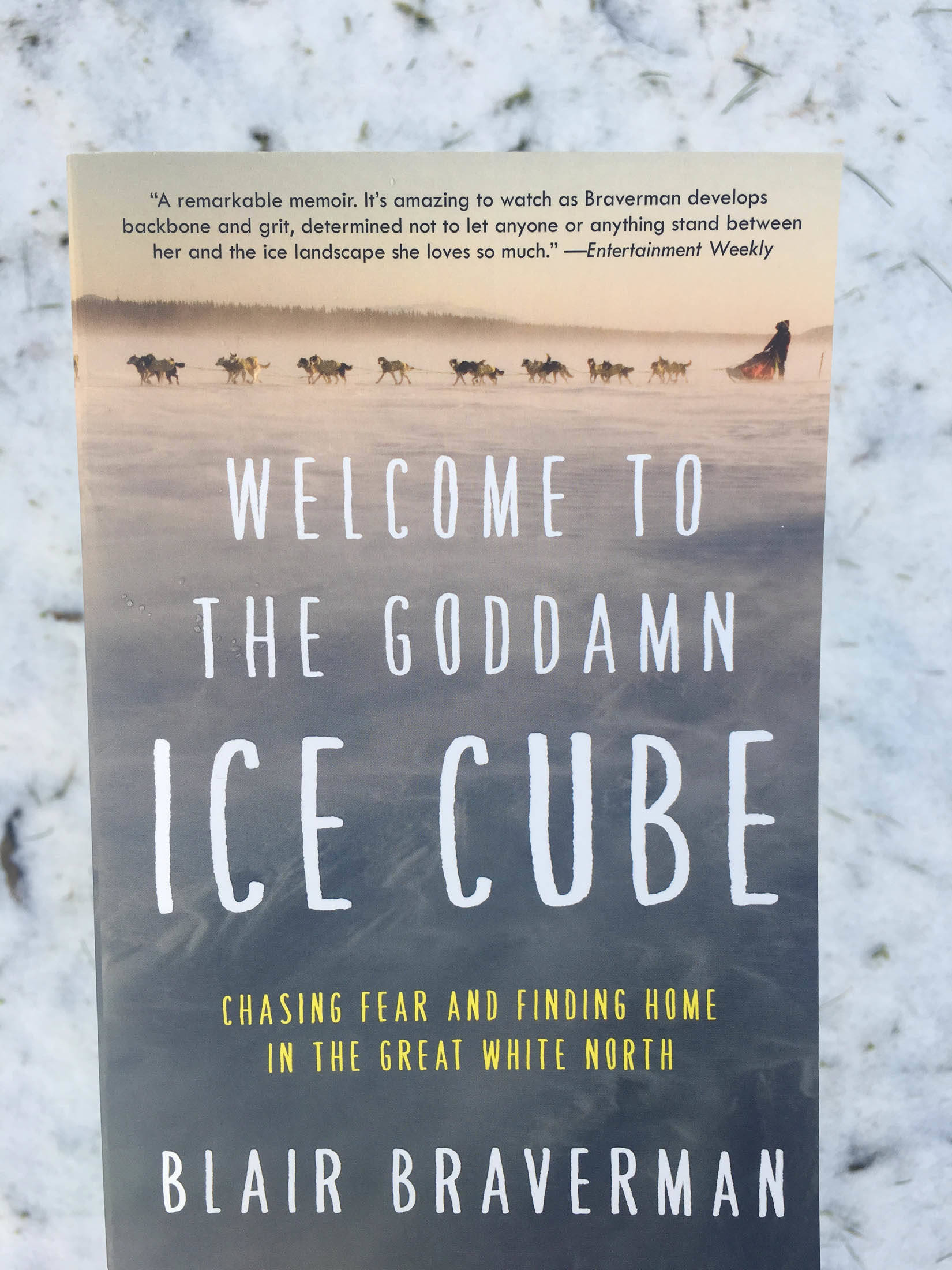

It can be intimidating to give books to a bookseller. But that is just what happened one summer when a young man with a shy smile gave me Blair Braverman’s “Welcome to the Goddamn Ice Cube.” I was in the middle of preparing for my first week-long group wilderness adventure, and my imagination was working overtime with what-ifs. I turned to the gift looking for a distraction. What I found was a story of thrilling adventure, hidden peril, and a woman’s brave search for her place in the north.

Ice Cube is a book about the idea of, and one person’s experience with, Alaska. It’s also about Braverman’s experience of Norway and her path to dogsledding, a skill she learned at a folk school described as a “cross between hippie commune and survivalist camp.” Much of the book is about her deep friendship with an old man named Arild who owns a grocery store. It’s interspersed with the thrill of wilderness adventures and finding yourself in the middle of them. Through it all, Braverman works through her experiences with different forms of sexual violence, and gives voice to what it looked like for her as trauma lingered, an uninvited guest, long after events themselves took place.

I enjoyed the way Alaska existed as a concept in Braverman’s book long before she set foot in the state. She grew up in California but as a child was obsessed with everything about the north, first with the Iditarod, then the authors Farley Mowat and Gary Paulsen as she grew. It was this fascination that drew her to a high school exchange program in Norway, and that brought her to the home of her first abuser.

“I doubted myself so violently that I split into two: the part that was afraid and the part that blamed myself for my fear,” she writes. Braverman pulls out pieces of herself for the reader as she walks through her own responses and reactions. No two people respond to trauma in the exact same way, but Braverman’s not trying to tell another person’s story. She’s telling hers.

Braverman returned to Norway, this time to attend a folk school to be trained in the intricacies of working a dog kennel. Throwing herself into the mercies of the bitter Arctic weather, she writes, “It was refreshing to be afraid of something concrete. I was no longer scared of some unknown force, of confusion; no, I was afraid of hypothermia. I was afraid of being stranded in the wilderness. I was afraid of crashing the sled. I was as afraid as I’d been in [her Norwegian host-father]’s house, maybe even more, but suddenly that fear didn’t make me crazy: it made me brave.”

Working with dog teams eventually brought her to Alaska, working on the Juneau Icefield. I saw echoes of myself in the way she threw herself into the male-dominated, isolated world because the adventure was worth whatever other risk the experience may have held. The dangers she found there were many, including the living conditions of the camp itself. But they also came in the form of her first adult relationship — with someone who did not understand the idea of consent. Someone who eventually became inextricably linked with her experience at the job of a lifetime on top of a glacier.

“Of course, I knew that [her ex-boyfriend] was not Alaska. But he was part of it, represented some hard masculinity that seemed to thrive in the north, and that I didn’t want to be shoved up against. Not again. I wasn’t sure if I could handle it.

But at the same time, I wasn’t sure I’d feel safe – anywhere, really – until I had proved to myself that I could.”

And so Braverman found her way to Norway again, and it’s here the book comes alive with quirks of remote Scandinavian life. Hints of threats continue to echo, but as Braverman comes to terms with her past the reader is along for the ride.

This is not a soft book, though there are vivid depictions of tenderness and friendship, along with adventure and humor. (Let’s just say the headmaster of the folk school makes a memorable entrance.) For too many, it will likely bring up memories of their own experiences with violence. But Braverman’s ability to find words for her trauma, and her process of healing, were a deeply powerful tonic I feel thankful for receiving.

Eventually she creates her own north on a farm in northern Wisconsin, with room for beauty and peace amidst the danger and harsh edges, with her partner and a sled team. And, according to her website and recent publicity, Braverman is not through with Alaska. She is currently training to qualify for the 2019 Iditarod.

I think my favorite part of being a person who trades in words is being surprised when the right book crosses my path at a perfect moment. If any of these themes are resonating with you, maybe now is the time.

• Chelsea Tremblay lives and writes in Petersburg.