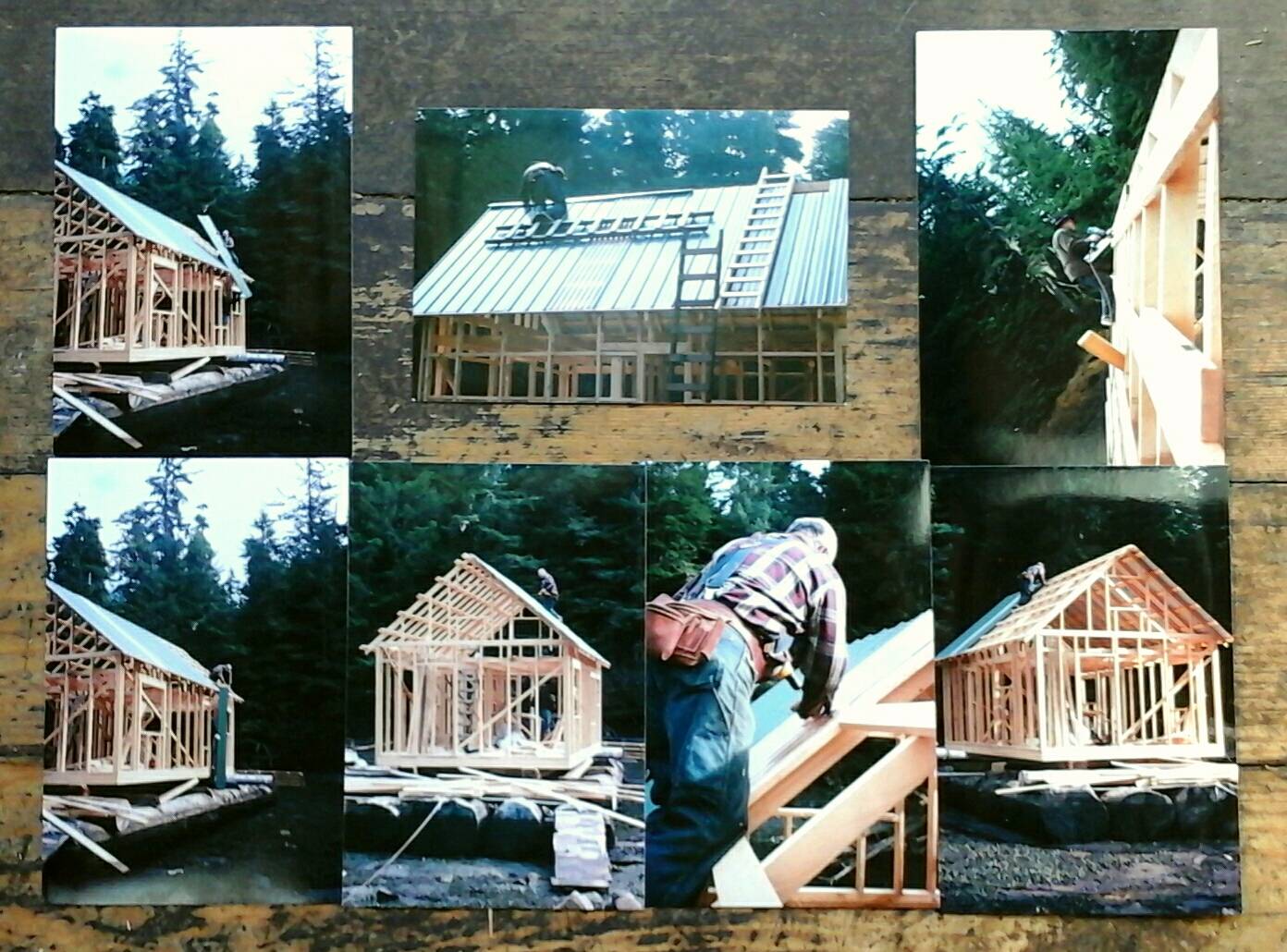

We put the foundation down in the dead of winter, hiding the skill saw in a five gallon bucket to protect it from snow flurries as we sawed and hammered. My dad and I pushed up the wall frames, each weighing 500-600 pounds (wet), and nailed them into place. We used galvanized nails because of our severe winter storms — galvanized nails grip better. (My dad, who had done some construction work in Florida, noted that they didn’t used galvanized nails there, which might help explain why their houses are more prone to high wind damage than ours).

In the spring we put the roofing on. An older neighbor who stopped by as we were working couldn’t stand being left out, so he took over lifting the steel sheets up to my dad who screwed them in place.

During the summer I hauled more lumber and nailed in the fire stop blocking between the wall studs. Instead of full thickness two-by-fours for the framing, my dad had decided to go with two-by-three spruce for the sake of saving on weight, always a consideration with floathouses. We put tar paper up on the outside of the walls and then my dad and I nailed up the cedar siding, standing on overturned five gallon buckets to reach the tops of the boards.

In the fall, we got a terrible phone call. My second youngest brother Robin wrecked his car in Ketchikan. Among other injuries, almost every rib was broken, one foot and leg were shattered and he had severe head trauma and blood loss.

Robin had to be immediately flown to the trauma center in Seattle by Lear jet and my Uncle Lance accompanied him. The next morning a local floatplane company, Pacific Air, generously flew my parents free of charge into Ketchikan first thing in the morning so they could catch a jet South.

While Robin was in the ICU, Jamie came out and together we worked on putting tar paper on my interior walls, telling each other that Robin would make it — through sheer stubbornness, if nothing else. He was easily the most stubborn person we’d ever known.

At night, on my own, after Jamie returned to his home in the village, I climbed onto the scaffolding above the front door where the porch would go, and looked up at the stars mirrored by the phosphorous in the water my house floated on. I felt disconnected from the world, as if my floathouse was floating in space. I’d think about my parents so far out of their element at Robin’s side in the hospital, and prayed they would be all right and Robin would make it.

After harrowing setbacks, he finally did, and my parents were able to return home. During winter, spring, and summer I worked on the interior of the house. I stood for hours, covered in fine sawdust, as I sanded every board that would go in my floor. My dad had jobs that took him to Ketchikan so I learned how to use the chop saw and other power tools to put up the bathroom’s interior walls and trim (though I used a hand plane on some of the trim work). I was using the skill saw when my mom came over and told me I’d have to down my tools.

My 13-year-old nephew Erik, who was staying with us, had just chopped off the tip of his thumb with a hatchet. It was the middle of the summer tourist season and every floatplane was booked solid, they couldn’t send one out to pick him up and take him to the hospital. Instead, Dan Pack, a neighbor with a tourist lodge in Meyers Chuck, offered the use of his 18-foot welded-aluminum skiff with a 90 hp outboard on the stern. All he asked was that I refill the tank and get the skiff back to him that evening since he had a sighsteeing trip early the next day.

It was a rough 35-mile ride in, and we constantly took water over the bow. Erik cradled his heavily bandaged thumb and threw me scared looks. It was a relief when we made it to the loading zone at a dock in Ketchikan that was within walking distance of the hospital. My mom had contacted my dad and he was at the hospital to meet us.

I handed Erik over to him and ran back to the skiff, hoping to get to the fuel station before it closed. I didn’t make it in time, but a kind local who was fueling up let me use his card that gave access to the pumps after closing hours. I paid him cash and took off up Tongass Narrows as sunset color streaked the sky.

It was a smoother ride going back and I got lost in the beauty of Southeast Alaska, with the mountain ranges of Prince of Wales Island on one side and forested, sheer rock bluffs on the other. And my new home, a floathouse I’d built with my own hands, was up there in the distance, amidst in all of that wilderness.

Tara Neilson is a columnist for the Capital City Weekly. She also blogs at www.alaskaforreal.com.