The Tlingit language is such an elaborate language.

It needs to be lived: It is a living language — Vivian Mork Yéilk’

I was afraid. I sat down in the small chair, my knees bent upward. I set a few stuffed animals, a set of color cards, and a cheat sheet on the round table in front of me. I cleared my throat. Four kindergarteners stared at me, waiting. I didn’t realize it then but I was embarking on a life-changing journey.

My children’s ancestral homeland is Glacier Bay, and the nearby village of Hoonah is filled with their relatives. They were born of place and language; Born of Táx’ (Snail) and Yéil (Raven) of Xuniyaa (Hoonah) of Lingít Aaní. Their identity is a social relationship to the landscape; therefore, learning my children’s ancestral language would deepen relationships with them, their relatives, and to the land. As a family, we could learn the language together.

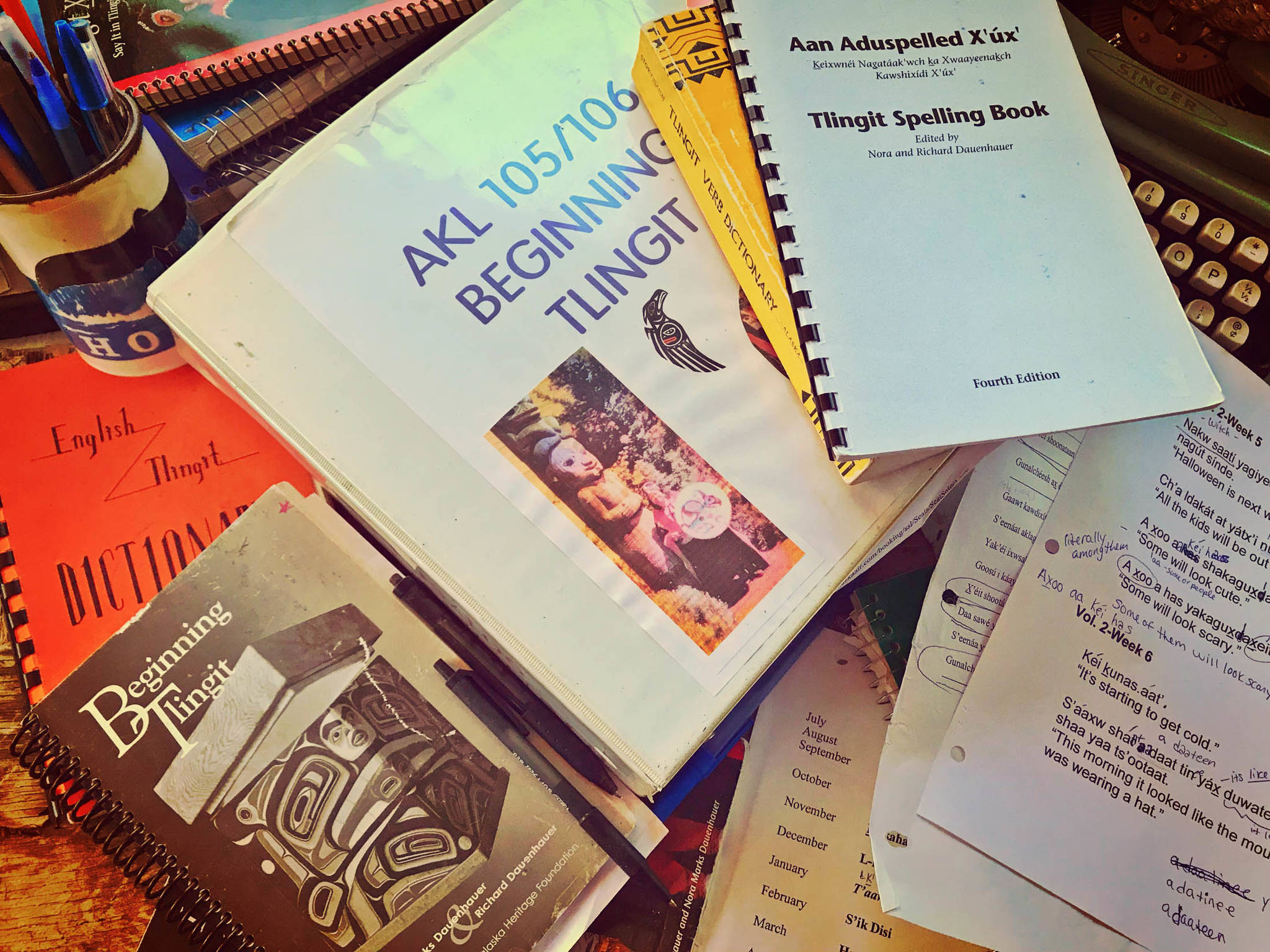

It was my last year of undergraduate school at the University of Alaska Southeast (UAS) and I needed a full year of language to fulfill my requirements. I had arranged with the Hoonah City Schools Tlingit language teacher, Daphne K’ashkgé (Duffy) Wright, to take her class along with two high school students. Several days before class started, Daphne had given me a copy of “Beginning Tlingit” by Richard Xwaayeená and Nora Keixwnéi Dauenhauer. The first lesson was repetition drills. I put in the CD. Richard (Dick) and Nora explained the lessons in English and then began: Tás áyá. This is thread. These unfamiliar words with their high and low tones combined with hard sounds, formed sound waves that traveled into my auditory canal. The waves struck my eardrum, vibrating my ear bones, sending vibrations to my inner ear, creating electrical impulses that moved in split seconds along a nerve into my brain. It was like magic. There, my brain absorbed the beautiful strangeness of this new language. Tás áyá. This is thread. And then I cried.

I cried happy tears knowing it was possible to learn. I’d heard stories about elders being punished for speaking their language. In my ignorance I’d assumed the language was dead. The lesson continued: kées, séek, gút, dáanaa, and so on (bracelet, belt, dime, dollar). I could do this. After all, I had the book, CDs, and I was about to take a class. I wiped my eyes, then closed them and listened. After the second lesson, though, I shut the player off. I flipped through the book. What had I gotten myself into? I was not a natural language learner. I’d dropped out of high school in 10th grade and received my GED. I’d never had any interest in learning another language. Could I really do this? Maybe. What I had going for me was excitement and curiosity, but the biggest obstacle I faced was fear. I was afraid to fail; afraid to make mistakes. I was afraid I’d embarrass myself. These particular fears are barriers to learning the language and quite common. So much so that “Beginning Tlingit” devotes a section to addressing it. But, somehow, despite my fears, learning Tlingit made sense.

It was 2001 and I was a UAS distance student. At that time the only language course for distance students was Spanish. Spanish didn’t fit my Alaska Studies emphasis. I was reluctant, but then friends informed me the local school taught the Tlingit language. I decided to telephone Daphne Wright to inquire about her high school course and after explaining my interest she agreed to meet and discuss it. Eventfully, after overcoming a few obstacles, Carol Williams (Hoonah City Schools Indian Education educator/director), Daphne, and I designed a college level Tlingit language course approved by the university. The course would be challenging. Later, we learned we had essentially developed a course at the level of Intermediate Tlingit. There were things Carol and Daphne wanted me to know beyond Elementary Tlingit. They insisted. They wanted me to attend ceremonies. They wanted me to be able to pass the spelling tests in the “Tlingit Spelling Book.” They wanted me to assist with developing materials. They wanted me to understand culture, protocols, traditions, and more. They wanted me to attend and help with public school events. They wanted me to belong.

Upon arriving in the Tlingit language classroom, Daphne introduced me to the two other students, both high schoolers, and then said, “Today, in 10 minutes, we’re going into the kindergarten classroom to help them learn colors and animal names.” Uh, I thought, shouldn’t I know the words first? I hadn’t done any homework yet. Apparently, my two classmates were familiar with teaching the younger grades as this was their second year. Daphne handed me a sheet of paper with the colors on it and the corresponding Tlingit words, and one with a list of animals. We were bringing stuffed animals and color cards with us.

I followed my classmates into the kindergarten room and was directed to a table. Here goes, I thought to myself. I randomly chose a card. On my cheat sheet, next to the word for the color ‘red,’ was a letter I hadn’t seen before, an underlined X with an apostrophe, so I held up the card and pronounced what I thought the word sounded like. Tlingit is one of the most complex languages in the world with 58 letters, including about 30 sounds that are not found in English. And of those sounds, four are not found in any language in the world. I’d chosen a word beginning with one of the most difficult letters in the Tlingit alphabet.

The little boy on my right fidgeted and exclaimed, “That’s not how you say it!” My cheeks reddened.

“How do you say it?” I asked him.

“X’áan,” he said without any trouble. This was the Tlingit word for ‘red,’ which also means ‘fire.’

I repeated the word the best I could. I explained to the children I was learning just like they were. They seemed to like that. We were off to a good start. I was off to a good start. One thing leads to another, so they say, like threads connecting. That week, I papered my house with Tlingit words. I labeled my dining table, the doors, chairs, windows, everything. I taught my children. My eldest daughter, Vivian Mork Yéilk’, visited Hoonah shortly thereafter and was enthused about learning the language. She became a language teacher herself and taught many students. I wrote skits and dialogue practices for the children at Hoonah City Schools, designed coloring pages, and made up games. I published a small language book for them. I started a Tlingit language family night. It took me two years to get the letter sounds somewhat passable. I made lots of mistakes. I would be embarrassed, and sometimes, yes, afraid. But I learned. I am still learning. This is thread. Tás áyá.

*Any Tlingit spelling or grammatical mistakes are mine. The Tlingit language curriculum developed by Daphne Wright, Carol Williams, and myself are being taught at the high school level in Wrangell. The language materials continue to be used in Hoonah City Schools. You can sign up for local or distance Tlingit language classes, and other Native language classes, at the University of Alaska. Gunalchéesh Xunéi ka Yéilk’ for assistance with language details in the article.

• Wrangell writer and artist Vivian Faith Prescott writes “Planet Alaska: Sharing our Stories” with her daughter, Vivian Mork Yéilk’.