Anniversaries of major historic events offer unique opportunities to reexamine and challenge our long-held beliefs surrounding those momentous occasions. Sometimes our reflections on the past change because our culture changes, altering the lens through which we view history. However, other times the social, cultural, and political environment of the past has resulted in the obscuring or exaggeration of key aspects of history, creating myths that preservere and gain legitimacy over time. In 2017, as Alaska commemorates the 150th anniversary of the Treaty of Cession, we must once again ask ourselves if what we hold to be true holds up.

For the many Alaskans who could recite this in your sleep, please bear with me. On Oct. 18, 1867 Princess Maria Maksutova stood next to her home in Sitka to bear witness to the formal ceremony that would transfer Alaska from Russia to the United States. Her husband, Prince Dimitrii Maksutov, the Chief Manager of the Russian American Company (RAC), had argued against ceding Alaska to the United States. He failed to convince the RAC and the Tsar, and with the signing of the Alaska Treaty of Cession in March of 1867, the residents of Russian colonies in Alaska had to decide to go or stay and become United States citizens. For those who had grown up in Alaska, going to Russia meant leaving the only home they had ever known. To make matters worse, the Americans attending the ceremony expressed a bit more enthusiasm than may have been perceived appropriate considering the solemn moods of many Russian American Company attendees. As the Russian flag came down over Alaska for the last time, it got stuck. The Russian that finally freed the flag dropped it, and it snagged on Russian soldiers’ bayonets below. As the story goes, the symbolism struck Princess Maksutova to the core and, overcome by emotion, she fainted dead away into the arms of her husband.

The fainting of Princess Maksutova is a beautifully romantic story, filled with sorrow, frustration, and patriotism. This legend has so successfully infiltrated the history books and popular local lore that many no longer question its validity. However, not only do first-hand accounts of the Oct. 18, 1867 Transfer Ceremony in Sitka not support this story, but the Princess’s dramatic faint does not become prevalent in literature until the latter half of the 20th century.

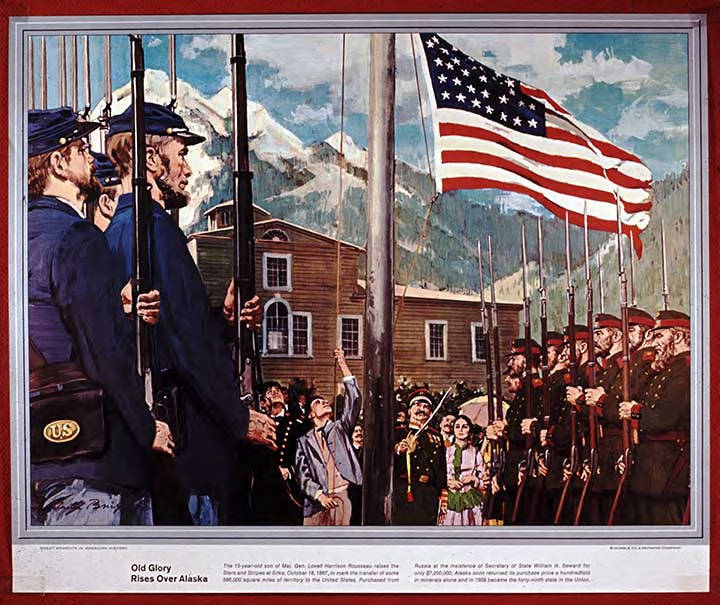

Numerous primary sources exist for the Transfer Ceremony, and while many of these mention that Princess Maksutova wept as the Russian flag was lowered, none mention her fainting. Those sources include Captain George Foster Emmons’ account in the journal of the U.S.S. Ossipee; Andrew Alexander Blair’s diary, kept during his service aboard the U.S.S. Resaca; letters written by Marietta Davis, wife of Major General Jefferson C. Davis, the first military commander of Alaska; the memoirs of T. Ahllund, a Finnish employee of the Russian American Company; the reminiscences of John Kinkead, Alaska’s first Postmaster (1867-69) and the first Governor of the District of Alaska (1884-1885); and the 1867 report of U.S. Army Major General Lovell H. Rousseau to Secretary of State, William H. Seward. Additional first-hand accounts include those of newspaper correspondents that attended the Transfer Ceremony, including journalists from the New York Times and the Daily Alta California. So why did this story take hold so many years after the Transfer? It’s hard to say, but we can turn to these same primary sources for clues.

In his account of events on Oct. 18, 1867, Captain Emmons writes that General Rousseau’s acceptance of the transfer “ended the ceremony–much to the disgust of two newspaper reporters, who were present and expected a spread eagle speech to report to their papers.” While the correspondent for the Daily Alta California tactfully describes the ceremonies as “brief, but impressive,” the reporter for the New York Times merely writes “the transfer was concluded in a purely diplomatic and business-like manner.” Less encumbered by niceties, Marietta Davis best sums it up in a letter to her sister in which she describes the ceremony as “not very imposing.” Even reports of the reception following the ceremony fail to convey excitement. Emmons writes that “officers assembled in the Gov(ernor) Prince Makesoutoff quarters, drunk a glass of Champagne and dispersed.”

In the years following the Alaska Treaty of Cession, a less-than-tantalizing Transfer Ceremony probably posed few difficulties for newspaper reporters or Alaskan residents. Among other problems, the turbulent transition period brought social tensions, economic decline, and the struggle to establish a civil government. Post-Transfer Alaska provided enough news to fill volumes, and it did just that.

As the 20th century got underway, two things began to change that may have refocused attentions on the Transfer Ceremony: the growth of tourism and the push for statehood. Beginning in the late 1800s, tourists began making their way north to explore Alaska. As evidenced by old postcards, photographs, and travel brochures, the opportunity to visit the traces of Russian American provided a large draw, much as it does today. Around the same time, Alaskans formally began to assert their right to statehood. On March 30, 1916, Alaska Congressional Delegate James Wickersham introduced the first bill for statehood. The date was no accident. He proposed that Alaska become the forty-ninth state on the forty-ninth anniversary of the signing of the Treaty of Cession. The very next year, the Territorial Legislature declared Alaska Day, Oct. 18, an official state holiday. As Alaska worked to promote its significance to tourists and the federal government alike, it’s not hard to understand how a lackluster Transfer Ceremony might suddenly have become a problem.

In 2017, Alaska commemorates the 150th anniversary of the Treaty of Cession. So tied is the Treaty and the ceremony that formalized it to our contemporary culture, identity, politics, and economy that it is difficult to imagine this pivotal moment in Alaska’s history as “not very imposing.” A fainting princess adds drama to retellings of the Transfer Ceremony, but it also may have had very applicable economical and political motivations. Maybe someday the first-hand account to support this story will resurface in some long-forgotten archive, or maybe we need look no further than the existing accounts of that day to understand why we seek to aggrandize the past.