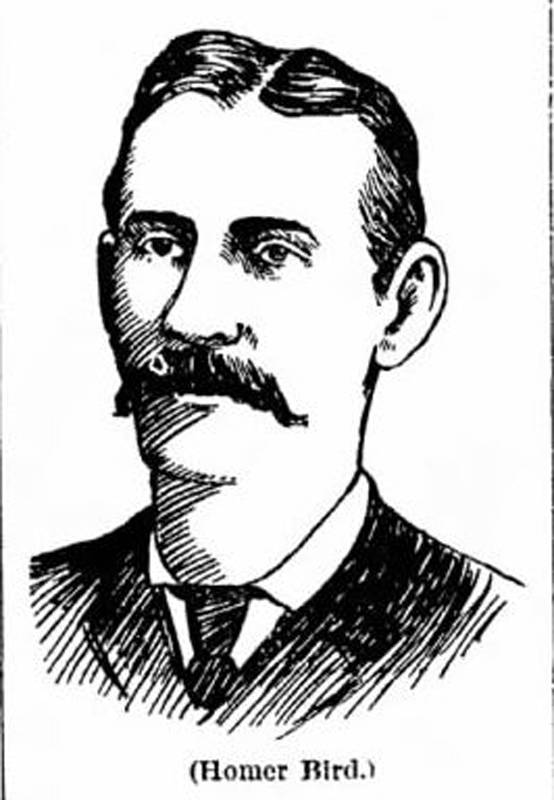

Spring typically signals the beginning of new life after a long a winter – however, in 1903 in Sitka, it signaled the end of one man’s life. March 6, Homer Bird was scheduled to be hanged at 12.30 p.m. on the gallows set up in the coal house on the wharf at the end of Lincoln Street. His was Sitka’s first and only court-sanctioned execution. The crime for which he was to pay with his life startled the country and attracted great attention.

Bird’s story begins in New Orleans, where he was born in 1858; it was there that he worked as a contractor and boss plasterer. He was married to A. Burke and was the father of five children. Not much is known about his life before leaving Louisiana for Alaska but it is certain that had it not been for the gold rush Homer Bird might have remained a prosperous businessman, his name unrecorded in Alaska history.

This disastrous trip to the Klondike started with Robert L. Patterson, a newspaper printer and publisher who got gold fever. Patterson advertised for partners to form an expedition to trek up the Yukon. Charles Sheffler, a young printer of German birth, answered this advertisement, but was unable to put up the money needed to secure his position on the crew. J.H. Hurlin, also German, worked as a bookkeeper for a boot and shoe company and was also a candidate. All Patterson needed now was a member with adequate capital to fund the trip, so he approached Homer Bird. Patterson and Bird quickly struck up a partnership. The four men and Norma Strong, a woman said to be Bird’s mistress, banded together. Norma Strong went by several aliases and was believed to be from Indiana; she found her way to New Orleans in 1892 and became Bird’s mistress two years later. In the press and at the trials, she was often portrayed as a woman of “tainted character” who cast sinful influence over Bird. Bird was portrayed as a respected citizen and beloved husband and father.

What was once intended to be an effort to take a share of the fortune of the Klondike gold fields quickly descended into chaos and crime. The party traveled west to San Francisco where they purchased a 30 by 7 foot house scow for living quarters, a gasoline launch and supplies for 18 months. The crew and their provisions embarked on the “Rufus E. Wood” and arrived in St. Michael on July 4, 1898.

By September, the team had traveled 600 miles up the Yukon River, to an area two miles from Camp Dewey, a logging camp. It soon became clear that they were not going to reach Dawson before winter set in and the party decided to build a cabin and stay until spring. The men quickly began to fight. Patterson wanted to build a 20 by 25 foot cabin and cut wood for the transportation companies. Bird objected on the ground that there was only one saw and one ax for the crew. Sheffler sided with Patterson and Hurlin, of whom Bird had been jealous. The three men insisted upon leaving Bird and Ms. Strong to set out on their own to prospect – Hurlin suggested taking the tools, launch and 3/5 of the remaining provisions. Tensions came to a climax on the morning of September 27, and from this point on accounts of the events vary. Sheffler and Strong testified in court that Bird sat on an embankment behind Patterson and Hurlin while they ate breakfast. When Strong asked Bird to come to the table he replied by shooting Hurlin dead in his chair. Bird then turned the gun on Patterson, shooting him in the neck and shoulder; Patterson fell into the Yukon River. Patterson bobbed up out of the water and Bird fired again, but missed. As Patterson crawled to shore, Bird threatened Sheffler but decided to spare him. Bird and Sheffler buried Hurlin. Strong cared for Patterson, but he died a few months later. About six months passed before men from the nearby Camp Dewey began to ask questions about the whereabouts of Hurlin and Patterson. Sheffler was able to escape Bird and make his way into the logging camp to tell the story of the crimes he had witnessed. “The Seattle Times” reported in 1900 that Sheffler and Strong tricked Homer Bird into going into Camp Dewey, where he was surrounded and forced to surrender. Soldiers then transported the alleged murderer to St. Michael in June 1899.

Homer Bird was confined to the Army guardhouse in St. Michael until the night of September 30, 1899, when he escaped. Captain Tucker stationed at the guardhouse reported that Bird somehow got hold of a saw and sawed his way through the floor of his cell. Thirty men were employed to apprehend Bird. He was captured three days later and was sent to Sitka on board the U.S. Revenue Cutter “Bear.” Bird appeared before U.S. District Judge Johnson in Juneau on Nov. 21, 1899. Despite being betrayed, Mrs. Bird made the long journey to Juneau with her youngest child to witness the trial. Court convened after six days with the jury returning a verdict of guilty of first degree murder. Bird was sentenced to death by hanging on Feb. 9, 1900.

John Malone, Bird’s defense attorney, secured a stay of execution from Governor Brady while an appeal was made to the Supreme Court. The court heard the arguments on Jan. 21, 1900 and rendered a decision one month later – Homer Bird would be granted a new trial. District Judge Melville Brown held Bird’s trial in Skagway. A guilty verdict was returned on Christmas morning 1901. In an effort to save his life, Homer Bird made another appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court with a decision announced on Nov. 17, 1902, and charged his wife with making appeals to President Roosevelt. Despite Mr. and Mrs. Bird’s pleas the Supreme Court upheld their decision, setting an execution date of March 6, 1903. Bird was returned to Sitka to await his fate, and was kept in the jail set up in the Old Russian Barracks on Lincoln Street. U.S. Marshal James Shoup purchased second-hand gallows from King County, Washington, and set it up in the coal house on the government wharf.

On the evening of March 5, Homer stayed up all night writing a statement to make the next day. After getting three hours of sleep, Bird was awakened by Rev. William S. Bannerman of the Presbyterian Church. According to “The Alaskan,” Sitka’s newspaper, Bird was given a hearty breakfast at 10 a.m. of eggs, steak, rolls and coffee. After the mail steamer “Bonita” arrived at 1 p.m. without word from President Roosevelt, Bird drank one last cup of coffee, walked the 10 yards from the jail and ascended the stairs of the gallows. Before a jury of witnesses, he read a long statement, asserting, “I was convicted on the testimony of a vile woman and bad man (The Times–Democrat, March 28, 1903).” “The Alaskan” stated that after being secured the trap was sprung, and Bird was pronounced dead at 1:41 p.m. A New Orleans based newspaper, “The Times-Picayune,” reported that prior to the date of execution Mrs. Bird and her children kept vigil for two days waiting for word from the President that Homer would be spared, but clemency never came.

Bird’s funeral service was held at the log Catholic Church. Prisoners carried the coffin to an area near the military cemetery and buried it in a marked grave, where Homer Bird laid undisturbed for more than 50 years. According to “From Sitka’s Past” by Robert DeArmond, a survey conducted for a new connection to Sawmill Creek Road unearthed Bird’s grave, and his remains were later reburied in an unmarked grave.