Harvey Kitka/Yansh ka owoo of the Sitka Kaagwaantaan [Wolf] Clan was a fisherman, as was his father, grandfather, and the many generations of his ancestors that came before. At the age of twelve, Harvey started seine fishing with his father, Herman, a man whose legendary skills as a fisherman lives on in Sitka lore. “Fishing was a way of life for our people,” explained Harvey. “Everything we got was from the ocean and the land.”

For thousands of years before the arrival of Russians or Americans, the salmon harvest played a fundamental role in the lives of Southeast Alaska Natives. More than mere subsistence, salmon helped to define Tlingit economy, resource rights, and culture. Salmon streams were owned, guarded, and passed down from generation to generation.

The 1867 Alaska Treaty of Cession, in which Russia ceded its claims on Alaska to the United States, significantly altered Tlingit salmon economy. As Americans began arriving to capitalize on Alaska’s fisheries, the growth of commercial fishing and the seafood canning industry threatened to exploit the salmon harvest. The terms of the Treaty of Cession did not recognize Tlingit landownership, including claims on salmon streams, but that did not stop the Tlingit from asserting their traditional fishing rights.

From the opening of the first cannery in Sitka, the Tlingit set a precedent for future commercial fishing and cannery operations. In 1878, the Cutting Packing Company built a cannery at Starrigavan Bay, just north of downtown Sitka. It was the second operational cannery in Alaska, just behind the North Pacific Packing Company at Klawock. The Cutting Packing Company sent supplies and a Chinese work crew to Sitka, but as the boat approached the shore, the crew was met by a group of Tlingit men who insisted that the Chinese not be allowed to land. After much negotiation, the men agreed to let the Chinese work for the season making tin cans, provided the cannery purchase their salmon supply from Native fishermen.

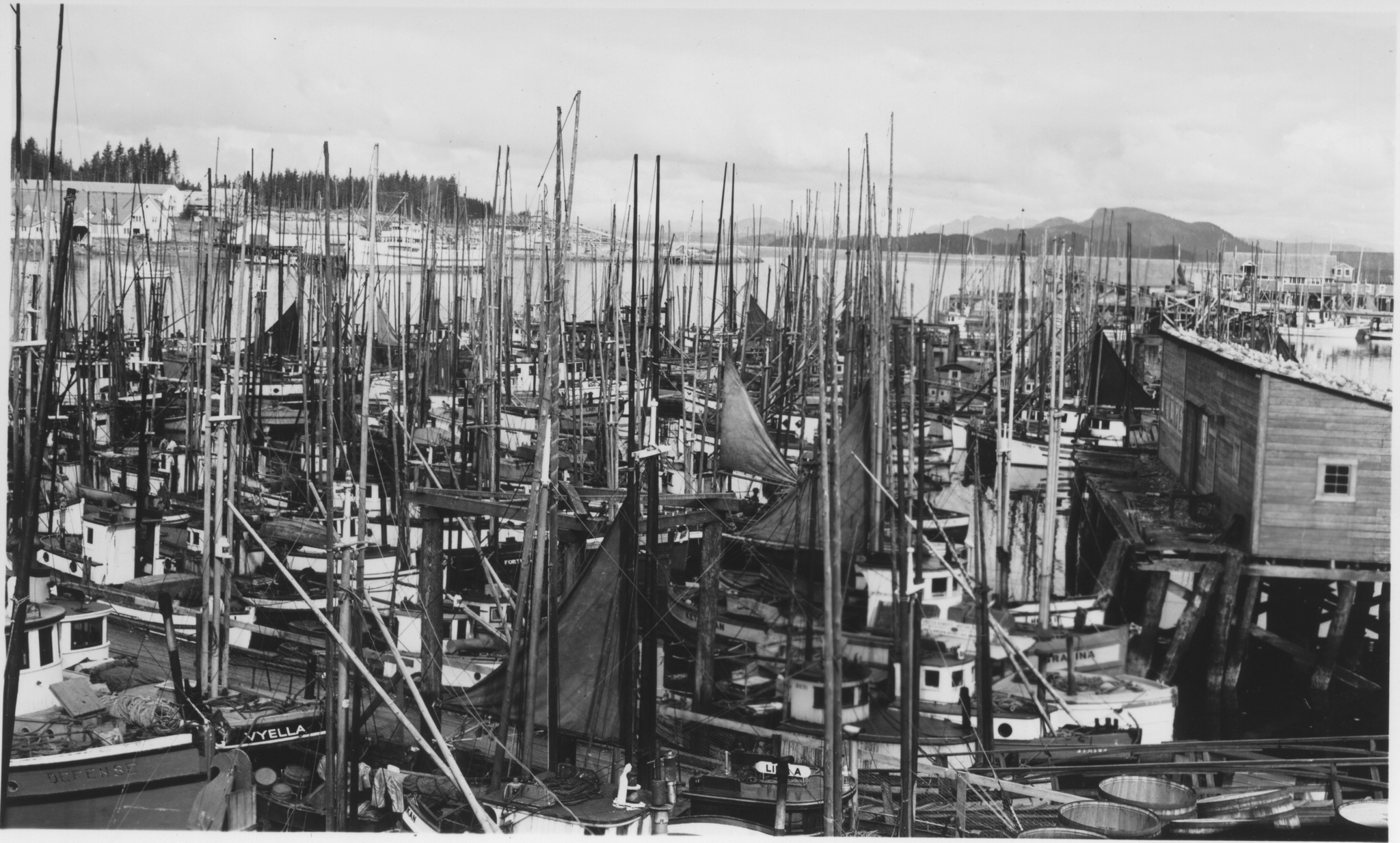

As canneries and cold storage facilities popped up all over Southeast Alaska, the businesses looked to Alaska Natives, who held a near monopoly on the seine fishing fleet, to supply them. Harvey Kitka explains that the knowledge passed through the generations, born from a deep connection to the natural environment, meant that Alaska Natives knew when to fish, where to fish, and how to fish. “The most skilled of the Native seine fishermen could catch over 100,000 fish a year,” he said.

In 1885, the first fish trap appeared in Alaska. The traps operated with brutal efficiency and canneries had less need to depend on seine fisherman for salmon. A surplus market drove the price of salmon down to just pennies per fish, leaving the primarily Native seine fishing fleet with little profit for their efforts. Fish populations plummeted and by 1953 President Eisenhower declared the Alaska salmon fishery a federal disaster.

Fishermen banded together, refusing to vote for impending statehood unless the State constitution included a ban on fish traps. “Most of the fishermen signed petitions. We’d have never gotten statehood if the Native community and the fishermen did not get behind it,” says Harvey. Their efforts paid off, the vote ending with overwhelmingly favorable results for Alaska’s fishermen. Alaska joined the Union in 1959 and the use of fish traps came to an end, but the damage was done. Streams that once danced with salmon lay still.

Searching for a way to rebound salmon populations and revive Alaskan commercial fishing, the state legislature created the Limited Entry Act in 1973. By regulating the number of commercial boats in a particular fishery, the program strove to promote conservation and the economic health of the industry. At first, local people could get a fishing permit for no cost if they economically depended on fishing and had fished commercially for a number of years. The law allowed fishermen to freely transfer their permit by gift, sale, or inheritance –by doing this, the law aimed to keep the profits from one of Alaska’s most valuable natural resources local. It did not work.

For those fishermen who had to purchase permits, pay a crew and maintain both boat and gear, the pressure to make a profit intensified. Their strategies often favored expensive fishing technology. The struggle to afford new equipment and compete with other fishermen, coupled with the rising monetary value of permits encouraged many Alaska Natives to sell their limited entry permits–often to non-local, wealthy fishermen. Although the sale could bring a substantial reward, those living in fishing communities without a permit soon found their work prospects limited. Harvey Kitka remembers, “By the time the 1990s rolled around, you could count on one hand how many Native-owned seine boats were left. In Sitka, there were only two. Many of the boats…they just became skeletons on the beach.”

In the span of a little more than one hundred years, commercial fishing went from being a way of life for Southeast Alaska’s Native community to a bygone era. When asked if he regrets giving up his career as a seine fisherman, Harvey Kitka said, “Sometimes. I was groomed to run a boat, all my brothers were.”

Portions of this article first aired on KCAW FM in August of 2016 on Sitka History Minute, a weekly radio program written by the Sitka History Museum. Research for this episode was funded in-part by the Alaska Historical Society’s Historic Canneries Initiative.