The prevailing narrative has it that the more than 800 people who relocated from Canada to Metlakatla, Alaska in 1887 completely rejected traditional Tsimshian ways.

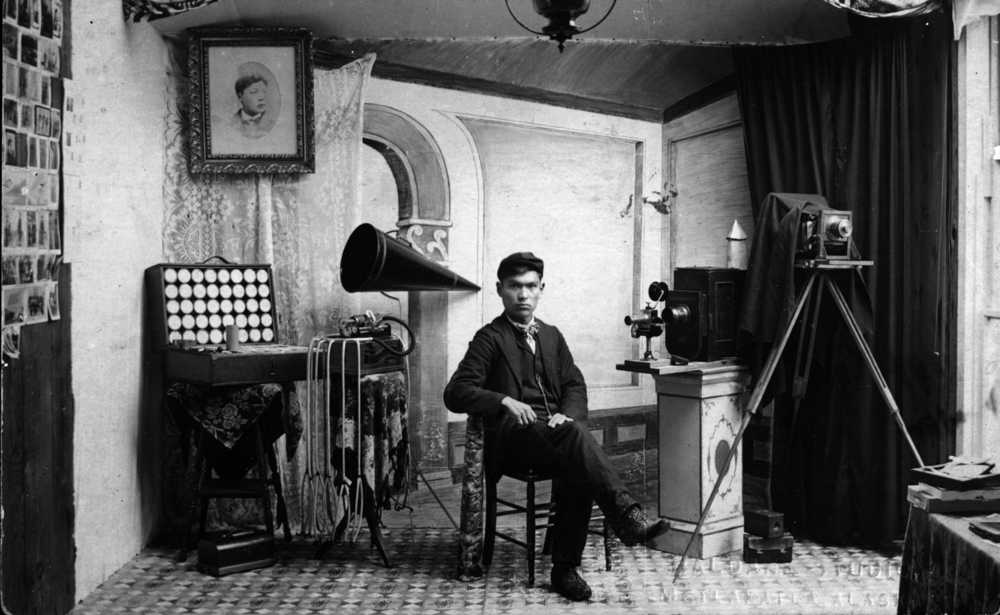

But the photographs of Benjamin Alfred Haldane, one of North America’s first professional indigenous photographers, tell a different story.

When he was 13, Haldane, who went by B.A., was one of those who traveled the 30 miles by canoe from Old Metlakatla to Alaska with Anglican missionary William Duncan. His photos present a counternarrative to the general perception of Metlakatla as “a Christian utopia” whose Tsimshian residents had rejected traditional ways of life, writes University of Alaska Southeast assistant professor of Alaska Native Studies Mique’l Dangeli. Dangeli was born and raised in Metlakatla and wrote her master’s thesis on Haldane.

“Today this depiction (Metlakatla as rejecting Tsimshian traditions and beliefs) continues to dominate our community’s representation in the written history of the Northwest Coast,” Dangeli told attendees of the 2007 Clan Conference in Sitka. That story “has overshadowed the stories of resistance and cultural continuity that persist in our community.”

Duncan expelled Haldane from school when he was 15, after he had completed third grade reading materials, saying that “there was nothing more for him to learn.”

”Like other missionaries at the time, Duncan tried to keep his Native converts at a level of education that he presumed would not threaten his authority,” Dangeli wrote in the article “Bringing to Light a Counternarrative of Our History.”

After he left school, Haldane took his education into his own hands. He taught himself music and photography from books, played the trombone, violin, cornet, piano and pipe organ, composed orchestral music, and translated Tsimshian songs to sheet music, Dangeli wrote.

He began taking family portraits at age 16, continuing while he worked at the salmon cannery for the next three years. At 25, he started his scenic and portrait photography business.

COUNTERNARRATIVE

Business was busy. Many indigenous families traveled to Metlakatla to get their portraits taken. In the prevailing photos of the time, Native Americans were usually portrayed as impoverished, and many people took the opportunity to challenge that narrative through one of Haldane’s portraits, which “emphasized respectability and wealth” in a way usually reserved for Euro-American families, Dangeli said.

Duncan created eight rules, the “Declaration of Residents,” for the people of Metlakatla to live under. Rule number five was to “never attend heathen festivals or to countenance heathen customs in other villages.” In defiance of that rule, in 1903 and 1914 Haldane traveled up the Nass River to teach music and take photographs of potlatches and other forbidden activities in the Nisga’a communities of Laxgalt’sap (now Greenville) and Gitlaxt’aamiks (now called Aiyansh).

Canada outlawed potlatching in 1884, and photos were used to prosecute people for breaking the law. But Dangeli identified eagle down on the floor in a 1914 image of Chief James Skean and his family, which indicates a ceremony or a potlatch had happened prior to the photo.

“Thus the Nisga’a people in these images and B.A. were putting themselves at considerable risk of prosecution,” Dangeli wrote. “In the sociopolitical conditions of both Canada and Alaska, the commissioning and creation of these images asserted their sovereignty by continuing to hold and witness potlatches in the face of the potlatch law and Duncan’s governance.”

In other stands against rules outlawing traditional practices and ways of life, Edward Marsden, who was Tsimshian, and Lucy Kinninook, who was Tlingit, invited guests to wear ceremonial regalia to their 1901 wedding reception in Metlakatla, an act of defiance that Haldane documented. Marsden, who in 1897 became the first Native American to receive a license to preach, would later go on to establish a Presbyterian church in Metlakatla against Duncan’s wishes.

“Taking into consideration Edward’s history of resisting Duncan’s authority, the public nature can be seen as protest against Duncan forcing people to relinquish ownership of their ceremonial possessions both upon being baptized and upon moving to Alaska,” Dangeli wrote.

In some of Haldane’s portraits, model totems, paddles, and regalia figure prominently. In one image, a young boy poses with a dance paddle and in an adult-sized button robe, which Dangeli says was likely passed down from a matrilineal uncle, as is protocol. In another, two young girls pose with a model totem that references their clan lineage.

“Considering the activities surrounding clan inheritance and protocols in Metlakatla… the composition of these two images suggests that they were commissioned for internal purposes: to be circulated throughout our community to serve the same function as bringing out crest objects at a potlatch in order to publicly validate ancestry,” Dangeli wrote.

FUTURE DISPLAY

When Dangeli began researching in 2005, only a few of Haldane’s photographs were known to remain in Metlakatla; many had been lost in house fires, thrown away unknowingly, or had been burned, according to the tradition of burning deceased loved ones’ important possessions. In 2003, Metlakatla resident Dennis Dunne saved 163 of Haldane’s glass plate negatives, taken around 1910, from Metlakatla’s waste facility. The Tongass Historical Society has ten crates of Haldane’s glass plate negatives on loan until Metlakata has its own museum and climate-controlled archive, Dangeli wrote.

There has not been a major solo exhibition of Haldane’s work, and Dangeli hopes to have one at the Alaska State Museum when her planned book comes out (the date isn’t yet set.)

“I’m prioritizing that over my dissertation,” she told the Capital City Weekly. “I feel like I owe it to his family.”

Editor’s note: All information in this article is courtesy of University of Alaska Southeast assistant professor of Alaska Native Studies Mique’l Dangeli, who was born and raised in Metlakatla and belongs to the Laxsgiik (Eagle Clan). In her articles and talks she always thanks Haldane’s family for their permission for her research, and we would like to extend the same thanks.