Do you know which bar is the oldest in Alaska?

How about what the relationship was, in the 1940s, between Juneau police and prostitutes?

Historians, museum employees, and history-philes from around Alaska gathered in Juneau at the end of September for the Museums Alaska/Alaska Historical Society annual conference. Two of those talks, by historians Doug Vandegraft and Averil Lerman, discussed fascinating, and interrelated, “hidden histories” of Southeast. Other talks — Karen Hofstad of Petersburg’s talk on salmon can labels, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park historian Karl Gurcke’s talk on the sinking of the 1898 barque Canada, now in Skagway’s Nahku Bay, and scholar Yoko Kugo’s talk about traditional Yup’ik names, among many others — focused on other aspects of Alaskan history, some more known, some less known.

“NOTORIOUS BARS”

Doug Vandegraft, author of “A Guide to the Notorious Bars of Alaska,” has traveled all over the state as a cartographer. Over the years, he kept notes on “notorious bars” — a “mixed history,” as Alaska, he pointed out, has “a long history of enjoyment and abuse of alcohol.”

Vandegraft showed historical maps of downtown Juneau’s buildings, remarkable visuals of how many were dedicated to alcohol. (In 1914, 11 bars were on Front Street, which then curved around at the Triangle Building to include what is now South Franklin Street.)

Alaska voted to go “bone-dry” two years before the rest of the country began prohibition. Officially, it was “dry” to the point, Vandegraft said, that doctors couldn’t get medicines with alcohol as an ingredient. Alaska Prohibition lasted 15 years, from 1918 to 1933.

Post-Prohibition, bars became known as dispensaries; they weren’t allowed to serve liquor until 1939, he said. The first bar to get its license was the Imperial (though the sign above the door says it opened in 1891, Vandegraft considers Prohibition as “resetting the clock.” Regardless, the Imperial still had its license five weeks after the end of Prohibition.)

Of course, Alaska was nowhere close to “bone dry” during that period.

“Bootlegging and moonshining were extremely lucrative,” Vandegraft said. So were cigar stores, card rooms and pool halls — and, presumably, so was the trade plied in the small “dwellings” the old maps show clustered around those businesses. (Territorial officials ordered an end to prostitution in Alaska in 1954, though it likely continued in Juneau until 1956. Ketchikan dealt with its “red-light district” with a big, public scandal of a trial in 1953-1954.)

“FANTASTICALLY INTERESTING” HISTORY

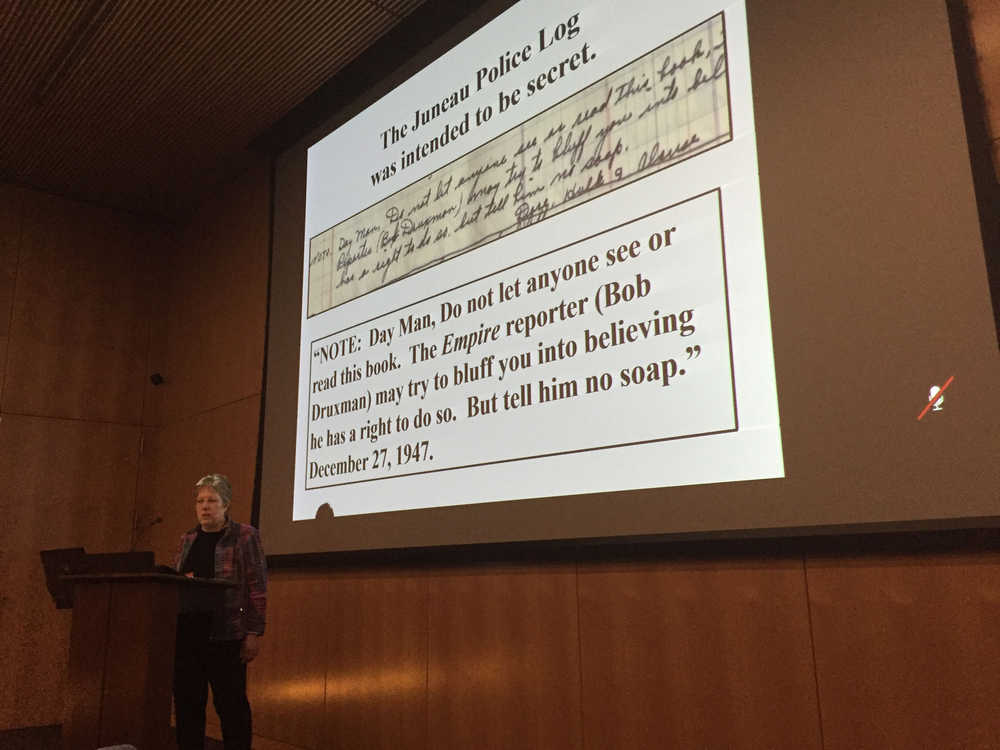

Prostitution is something historian and public defense lawyer Averil Lerman’s addressed in her talk on the “secret” police blotter kept by the Juneau police. Many of those blotters are now in public archives. Lerman spoke about the blotter from 1946 to 1947, which she said offers “a way for us to look at a mirror… of ourselves.”

Back in the 1940s, police used handwritten ledgers to communicate with each other between different shifts and record the day’s events. Federal marshals took care of felonies, and the police dealt with local eventss.

The blotter provides insights into daily life. One of the interesting aspects, Lerman said, is how many people called about missing children — toddlers that had gotten out of the house and wandered down the street, or went to sleep in a hidden corner of the house’s basement. Wives or husbands might wander away. People called about lost property: clothing wasn’t easy to get up here back then, and coats regularly went missing.

Most of the entries are “directly connected” to alcohol, Lerman said.

Police also dealt with mental health, which was a big issue; police called mental illness “going snaky” and discussed the need for a padded cell.

They regularly had to euthanize dogs and cats, disposing of their bodies through a hole in a dock, enclosed by a fence. They ensured that people diagnosed with venereal diseases got treatment (Lerman thinks Juneau had the highest rate of venereal disease in the territory.) Wives “were regularly getting seriously beaten up,” Lerman said; it was such a normal part of policing, and everyday life, that it was “almost a non-event.”

And then there’s the relationship between police and prostitutes, which Lerman said “is fantastically interesting.”

Prostitutes had to check in with the police to get permission to work, and police regulated “the line” — ensuring the curtains were drawn when the lights were on, for example, helping the IRS collect taxes from prostitutes, and serving as go-betweens with the medical clinic.

“Almost every month, the women all went to court, were fined $25 for disorderly conduct, paid, and went back to work,” Lerman said. “Were they proper court fines? Who knows.”

That 1940s census showed Juneau was 86 percent white, 10 percent Alaska Native, four percent “other” (mostly Filipino and Japanese) and .01 percent black, which translates to around a dozen people.

“Racism and racial prejudice were big issues in Alaska, as they were outside as well,” she said. “Race had a lot to do with who you were and what you could do.”

The language in the blotter was “profoundly racist,” which Lerman emphasized is not “them,” but rather “us.”

“It’s an immensely valuable record,” she said. “It shows us who we were and therefore it shows us a lot about who we are.”

“We see the same issues that we are troubled with so much now,” Lerman said at the end of her talk. “I think this is a universal human experience. I don’t think we should demonize it. I think we should accept it or at least understand it. When we understand that what we do is not what we say we do, we are at the beginning of knowing what’s actually real. And if we do know what’s real… we can decide whether we want to do it that way, or whether we want to do it differently.”

The conference was the first hosted by the Andrew P. Kashevaroff Library, Archives and Museum building since it opened in June. (Historical society talks were at the museum; museum talks were at the Sealaska Heritage Institute’s Walter Soboleff building.)

• Contact Capital City Weekly editor Mary Catharine Martin at maryc.martin@capweek.com.