It goes without saying that I’m accustomed to having the wilderness entirely to myself. Which was why I was surprised one summer morning when I looked up from beachcombing in a nearby bay to find four naked men sunning themselves in front of me.

They looked at least as surprised as I was to find, in what they’d thought was a secluded, uninhabited Alaskan bay, a woman strolling along the rocks towards them.

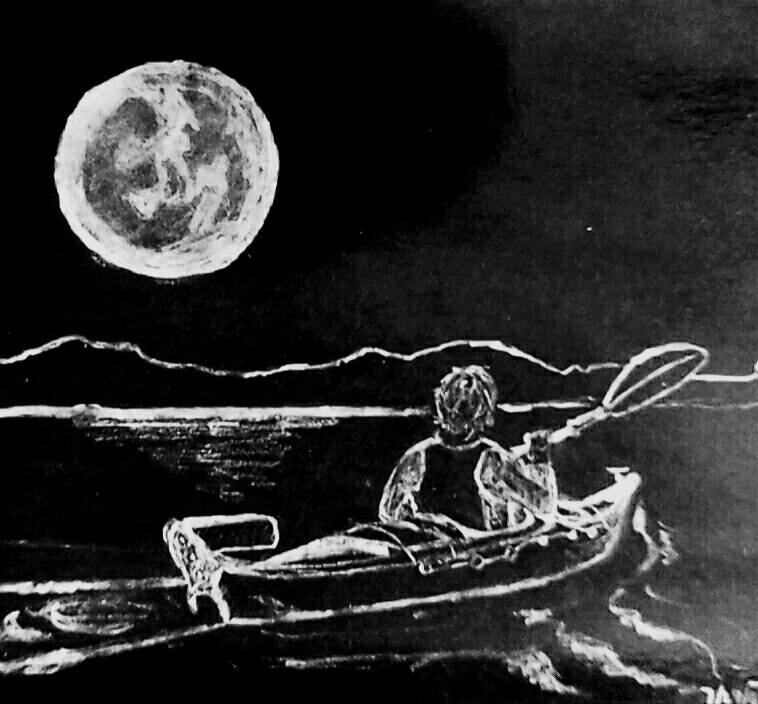

As it turned out, they were kayakers from the Lower 48 who’d had a tough morning battling the unpredictable seas of Clarence Strait and thought the best way to dry out was to spread all their possessions, including the clothes they were wearing, on the nearest beach the sun shone on.

I said a polite hello, explained where I was from, and told them if they needed anything they could call on us, and turned away to continue my beachcombing expedition in the opposite direction.

Later that evening one of them did come calling, asking if we could direct him to a reliable freshwater source. I told him how to get to our dam, and we chatted for a while about him and his group, their goals, backgrounds, and his girlfriend troubles (she didn’t like him going on this trip).

Most of the kayakers we see are in their twenties, with few relationship attachments to worry about, on a once-in-a-lifetime adventure to Alaska. Like the lone kayaker from Quebec named Eric who stopped in at my parents’ floathouse. They invited him in and shared some refreshments with him. I could only say a brief hello because, I explained, I was packing to leave on a trip to Anchorage.

He nodded agreeably, chatting about his journey with a strong French accent, and proceeded to strip down in front of me. Hmmm, I thought, this must be how they do things in Quebec. I offered him a towel.

I returned to my own floathouse, dealing with laundry I’d hung on a clothesline inside my house back in the days before we had the glorious luxury of a propane dryer. The next thing I knew the kayaker had opened my front door and was taking pictures.

Really? I was accustomed to tourists thinking that the locals and their homes were part of their vacation package, but this seemed a bit much.

Eric was a good looking, good-natured, extroverted guy who was apparently unused to being denied anything. After parrying a few of his questions, I politely repeated that I really had to pack. He finally took the hint and returned to my parents’ house. After asking for their address, and promising to send photos of his trip after he returned home, he continued on his journey. Several months later he followed through and sent photos of his adventure.

Another French kayaker, this one from the country of France, stopped in on his ambitious plan to circumnavigate the world by kayak, dogsled, and bike. He was fascinated, he told us, by how many words there are to describe a body of water in our language: bay, strait, passage, sound, harbor, cove, inlet, lagoon, bight. He was thrilled, and immediately jotted it down in his water-stained notebook, when we told him about “chuck.” We never heard from him again, so we never found out if he did manage to circle the globe.

Meanwhile, in nearby Meyers Chuck, a young couple my age had bought my grandparents’ house and had turned it into a kayak lodge. Dan took the guests on kayaking trips to the islands across from where I lived, while Kerri acted as cook and hostess. They’d had a little girl the year before and needed a live-in nanny and asked me to take on the job. I’d live at their attached, one-room, unfinished cabin with the toddler, Hadley, for the duration of each trip, and returned home between groups.

The kayakers who came to the lodge were much different than the loners we’d get stopping in at our floathouses. Most of them were older, or a family group. I spent most of my time with Hadley, but when I did interact with them, they pumped me eagerly for details on growing up in the wilderness. I felt like I was on a par with the bears and whales they were looking forward to taking pictures of.

A few years later, while my dad and I had a job putting in telephone wire, we pulled up onto a beach where colorful kayakers were spread out, some sunning themselves on the remains of a shipwreck.

They stared at us in blank disbelief as I jumped out, packing a .44 on my hip (we’d sighted bears earlier). Kayakers are always surprised to find other humans wandering about the wilderness, let alone ones who were hauling telephone wire into the woods. They thought it was a joke. How could there be landline telephones when all you could see in any direction was forest and ocean?

They were a retirement group who’d apparently long cherished the ambition to live a wild and edge-of-the-known-world experience to regale their friends with when they returned home. Our matter-of-fact, telephone-wire laying chore sort of deflated the wilderness aspect of it all. They pointedly ignored us as we went about our business.

Then there was the Australian couple — his accent was so thick she had to act as interpreter; the young guy from Bremerton, Washington, who announced with just pride that he’d built his glossy, wooden kayak himself; the woman in her seventies who paddled up from Hawaii every year (Audrey Sutherland, you can find her books on Amazon and elsewhere).

Every summer we see kayakers paddling past, or occasionally they’ll stop in when they see our floathouses. Sometimes when I go to pump water I’ll see one of them setting up a tent near our dam on the remains of yet another shipwreck. We do, after all, live on a main Southeast Alaskan thoroughfare and kayakers are the long distance bicyclers of marine traffic.

I wonder in what other life do you get people, perfect strangers, coming and visiting you at your home to share their life stories and adventures?

Tara Neilson is a columnist for Capital City Weekly and blogs at www.alaskaforreal.com.