Sealaska Heritage Institute (SHI) has published a landmark book on the era of Indigenous slavery in Alaska that endured more than two decades after passage of the 13th Amendment to the federal constitution, which abolished the practice two years before Alaska became part of the United States in 1867.

The book tells the story of Sah Quah, a Haida man who embarked on a courageous quest for freedom from his Tlingit owner, and the trial that ultimately ended human bondage in 1886 in what was then known as the District of Alaska.

The book, “Sah Quah,” was researched and written by journalists Jeff Landfield and Paxson Woelber, and attorney Lee Baxter. The investigative special feature first appeared on the political news site The Alaska Landmine and was reprinted through SHI’s Box of Knowledge series.

Books on the topic are rare because the issue is still sensitive, and many Native people do not want to address it publicly, said SHI President Rosita Worl, Ph.D., who was interviewed for the piece and wrote the foreword to the book.

“Although we honor our culture, we are not proud of all aspects of our history. We cannot dismiss the reality that slavery was a part of Tlingit, Haida and Tsimshian cultures and played a critical role in their development. We have yet to honor Sah Quah for having the courage to challenge the practice of slavery and for fighting for his own freedom and that of others held in bondage,” Worl wrote.

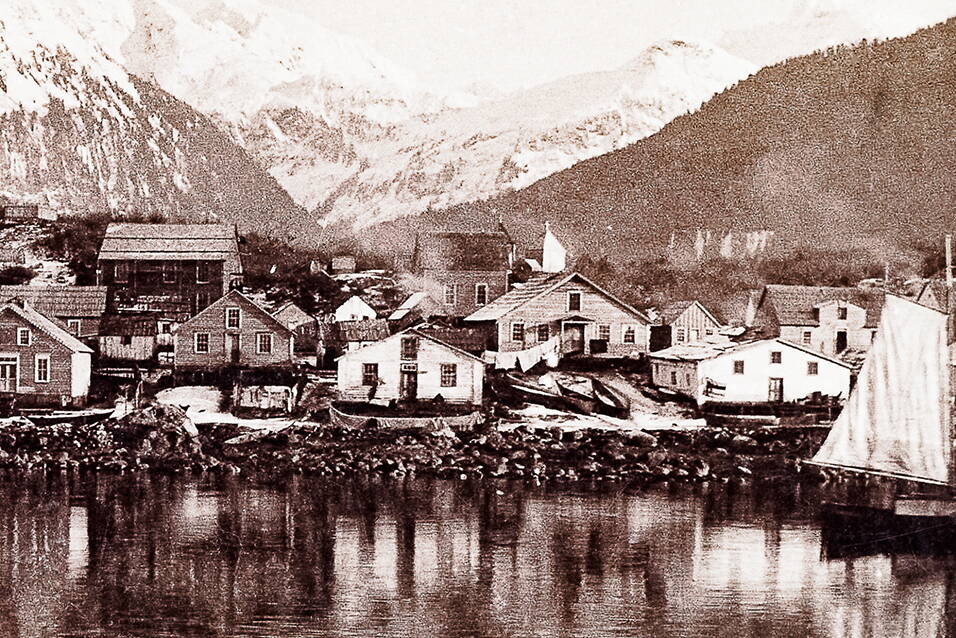

The book opens with Sah Quah entering a federal court in Sitka, alleging that he had been captured by the Flathead Indians (also called Salish) and sold into slavery as a child. Sah Quah said he was trafficked up a Northwest Coast slave-trading network and was, at the time of the trial, enslaved by a Tlingit man in Sitka named Nah-Ki-Klan. Sah Quah had come to the American court, he said, to seek “papers” freeing him from his bonds.

The book explores how slavery came to exist and persist in Alaska despite the federal act that banned it and examines the Tlingit, Haida and Tsimshian property laws that Native and some non-Native people believed preempted the United States’ constitutional edicts. The Tlingit also asserted they were a sovereign nation and not subject to the laws of the United States.

The practice of slavery was widespread in the region. Early Russian fur traders noted that many Tlingit slaves were Flathead Indians who had been enslaved and traded far up the coast. Individuals were enslaved as far north as Dena’ina territory, which encompasses the Cook Inlet region and present-day Wasilla, Palmer and Anchorage, and trafficked south to the Chugach on the Kenai Peninsula, the authors wrote.

Though reliable data is sparse, most estimates put the presence of slaves between 10% and 35% of most Northwest Coast populations.

The wealthy and complex societies developed by the Indigenous people of Southeast Alaska were due in large part to the existence of slaves, Worl said.

“To try to explain our society and the wealth we were able to accumulate you have to acknowledge that there was a slave pool that was doing a lot of that labor. As an anthropologist and as a proud Tlingit, I want to acknowledge our society, and to do that you have to acknowledge slavery,” she wrote.

The existence of slavery in Alaska came as a surprise to the authors, who are non-Native. They spent years painstakingly ferreting through various archives to unearth Sah Quah’s story and the judicial ruling that set him free.

“What started as an internet search kicked off by a meeting with Paxson Woelber (who first educated me about the Sah Quah court decision) ended as a multi-year investigation with Paxson and Jeff Landfield that took us to the National Archives, the pages of 1800s newspaper articles and obituaries from Alaska, Virginia and Missouri, and historical personal papers held by Yale University,” wrote Baxter.

Notably, the team found the original trial transcript, and the text is included in the book.

Woelber said the story of slavery in North America is incomplete without an understanding of slavery in Alaska.

“The practice of legal chattel slavery in Alaska is notable not only because it likely continued longer here than anywhere else in North America, but also because it was so distinct from the form of slavery practiced, for example, in the American South: slavery in Alaska was almost exclusively a product of Indigenous law and customs, did not have a racial component per se, and ended as part of the messy and painful process of American colonization,” Woelber wrote.

“Our investigation suggests that, taken as a whole, slavery in North America is a much more varied, nuanced and complicated topic than is widely believed.”

Landfield came to view Sah Quah as a civil rights champion with a rightful place in American history.

“Sah Quah, a slave who was subjected to a brutal life, had the courage to seek his freedom in the nascent Alaska federal court. Unfortunately, very few people have ever heard of Sah Quah,” he wrote.

“Sah Quah should be celebrated as a hero who had the fortitude to fight for his freedom against an owner who, by all accounts, could have easily had him killed.”