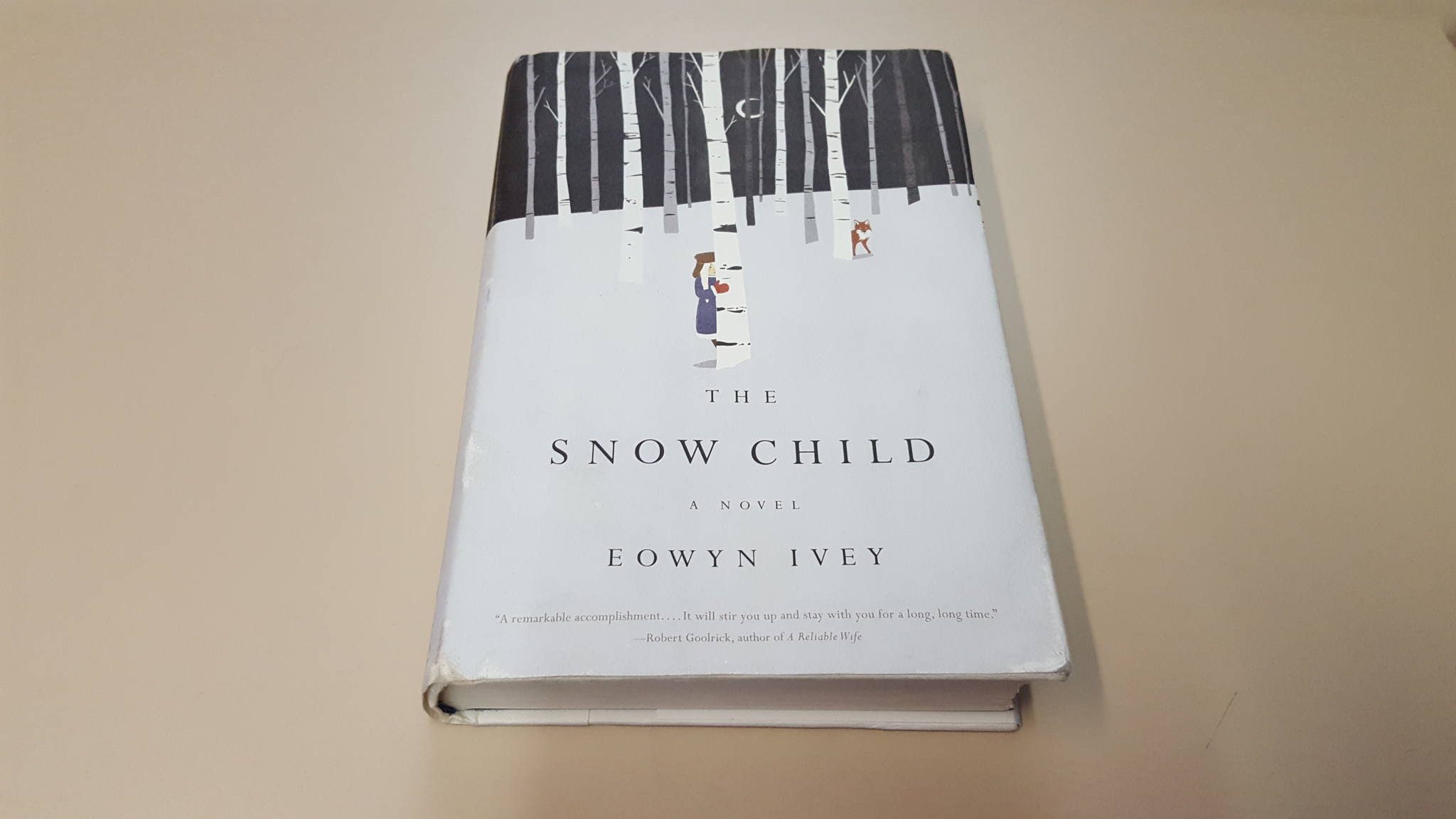

Finalist for the 2013 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction “The Snow Child,” the debut novel of Alaskan writer Eowyn Ivey, is a book I’ve been meaning to read for years. Now that it’s being adapted for the stage and set to be performed at Perseverance Theatre this June, I knew it was time to pull out the copy buried in my ever increasing To Be Read pile.

It felt fitting to open this book on a short winter day, twilight long since come and a streetlamp casting an orange glow on the freshly fallen snow outside my window, reminding me: spring is a long ways yet. Now that I’ve made it to the final page and overlook the Gastineau Channel glimmering from early afternoon sun, I am also reminded: spring may be a ways yet, but it will come.

How to describe this book? It’s many things all at once: a love story with echoes of mystery and magic, a depiction of frontier life, an exploration of relationships, a poetic illustration of the wonder of the Alaskan wilderness, and a fairytale come to life much like our main characters’ lovingly crafted snow girl.

Set in the 1920s in the Alaskan wilderness, Jack and Mabel barely eke out a living on their homestead, their prospects as bleak as the gray winter days. The middle-aged couple escaped the orchards and farmland back East, and the social expectations Mabel, in particular, found suffocating, but losing themselves in their new world of mountains and forests does not mean losing their long held desire to have a child to call their own.

On the first snowfall, the pair decides to make a girl out of snow. They sculpt a delicate face and figure, giving her birch branches for arms and hay for hair, painting lips with crushed cranberries and dressing her with a hat, pair of mittens, and a scarf of dewdrop lace. In the morning she’s gone. Or is she? Jack and Mabel both spot a young girl cavorting around the woods, appearing like a sudden gust of wind off the glacier but tangible enough to leave faint footprints in the snow. Faina, she calls herself, blowing in and out of the couple’s lives every winter, coming with the first snow and disappearing in spring. She becomes like a daughter to the couple, but likeany wild thing, they can’t keep her. Even so, their lives entwine, leaving each other changed.

Not long after Jack’s first sighting, he describes her: “She moved through the forest with the grace of a wild creature. She knew the snow, and it carried her gently. She knew the spruce trees, how to slip among their limbs, and she knew the animals, the fox and the ermine, the moose and songbirds. She knew this land by heart.”

The snow child, who flits between trees with a fox at her heels, is a question who doesn’t have an answer. Is she a snow spirit who comes and goes with the seasons?Is she an orphaned, human girl turned as near wild and untamable as her furry companion? Ivey wisely balances between these two possibilities, ultimately leaving theanswer up to the reader.

Ivey draws upon Russian fairytales, like “The Snow Child” as retold by Freya Littledale and illustrated by Barabara Lavallee, “Russian Lacquer, Legends and Fairytales” by Lucy Maxym, and “Snegurochka” and “Little Daughter of the Snow” from Arthur Ransome’s “Old Peter’s Russian Tales.” Readers don’t have to already be familiar with these stories to know how Ivey’s “The Snow Child” will end; it’s foretold, just as we all know that after winter spring will come.

That’s not the point. At the beginning of the story, Mabel treks across a barely frozen river in hopes of falling through, so focused on the blackwater inches beneath her feet it isn’t until she reaches the other side that she looks up to the alpenglow on the mountain peaks. Later in the story, with Jack and Faina, Mabel goes skating along this same river, the ice solid this time, laughing and playing; at the end, breathless and tired from their fun, the three appreciate the way the moonlight makes the white mountains glow. The point isn’t how we all know the story will end for Faina, just as we know how all of ours will eventually end. It’s about Jack and Mabel realizing their personal winters are not unending. We can all remember in the dark days of winter that spring will always be coming. Sometimes it just takes a child of the snow for us to realize it.

• Clara Miller is the staff writer for the Capital City Weekly.