From Empire columnist Bjorn Dihle:

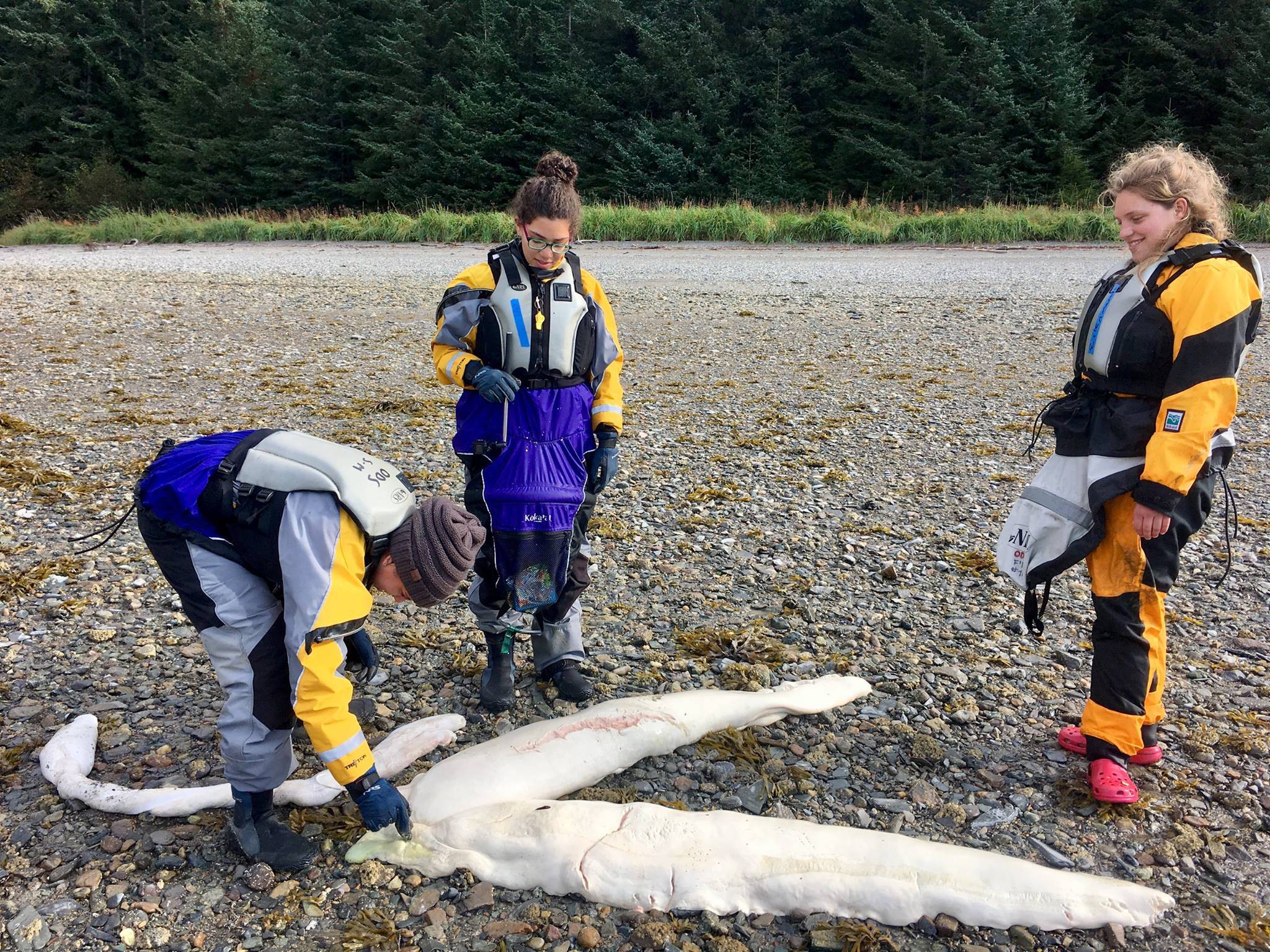

Two weekends ago my kayak class made an interesting find washed up on a beach during an outing to Berners Bay. Perhaps someone with experience with large marine animals might have guess what this is? I was in Berners Bay this weekend and visited the same beach but, of course, the tide had washed whatever it was away. My best guess would be some kind of internal organ.

Theories flew when Dihle posted this picture to Facebook on Oct. 9. Could this be from a giant squid? A shark? I have my fingers crossed for a kraken.

Experts say that, without a tissue sample, it would be hard to be 100 percent certain what this is. A good place to start would be what this probably isn’t: the sperm sack from a 400-pound king salmon. Nobody is buying that fish story.

It’s also safe to rule out any kind of plant species.

This strange blob has three parts. Two flat, similar parts and a skinnier, round part that seems to have segments and a bulbous end.

Dihle, an avid hunter, said the flat parts had a “livery” consistency, so let’s explore the idea that this is an internal organ of some sort. Each of these pieces are about five feet long, so they would have to be from a large marine animal.

The find doesn’t come from a mammal, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association’s John Moran. He’s seen a lot of whale guts: Moran runs NOAA’s necropsy lab at the Ted Stevens Marine Research Institute in Juneau. He regularly cuts open dead sea lions and whales to find out how they died.

Marine mammal organs look “pretty much like ours,” Moran said — only, of course, much larger.

“I don’t think it is mammalian, my first guess would be testis or liver from a sleeper shark. … Second guess would be something internal from a squid, but it seems a bit large for the squid I’ve seen wash up around here,” Moran wrote in an email.

This links with several guesses from commenters on Dihle’s Facebook post, who suggested it could be from a shark. Moran thought they were onto something, so he emailed his NOAA colleague Cindy Tribuzio.

Tribuzio does shark stock assessments for NOAA. She just got back from giving a talk on sharks in Alaska at the New England Aquarium in Boston as part of The Gills Club Symposium hosted by the Atlantic White Shark Conservancy (You can see a video of her talk on Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T1XNpkW0q7Y).

There are three sharks this could possibly be from: the Pacific sleeper shark, the spiny dogfish and the salmon shark. Because of the shape, Tribuzio said, it’s likely from a sleeper shark.

“Sharks have very, very large livers; it fills up most of their abdominal cavity,” Tribuzio said. “It looks like the right shape for a sleeper shark. They tend to have a longer, pointier liver, as opposed to a salmon shark, which tends to have more of a rounded liver.”

Tribuzio is pretty certain the two flat parts are a Pacific sleeper shark liver. But that leaves the third, rounded part, attached to the liver by a thin strand of connective tissue.

Though Tribuzio said she recognized the flat parts as a shark liver almost immediately, the third part is much less obvious.

“I really am hesitant to make any claims on this one. But just by looking at it, I would guess it’s part of a reproductive tract. It could even be, less likely, it could be part of the stomach that’s been really contracted,” she said.

Given the size of the liver, it was probably an immature animal, she said, adding that she wouldn’t expect the reproductive tract of an animal this size to be so developed. Sleeper sharks can grow to around 14 feet. Tribuzio estimates this one was 7 to 10 feet long.

But why did it wash up on the beach intact? Livers tear easily, Tribuzio said, and it’s unlikely it would wash up on the beach in one piece if it was killed by a predator.

The liver is also the most nutritionally dense part of the shark. The meat on a sleeper shark is toxic, while the liver isn’t, so it’s odd that nothing ate before it made it to the beach.

Sleeper sharks are the most abundant species of shark in the Juneau area, Tribuzio said, but it’s very hard to say how many of them are milling around. They’re a “data-poor” species.

“Because of its size, it’s pretty hard to bring on board. They’re also pretty soft,” she said. “Most of the catch comes from hook and line fisheries and those are usually smaller boats. They can’t deal with a 10-foot shark.”

Interested in learning more about sharks? Join the Gills Club at gillsclub.org. Tribuzio said she’s trying to get more Alaskans involved.

• Curious by Nature answers reader-submitted questions about Mother Nature in Juneau and Southeast Alaska. Ever wonder why Juneau’s water get so much murkier in the summer? Just how fast is the Mendenhall Glacier melting? Is the Fukushima disaster hurting Juneau’s salmon stocks? Why your dog loves the smell of bear poop? Submit your question to outdoors@juneauempire.com and we will scour mountains, rivers, labs and university hallways to try to find the answer. You can also contact reporter Kevin Gullufsen directly at 523-2228 or kevin.gullufsen@juneauempire.com.