My last column focused on the Dyea-Klondike Transportation Company (or DKT Company), the first and shortest of the three aerial tramway lines operating on the Chilkoot Trail. This column will center on the second of the Chilkoot’s three aerial tramway lines – the second one to become operational and the second longest.

The Alaska Railroad & Transportation Company (or AR&T Company), also known as the Alaska-Pacific Railway Company or the Oregon Improvement Company, was one arm of the vast Pacific Coast Steamship Company, a corporation which operated both railroads and steamship lines along the West Coast at the time of the Klondike gold rush. Completed just after the DKT Company’s line, the AR&T operation boasted a longer length, more freight-carrying capacity, and higher technological sophistication than the DKT tramway. The AR&T Company, in turn, was outclassed by the Chilkoot Railroad & Transport Company (CR&T), the last, largest and longest of the three aerial tramways to operate on the Chilkoot Trail and the subject of my next column.

The AR&T Company showed interest in the area near the beginning of the gold rush. In early December 1897, the company established a claim for a trading and manufacturing site at Pyramid Harbor, 20 miles or so to the south of Dyea. In late December that year, company representative A. R. Cook located a 36 acre wharf site on the east side of Taiya Inlet, approximately two miles southeast of Dyea. Soon afterwards, he also located a 10-acre site a mile north of Dyea for a “station and warehouse.” By mid-January 1898, Cook had also filed for a 10-acre depot and warehouse site, “twelve miles from Dyea, near Sheep Camp.”

Unlike its competitors, the AR&T Company did not advertise in the local newspapers and news about the construction of its aerial tramway did not identify the company by name. In addition, two other tramways were being built at around the same time making it difficult to separate the precise history of each company. Given that the word “railroad” was in the company’s name, company officials probably intended that a railroad of some type would be built from Dyea as far north as the tramway site, but as far as known, no railroad was ever begun. It can only be assumed that sometime after mid-January 1898, the company abandoned its railroad plans.

It is not known when construction of the AR&T Company’s aerial tramway began, but original estimates called for its completion by March 1, 1898. The first physical evidence of the line’s existence dates from April 3, 1898. On that date, the huge Palm Sunday avalanche cascaded down upon the Chilkoot Trail, killing more than 70 stampeders. The slide tumbled dangerously close to the AR&T powerhouse, which was located approximately two and a half miles north of Sheep Camp. As the powerhouse was the nearest building to the slide site, some victims of the avalanche were brought there. Robert F. Graham, a stampeder, noted that 23 bodies, all of which were construction workers for the CR&T Company were brought to the powerhouse by April 7. At the time of the snow slide, the much-ballyhooed (and much-delayed) CR&T tramway was better known to the stampeders than the AR&T tram, therefore, many assumed that this powerhouse belonged to the CR&T Company. The AR&T Company was not known to be operating at the time of the avalanche.

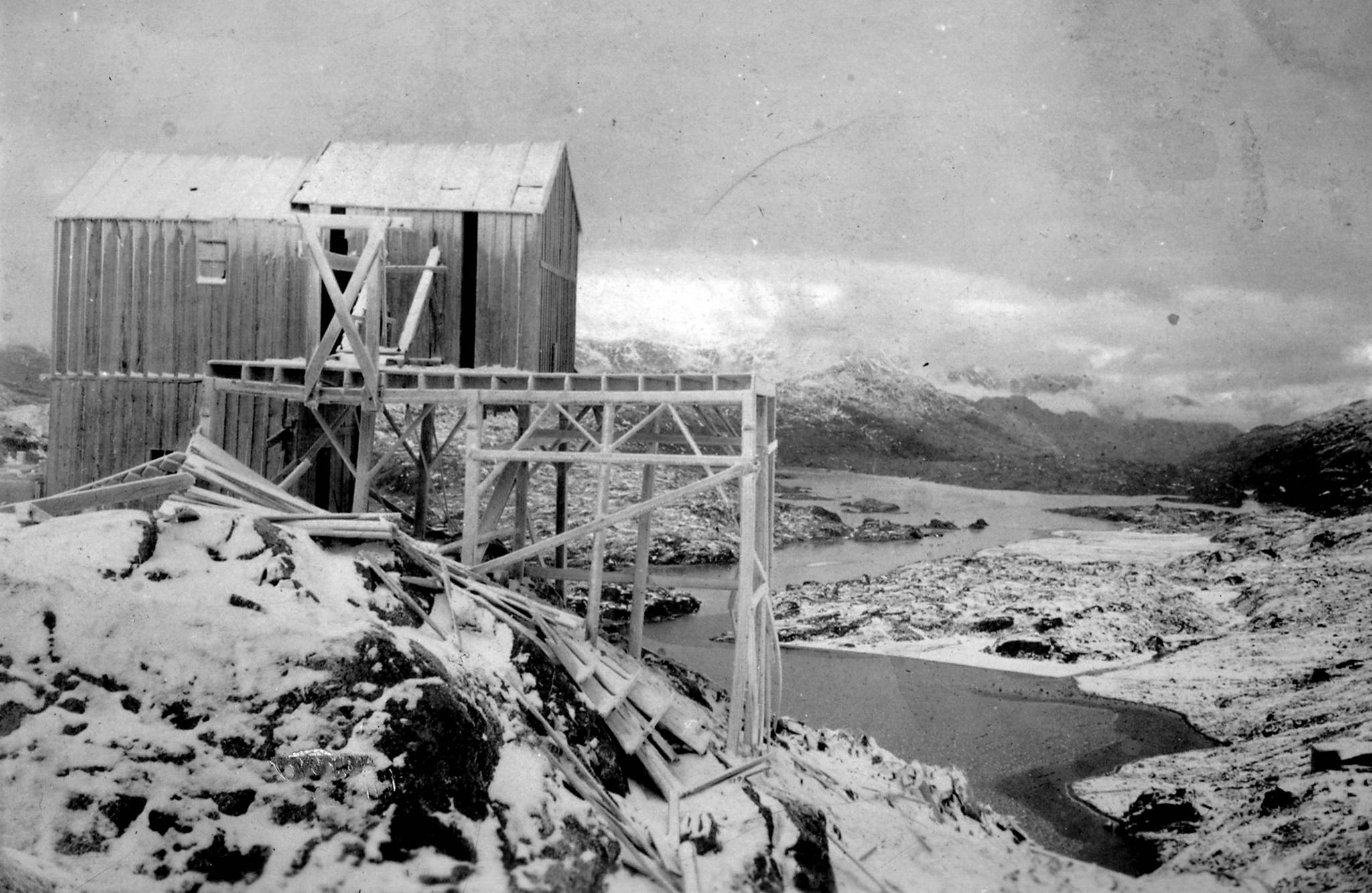

The powerhouse built by the AR&T Company was sturdy and part of it was constructed on pilings. It is not known why the firm chose to locate its powerhouse where it did. As a gasoline-powered tramway it did not need to depend on either water or wood; it only needed a relatively level area for its powerhouse. The building could therefore have been located most anywhere along the trail, but its location, off the main trail and midway up Long Hill, appears perplexing. Perhaps the planners of the proposed railroad felt that the tracks could go no higher than this spot. The AR&T Company, unlike the other aerial tramways, did not operate pack trains or wagons in conjunction with its operations. Neither did the firm openly contract services to independent freighting companies.

The AR&T tramway opened sometime after mid-April 1898. Powered by a gasoline engine, the line carried its cargo about a mile and a half northward with a vertical rise, over very rugged alpine terrain, of about 1,345 feet to the Chilkoot Summit. The Company’s southern terminal stood at an elevation of 2,133 feet and the northern terminal at 3,478 feet. Carriages were limited to a capacity of less than 200 lbs. each. Goods were carried, very slowly, over the pass. Going up Long Hill, the tram cables drooped so low between the towers that many packers could help themselves to the cargo. The AR&T line terminated at the station immediately north of the Chilkoot Pass just inside Canada and slightly west of the trail.

The AR&T line was a “Huson Patent Automatic Wire Rope Tramway” manufactured by C. W. Badgley & Companyof San Francisco, California. Patented in 1882 by Charles M. Huson of St. Louis, Missouri, the Huson design dominated the aerial tramway market in the American West by the early 1890s. Several dozen were in use, mainly at mines all over the Rockies by the time the Klondike gold rush began. The AR&T line was one of the last Huson tramways ever built. As such, it represents the greatest degree of sophistication and practicality achieved by single-rope tramway systems. Single-rope tramways employed a single, continuous, moving loop of wire rope to which the load-bearing carriages were attached. The wire rope, with the carriages clamped to it, moved through sheaves attached at the top of the line’s towers (called derricks or stations by the manufacturer), delivering the carriages to and from the two terminals located at each end of the line.

This is as opposed to the double-rope or Bleichert system, where carriages, pulled by a moving traction rope, moved along a stationary carrying rope. The CR&T double-rope tramway was a Bleichert system manufactured by the Trenton Iron Works of Trenton, New Jersey. This company dominated the double-rope tramway industry in America just as Badgley dominated the single-rope market.

The small capacity of single-rope tramways was compensated for by the simplicity of their design, the fact that they could be quickly and inexpensively built of lightweight, easily transported materials, and required no advanced engineering skills to maintain. The AR&T Huson tramway, however, was erected on the Chilkoot just at the time when demand for the larger capacity, double-rope tramways, which required much more extensive resources to build and maintain, was beginning to eclipse the need for the more frontier-style single-rope systems.

The side-by-side operation of the AR&T single-rope and CR&T double-rope tramways along the Chilkoot Trail may have been the only instance where the two designs competed directly against each other. In this competition, the CR&T tramway proved more successful, providing an economical and efficient way to lift materials over the pass. The success of the Bleichert double-rope design on the Chilkoot Pass symbolically demonstrated its superiority over other systems. While tramways of the Bleichert design continued to be expanded and improved after the gold rush, the single-rope tramways fell into oblivion.

The AR&T Company did not operate long. In May 1898, the huge CR&T tramway was finally placed in operation. The three tramways competed against one another for only a few weeks and then in June 1898, they signed a working agreement to charge a uniform rate (7 1/2 cents per pound) to haul goods between tidewater and the lakes. This combined operation was called the “Chilkoot Pass Route.” The AR&T tram may have operated as late as the latter part of June 1899, when the entire operation was purchased by the White Pass & Yukon Route railroad (WP&YR), but no known accounts tell of the tram company’s operation after the summer of 1898. By that time its usefulness was clearly over, the stampeders had gone “inside,” and those wishing to haul freight northward either sent it on the more sophisticated and much longer CR&T tramway or used the WP&YR railroad out of Skagway.

The AR&T equipment was removed in February and early March of 1900. Workers took almost everything of value. In 2001 park service archaeologists thoroughly documented the remains of the AR&T powerhouse, a nearby outbuilding, and a few associated artifacts. They have also documented the other remains of the AR&T system, consisting of 10 tramway towers on the US side of the trail, with the last AR&T tower and terminal located just north of the Summit in Canada.

The AR&T powerhouse at Long Hill was a two story, gable roofed, timber framed building about 45 feet by 105 feet in size. In addition to housing the gasoline engine, southern terminal sheave and the drive mechanism of the aerial tramway, the building must have functioned as a warehouse and possibly as a bunkhouse for workers. It was the largest building anywhere along the U.S. side of the Chilkoot Trail north of Dyea and is now the single most massive archaeological ruin of the Chilkoot Trail. The collapsed powerhouse building is now reduced to an expanse of deteriorating lumber some 1,673 square feet in area, falling down a slope overlooking the west side of the Taiya River in the upper Long Hill area.

Present in relative abundance at the site, is a number of square-breasted, five gallon-capacity fuel cans. Since the AR&T system was driven by a gasoline engine, the fuel for that engine must have been brought up in these small cans. Other artifacts found at the site include pieces of Granite Ironware kitchenware, iron machinery fragments, a fragment of a Yukon-type lightweight portable stove and a few tin cans fragments which probably contained foodstuffs.

Another interesting artifact, although not found at the powerhouse site, is an original paper invoice from the AR&T Company that survives in the park archive. It is printed with the name of the company and Stonehouse as the company’s place of business. Stonehouse proper – if there can be said to be such a thing – is considered by today’s regular users of the Chilkoot Trail to mean a large boulder in a small triangular patch of land contained by the confluence of the Taiya River and an unnamed tributary to its west, about a half mile south of the powerhouse site. Teite – a Tlingit word meaning “stone houses” or “rock shelters” – are also found south of the powerhouse site.

• This article was researched and written by Frank Norris, former seasonal Historian at Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park in Skagway and added to and edited by myself, Karl Gurcke. It was part of a larger Historical Structure Report on the Chilkoot Trail, completed in 1986 but never published. Portions of that report, complete with references can be furnished by request at no cost if you email me at karl_gurcke@nps.gov. For the current condition of artifacts on the Chilkoot Trail, I have relied on Eve Griffin and Andy Higgs, both former seasonal Archeologists for the National Park Service and my own observations. An earlier version of this article was read over the air on KHNS, the Haines public radio station.