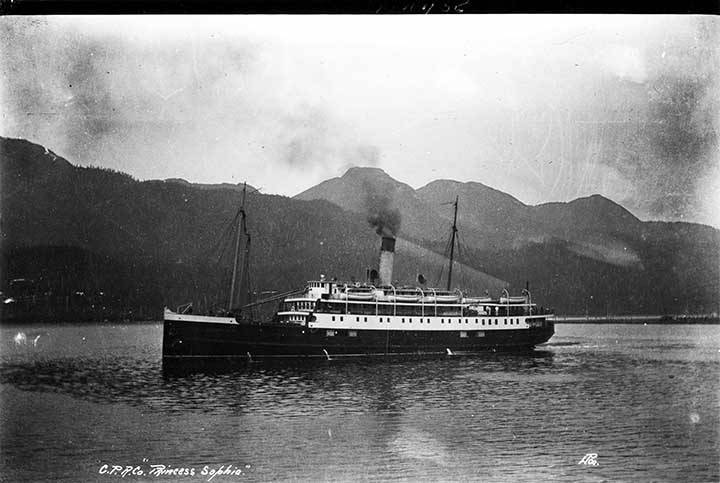

On Oct. 24, 1918, the S.S. Princess Sophia, a coastal passenger liner in the fleet of the Canadian Pacific Railway, grounded on Vanderbilt Reef in Lynn Canal. Rescue boats were unable to come to the aid of the passengers due to extreme weather conditions. On the next day, the ship sank, taking all 353 people with her. Only a dog made it to shore.

This harrowing piece of Southeast Alaska history marks the deadliest maritime disaster along the Pacific seaboard of North America, though the story is not widely known. Coming up on the 100th anniversary of the sinking in 2018, the Orpheus Project plans to bring new awareness to her story through an opera commissioned through writer Dave Hunsaker and composer Emerson Eads. The Amalga Chamber Orchestra, which conductor Todd Hunt referred to as the Orpheus Project’s residential ensemble, will accompany vocal soloists to perform selections from both acts of the opera for its “Southeast and Beyond” concert as a teaser for the opera’s premiere.

“There’s a huge cast of characters,” Hunt said. Well known figures died when the ship sank — Walter Harper, the first to reach the summit of Mount Denali, or Lulu Mae Eads, the subject of the Robert Service poem “The Shooting of Dan McGrew. “There are a few islands … of people, the main one being the folks on the Sophia …the other part of the drama are the folks on the rescue boat who are there and want to help but can’t get to them. With the wireless operator they are able to communicate. …It’s going to be our biggest budget show of all time,” he said.

The libretto

Hunsaker, a playwright and screenwriter who splits his time between California and his home in Juneau, was approached by Hunt about finding someone who could write a libretto for an opera on the Princess Sophia. Hunsaker responded “Yes, me.”

“I’ve been fascinated by this story for a long time,” Hunsaker said. His friend Dan Fruits created a series of paintings of the Princess Sophia for an art show (which will also be projected as a backdrop for the opera). The paintings struck him. The two read letters penned by the deceased passengers while they were grounded on Vanderbilt Reef and which were later recovered from the wreck at the opening of the show, Hunt said, calling them “interesting and poignant.”

Hunsaker lives on Lynn Canal, not far from where the wreck happened and right where the dog came ashore, he said. He knows the area well and has seen the water white-capping and forbidding, like the day the Princess Sophia ran aground.

Hunsaker has written musical theatre pieces before, but this was his first opera.

“(Hunt) said we’d love for you to write the libretto, and I had to go look that up,” Hunsaker said with laugh. (A libretto is the text of an opera). He took himself on a crash course on modern opera, taking recommendations from Hunt, Fruits, who is a fan of opera, and Eads, who was commissioned to write the music for the opera.

“I was kind of alarmed at how non-melodic a lot of (operas) were. Some of them I found to be quite dissonant and jarring,” Hunsaker said. “I was really quite thrilled to hear the first music (Eads) had been composing for this, because it’s very melodic and soulful and grand and tragic and all the things this story is.”

He lifted lines from the letters for some of the text, which fit well to music, he said. He also phrased lines based on characters’ histories. For a missionary couple, for example, the words read like a hymn, and for Lulu Mae Eads he wrote in verse like Service’s. He aimed to also include those that died who weren’t famous. He wrote the names of every single person — all 353 people who died — into the opera to be read like a litany.

“When you see those numbers, they’re kind of just numbers. I think that’s one of the reasons why the Vietnam Memorial in Washington D.C. is so powerful, because it’s everybody’s name,” he said. “Somehow all those people, the crew and the passengers, the Chinese guys who worked below deck, all those people somehow belonged in (the opera).”

The sinking of the Princess Sophia was overshadowed by other shipping tragedies, namely the RMS Titanic in 1912, which struck an iceberg, and the RMS Lusitania in 1915, which was torpedoed by a German U-boat. At the time the world’s gaze was also drawn to “the war to end all wars,” which racked up a death toll of about 37 million civilians and members of the military. The Spanish Influenza, one of the deadliest epidemics in recorded history, killed between 20-40 million people around the same time period, too.

Hunsaker said after the bodies had been collected from the Princess Sophia, and after they made a stop in Juneau, the Sophia’s sister ship took the bodies on to Vancouver, where the Sophia was originally bound. It made port on Nov. 11, 1918, the armistice of World War I.

“All the bells were ringing and people were hugging and crying and dancing, literally dancing in the streets, and they didn’t want to hear about more death,” Hunsaker said was one of the reasons he thinks the Princess Sophia’s story still remains largely unknown. He wasn’t even introduced to the story until Fruits told him about it.

“It remains the biggest shipping tragedy on the west coast of North America. I think that we remember it in Juneau because it happened in Juneau. The people had to deal with the bodies in places that are now the Hangar; the Merchants Wharf was turned into a morgue. High school kids came and helped clean up the bodies … all the bodies were covered in bunker oil because the ship’s boilers exploded when they hit the cold water,” Hunsakers said, stating there were feelings of bitterness and regret from Juneau people who thought they should have been able to save the people who died.

Besides writing the play, Hunsaker will be the stage director too. He has directed his own plays before, so this will not be new for him. It makes sense for him to handle stage direction, since to make the script, he had to see it visually, he said.

“I was trying to imagine how can we have (353) people sail under the stage somehow. I couldn’t think to do that in any literal way that wouldn’t be silly or cost a tremendous amount of money. Even if we could do it, we saw Titanic; we’re not going to replicate that on stage,” he said.

Inspired by Juneau Dance Theater and the work of artistic director Zach Hench, Hunsaker has envisioned the Princess Sophia as a young female dancer, with the sea and wind played by other dancers. Having the ship played by a young woman seemed fitting, Hunsaker said, since the Sophia had been young, completed in 1912 and had state of the art staterooms and woodwork.

The official premiere date is not yet set. They’ll be tweaking the opera and its music as needed, but it’s already well on its way.

“It’s been a really interesting experience so far and I’m looking forward to the next part, which will be bringing (the opera) to life,” he said.

The music

Once the libretto was finished, Emerson Eads composed the music for the opera in a six and a half month period, wrapping up in July 2017.

“It took a while to develop a … sound palette. So you have different characters and you try to figure out how to express them musically and try to think of voice types, what they would be like, how they would sound. Then I tried to find an overall musical palette for the entire thing and how it’s going to sound. Is it scary? Psychological? Is it largely epic and historic? That’s what I settled on, an epic sound, big orchestra, big choir, and big things for each of the singers. It really aims to express the tragedy and the heroism that was revealed in the incident,” Eads said.

The litany of names Hunsaker wrote in “initially horrified” Eads, as he was unsure how he would weave them into the fabric of the music, but said he eventually came to love their inclusion.

“So what it required of me was first to be able to pronounce the names of each person, but then find a musical motif that could carry that name. It ended up being a very moving experience for me just to have to physically put my mouth around those names, and then the profundity of the disaster really started to hit me… (fitting in the names) was a really daunting task. … As part of the musical fabric, each name is spoken. … I think that feature of the libretto was (an) unexpected genius thing from (Hunsaker).”

One of the people who died, Lulu Mae Eads, shared a surname with him. He found “some poetry in that part of it,” he said.

“The Southeast and Beyond” concert is Saturday, Nov. 11 at 8 p.m. and Sunday, Nov. 12 at 3 p.m. at Northern Light United Church. Tickets are $5 for students, $15 for seniors and $20 for general admission. The music from the opera will consist of selections from both the first and second act, totaling between 17-25 minutes. Other music at the concert will be Juneau composer Artemio Sandoval’s “Fortress of the Bear” and Alan Hovhaness’ “Symphony No. 52, ‘Journey to Vega.’ Op. 372.”

• Clara Miller is the staff writer for the Capital City Weekly. She can be reached at clara.miller@capweek.com.