All we had for transportation, when we first lived way out in the bush when I was a kid, was a thirteen-foot Boston Whaler powered by a 50hp Mercury outboard engine. Although my dad risked his life crossing Clarence Strait on a weekly basis in the small skiff to commute between his logging job in Thorne Bay and where we lived, my mom and us kids almost never went anywhere.

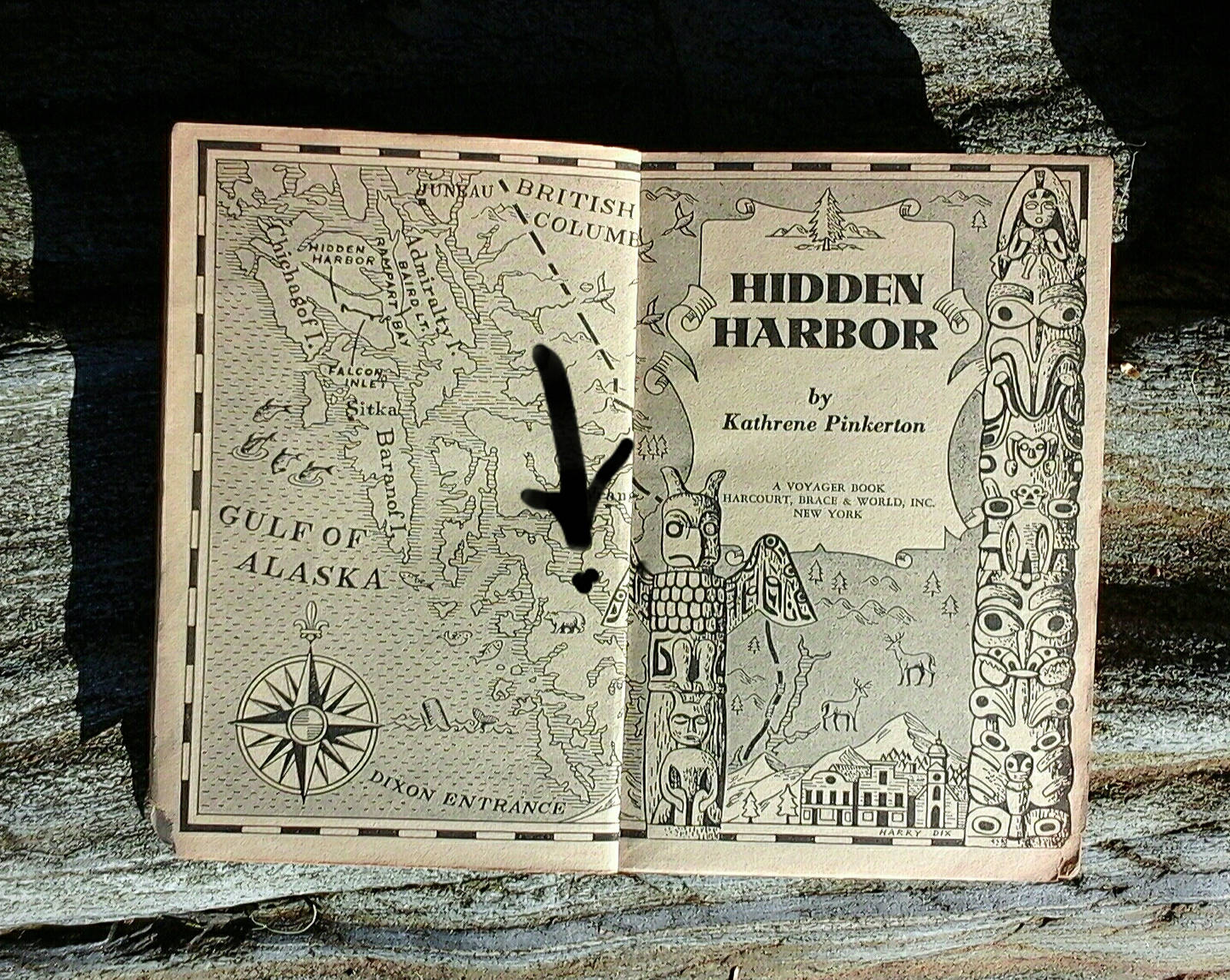

As an adult, I’ve rarely met anyone who understood what that kind of isolation was like. Then I read “Hidden Harbor” by Kathrene Pinkerton.

The opening scene is of a young man, Spencer Baird, waiting for the tide to go out so he can check the hull of their family sloop for dry rot. To his shock and horror, he finds the keel riddled with it. “He just lay there…he could replace the riddled strakes but a new keel was impossible. Might as well cut a man’s rib from his backbone and expect to give him a new spine.”

He worries about the remote place where he and his family live by themselves: “It was sea country, its only roads the waterways of the sea’s invasion…. Everywhere, the Pacific crowded into the heart of the mountains. It had flooded the outer range, turning ancient valleys into winding channels and wide straits, mountain peaks into islands, mountain shoulders into bold capes, and old river beds into long inlets and deep bays…. A man without a stout boat was imprisoned.”

My dad must have felt exactly this until a man in Ketchikan who’d asked him to rebuild his 32-foot boat gifted it to him when he had to leave Alaska. My dad built ways and a grid for it and a fisherman friend towed it to where we lived. And then my dad went to work. For years we played near it and watched as entirely by himself, using his mobile sawmill for lumber, he replaced ribs, the bow stem, 30 planks, decks, the stern, pilot house, built a hold, put an engine in it, and finally had himself a sturdy, seaworthy boat that was destined to weather all kinds of storms as it was put to work wood logging, fishing, grocery and fuel hauling, and taking us kids to school in Meyers Chuck when the weather was too marginal for the skiff. We were no longer imprisoned by Southeast Alaska’s “sea country.”

Kathrene Pinkerton wrote Hidden Harbor in 1951, but it’s set in 1910. (A time when Spencer could say to his younger brother, who suggests moving to a town to get a job, “Douglas! That’s no place for a kid. Toughest mining town in the country, and Juneau’s not much better.”) It was also a time of fish traps—and piracy of those traps, which plays a large part in the novel’s plot.

I was astonished, as I continued to read, just how much the lifestyle in Southeast Alaska during the pre-World War I years was like my childhood in the 1980s. Pinkerton perfectly captures what it’s like to rely solely on family for everything, to live off the land, and how to use the natural aids of tide and an abundance of trees to accomplish seemingly impossible feats.

For example, a wealthy boater takes his expensive, brand new cruiser called the Taku into uncharted waters and runs it aground on a reef. The Taku sinks, practically in Spencer’s front yard. It’s given up as a lost cause by the surly owner who sells it to Spencer, who’s desperate for a new boat, for a hundred dollars.

The problem is: how can Spencer raise a heavy, forty foot boat resting on the edge of a drop off in thirty feet of water with only his family (father, mother, brother, and sister) for labor, and a dinghy and rowing skiff for towing power?

His answer to the seemingly insurmountable problem is exactly the sort of thing my dad would have done in the same situation. Using the tide, the lifting power of two large, sixty foot-long cedar logs, and a couple hundred feet of cable with attached cable clamps, he manages to float the Taku off the reef and haul her out on dry land to repair her. Every aspect of the recovery is taut with authentic detail and suspense, with all the worry of the things that could go wrong.

The rest of the book is about how Spencer’s life expands as master of the Taku and we see a Southeast Alaskan legend in the making as he takes on a larger role in the bush community, including fighting to have the territorial government do something about the many sinkings and wrecks caused by the lack of proper, accurate charts and markers. There are family issues, piracy, gunshot wounds, visits to Juneau, and even a hint of romance. The characters are vividly drawn, the dialogue is sharp and at times dryly humorous, and the various conflicts have interesting nuances based less on black and white ideas of morality, and more on personality differences and different ways of viewing the world.

Kathrene Pinkerton’s books are sometimes hard to find and expensive, but when it comes to capturing the rural Southeast Alaskan’s sturdy sense of independence and can-do initiative, as a fiction writer I have found no equal to her.

• Tara Neilson writes the bimonthly Capital City Weekly column “Alaska for Real.” She lives in a floathouse between Wrangell and Ketchikan and blogs at www.alaskaforreal.com.