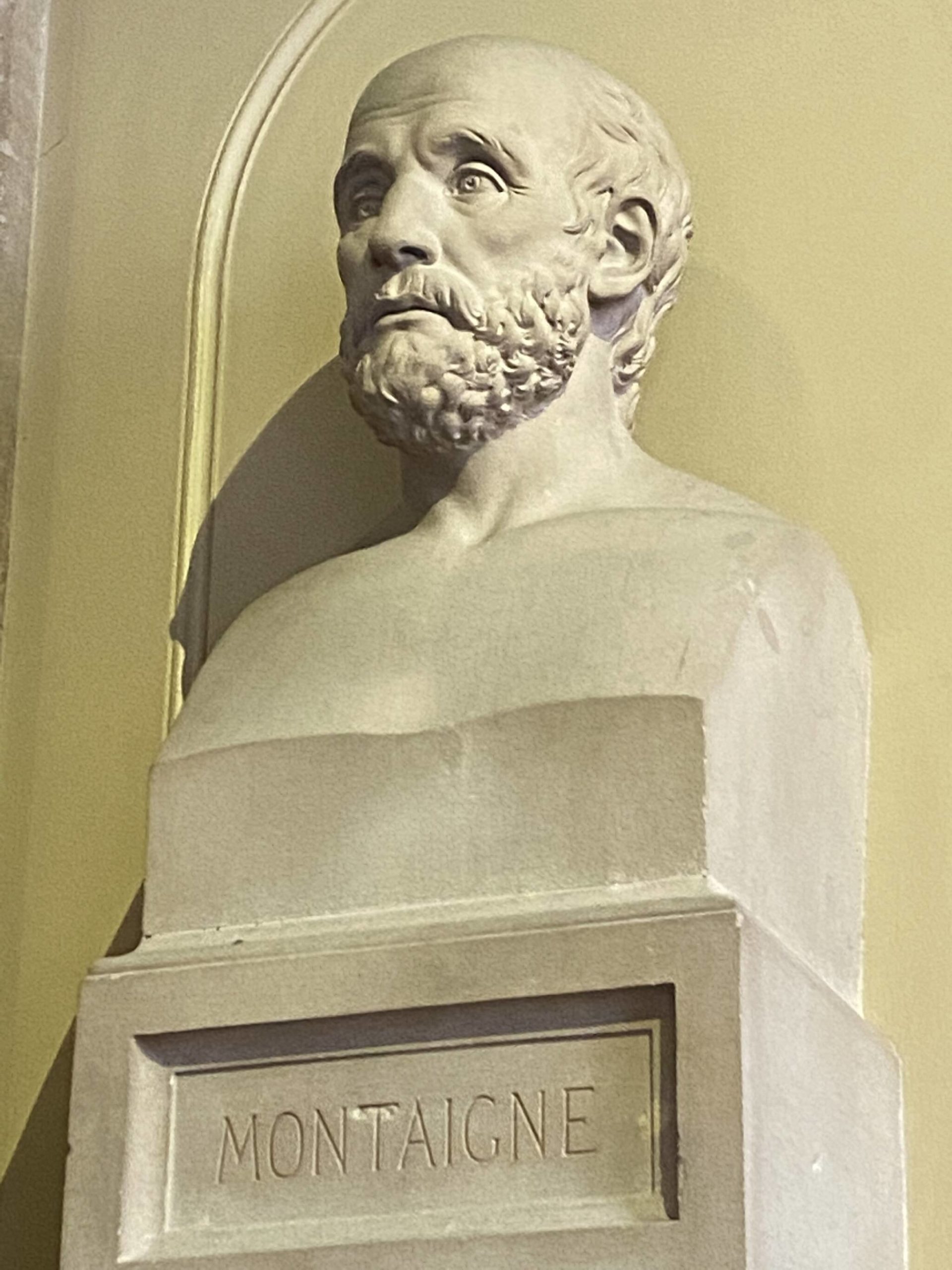

“Mon metier, mon art, c’est vivre.”

(“Living is my profession and my art”)

—Michel de Montaigne

In memory of Sol Neely

Philosophy is biography, nothing more. It’s not some abstract theory about metaphysics or ethics or aesthetics, and it’s not some systematic intellectual framework. We make philosophy with our lives, or we don’t.

The college mentor who has meant the most to me over the 40-plus years since I studied with him was a professor named Anthony Padovano, who I have mentioned before in these pages, a world-renowned theologian and, before I met him, a Catholic priest and the director of the Immaculate Conception Seminary in New Jersey, the seminary attached to Seton Hall University.

Padovano’s theology changed his life.

It led him to question those rules of the priesthood that deliberately place the clergy apart from and above their congregations, the regular women and men whom the clerical vocation is meant to serve—as if the clergy were more godly, more pious, more better.

Padovano’s theology ultimately made him doubt the spiritual value of things like the Catholic clergy’s faux heroic posture of celibacy — something that we all know now is indeed largely just a posture. These ideas led him to question any of the ways we separate ourselves as different from everyone else.

Having abjured those aspects of the priesthood that separate the clergy from common humanity, Padovano had something happen to him that happens commonly to men and women.

He fell in love.

It cost him his priestly vocation. But it gained him a partner and a family.

Padovano’s theology changed his life. And it changed mine.

What impressed me most about Padovano was that I could see his theology reflected in his life. All of my professors had big ideas about life and literature and poetry and philosophy, but Padovano lived his big ideas; he lived his theology, which was rooted firmly in how to behave like a human being.

I was intent on living my inner life before I studied with Padovano. Having joined the Navy at 18 to avoid being drafted into the Army, I still could not reconcile military service with my opposition to the Vietnam War, which was still going on at the time. I sought a discharge on grounds of conscientious objection. Six months and some 75 pages and innumerable legal hearings later, I received my Honorable Discharge as a Conscientious Objector.

I say I was intent on living my inner life, but that kind of misstates the case. I simply didn’t know any other way to be.

When I got to college after getting out of the Navy, I discovered in Professor Padovano an example of how to do it. He too seemed intent on living his inner life. I became a fan. And I became his student. And I learned a thing or two that stuck with me, ideas that I am still trying to live.

In these columns and in my life I am looking for the freedom to expose and explore those aspects of my character that our culture defines and often derides as feminine, as effeminate — a softness, a tenderness of heart, a more robust emotional life, sewing.

It’s a quest for a creative personal aesthetic that has nothing to do with wanting to be a woman; it’s my wanting to be free. That’s the transition I am trying to effect: to live my inner life, to make my life my philosophy, to live the way I see things, and to do it in a way that matters to others.

Philosophy is biography, nothing more. We make philosophy out of our lives, the way we choose to live, the way we act — deliberately, consciously, purposefully.

I can’t imagine any other way.