The first time Brendan Jones moved to Sitka, he was 19 years old and lost.

He volunteered at Sheldon Jackson Hatchery in exchange for room and board. He built a hut and lived in the woods off Indian River. He wrote for the Daily Sitka Sentinel. Most of all, during those nine months he fell in love with Alaska.

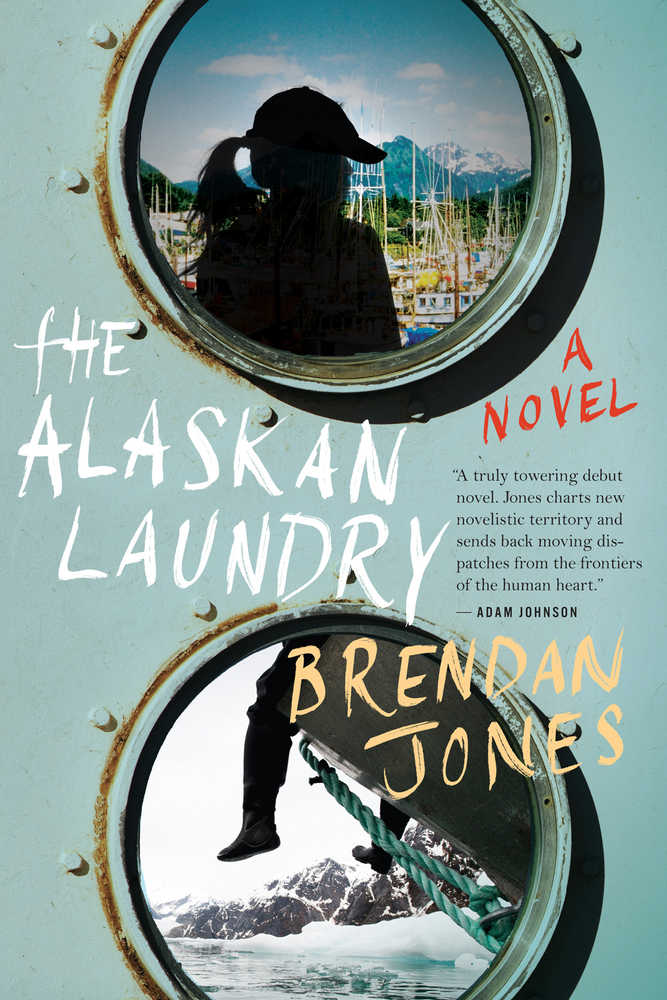

That experience was a formative one both for him and his debut novel, out this spring. “The Alaskan Laundry” follows East Coast expat and boxer Tara Marconi as she moves to Port Anna, Alaska in an attempt to recover from her mother’s recent death, to figure out what she wants, and purge herself of anger through work, self-exploration, and friendship. Over the course of the book, she climbs the fisheries ladder from hatchery assistant to crabber on the Bering Sea, pursues her dream of owning the tugboat docked at the Port Anna harbor, and comes to know life in Alaska. In the sixth chapter, Jones writes:

“When she thought about the East Coast, she saw it as cities revolving around the sun of New York — Philadelphia like Mercury, Washington like Mars, Boston, Saturn. Here on this island, it was as if her planet had slipped its ellipse and she was floating around some gentler, more mysterious sun. She couldn’t see it yet, but she could already feel it, the few times when she stopped fighting and allowed herself to be guided by this new force. It was somewhere in those woods, hidden beneath the ice fields, deep in the river valleys.”

Jones, who worked on the novel for 10 years, was sitting at Highliner Coffee in Sitka when he began to write Tara’s character.

“(Highliner Coffee) is run by a woman from Petersburg with real fishing history,” he said. “She’s got this wall of framed photos, and they’re all women commercial fishing.”

One in particular struck him and became the genesis of Tara, but the older female fishermen he’s met in Sitka “are just really amazing women — incredible to talk with, because they make a point that they were never made to feel like outcasts in the fishing industry,” he said. “It’s so much about whether you were catching or not, not anything to do with gender.”

Initially, Tara wasn’t the main character — she was one of many. She ended up, however, being “the last character standing.” Just the same, in addition to Tara, “The Alaskan Laundry” is filled with colorful Alaskans whose characters ring true. Newt, one of Tara’s closest friends, tells her:

“‘Important thing is, I’m stayin’ clean as a broke-d*** dog up here with my eye on that big steak in the sky. Because lemme be the one to tell you — all of us in this state are just getting whipped around on one continuous cycle, washed clean of our sins. You wait it out, be patient, work hard, keep your eye on that channel marker, and by my word there’s a payoff.’ His skin appeared transparent in the last rays of the sun. A purple vein zigzagged down his forehead.” The idea of the laundry cycle, Jones has said, stems from a conversation he had with “a pickled fisherman” years ago.

Jones’ life hasn’t followed the same trajectory as many modern-day writers.

Instead of getting an MFA (Master of Fine Arts,) he did a carpentry apprenticeship program for Alaska’s Local 1281. In Philadelphia, he started a business that had 24 employees and did $1.5 million in business in one year. In the summers, he’s commercial fished for years.

In 2011, after living in Philadelphia for five years, he “stupidly” leaped off a waterfall — and slipped. Though he ended up being okay, it scared him.

“It turned my head around. I decided where I want to be is Alaska,” he said.

After he sold his house and his share in the construction business, he ran into the same problem many Alaskan would-be home-buyers do: prices.

Then he saw a World War II-era tugboat for sale in Sitka. The Adak is a sister tugboat to the Challenger, which sank in Gastineau Channel last year. With a little TLC, it’s been a great home for him, his wife, Rachel Jones, and his daughter Haley Marie, he said.

Much of “The Alaskan Laundry” was written with the help of a Stegner Fellowship. The Stegner, one of the most coveted fellowships a writer can get, gave Jones two funded years at Stanford to focus on his writing.

“I couldn’t have financially done so much of the work on this timeline without that Stegner,” he said. “It was such a blessing.” Stanford also gave him a community of fellow writers, and the opportunity to work with acclaimed authors like Tobias Wolff and Adam Johnson.

“The Alaskan Laundry” has been through a lot of changes in the more than 10 years it’s been in the works. In 2013, Jones published an excerpt from the book in the literary journal Ploughshares. That excerpt is “wildly different from the book as it is now,” he said. “I ended up rebuilding the boat as it was going down the river, in a sense — going plank by plank instead of sinking the whole thing and starting over.”

Initially, Tara moved to Sitka itself. Then Jones started thinking about the ethics of naming, say, a traditional spots for gathering mussels. He also started thinking about the book “The Yiddish Policemen’s Union,” by Michael Chabon. “He made up everything except the name ‘Sitka,’ and I think he did a real disservice to the people living in the town,” Jones said.

Once he came up with the name “Port Anna,” taking a cue from David Guterson’s “Snow Falling on Cedars,” which imagines a new name for Bainbridge Island, the book “started to breathe more,” he said.

He’s on his book tour right now, and will be doing readings in Sitka, Juneau, Homer and Anchorage. He also wants to schedule one in Haines and Fairbanks, he said.

His Sitka reading is May 17, 6 p.m. at Old Harbor Books; his Juneau reading is scheduled for June 4, 6 p.m. at the Mendenhall Valley Public Library.

“I definitely wrote it with Alaskans in mind,” Jones said. “What’s most important to me is that it hits home with people that live in the state, because that’s where I make my home. It’s a book written in honor of the state I fell in love with at a very young age. I see it… as a way of giving back to Alaska. I was such a lost cookie, and the community of Sitka and Southeast gave me so much… that I needed where I was at the age of 19.”

• Contact Capital City Weekly managing editor Mary Catharine Martin at maryc.martin@capweek.com.