Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, Skagway,

In the early morning hours of Sunday, April 3, 1898, the first of a series of snow slides struck the Chilkoot Trail. The trail was one of the main routes to the Klondike gold fields during the great gold rush of 1897-1898. This first slide hit approximately 200 stampeders who were camping at the Scales; 20 were buried beneath the snow. Those who hadn’t been buried quickly shoveled out those who had. Fortunately, there were no fatalities.

The following description of the event is a postscript to a letter written by John Morgan of Emporia, Kansas to his friend Charles Harris, later published in Morgan’s hometown newspaper, The Emporia Gazette. It was the last thing John Morgan ever wrote.

April 3, 1898

Friend Cha [rle] s.: We retired last night, all well and in good shape. About 2 a.m. we were all aroused by our stove pipe falling down and our tent nearly being covered with snow. We all got up and got out in double quick time; to find out we had a snow slide. We put in the rest of [the] night in shoveling snow from tent and around. It has been snowing for five days and is still snowing hard. About five feet of snow has fallen during this storm. No one was killed, only one man getting hurt anyways bad. Several tents were buried under snow, and we had quite a time in getting some out. Had to cut through tents to get them out. We were all in luck once more, not getting even a scratch, or having our things scattered about as some had theirs. Everybody in camp got up and stayed up the rest of the night looking for buried men. Still snowing and no signs of the storm breaking up. Good-bye. Have a chance to send letter to Sheep Camp – Good day. J. M.

As Morgan mentions, the weather of the preceding week had been bad. Spring is a fairly common time for avalanches in the upper regions of the Chilkoot Trail and the months of February and March had seen a great deal of snow. In addition, the first two days of April were accompanied by warm winds from the south. These winds combined with the heavy snow fall made for unstable conditions on the trail, perfect for avalanches.

Those who knew the region well understood what the weather meant and warned others of the risk – Native packers, for example, refused to go above Sheep Camp – but a number of the stampeders, strangers to the mountainous terrain and the dangers that came with it, ignored their words of caution and proceeded to pack their outfits toward the summit. For the most part, these were the unfortunate people swept up in one of the greatest tragedies of the Klondike gold rush – the Palm Sunday Avalanche, or as the Skagway News would put it: “The Death Dealing Snow Slide of the Chilkoot Pass.”

Frank G. Bearse, a companion of John Morgan, lived to regret his decision to camp out at the Scales. In a letter that, like Morgan’s, was published in their hometown Emporia newspaper, Bearse stated:

We moved from Sheep Camp to the Scales, March 27th, and had most of our goods on the summit, but should never have camped at the Scales. We should have gone below and waited until after the storm was over, for it is safe to say that five and a half feet of snow fell on the level in four days.

The 2 a.m. slide at the Scales was merely the first of several over the next 48 hours. At 9:30 a.m. in a different part of the trail, three people were buried by a small avalanche but were dug out alive. A little after 10 a.m. three campers at Profanity Hill (also known as Long Hill) were crushed to death in their tents by another snow slide. An ox by the name of Marc Hanna was buried with them but dug out unharmed. He was soon put to work hauling the bodies of more slide victims to Dyea. At around the same time, men who had been sent to work on the Chilkoot Railroad & Transport Company’s new aerial tramway started the descent back to their camp near Stone House, where cook Floyd M. Hunt was waiting for them with a generous lunch. At some point between 10 and 11 a.m., the tramway workers wandered off the trail into a ravine, probably due to the very poor visibility caused by the heavy snow and wild winds. This ravine is actually the current recreational trail. The entire party was buried and crushed to death by a slide. Their bodies were not found until the next day, when a man discovered a corpse while attempting to dig out his outfit.

The campers at the Scales evacuated the area between 10:45 and 11 a.m. Armed only with shovels, they marched in a single line, clutching a 200 foot long rope. The strongest men of the group, those who knew the trail the best, led the rest, following the snowy footprints of the ill-fated construction crew. Shortly before noon the party entered the same ravine and almost immediately a third of them were buried up to 50 feet by another avalanche, the fifth that day. Among them was the unfortunate John Morgan, who only hours before had written of his early-morning encounter with the first snow slide of the day at the Scales. Those in the rear of the line were left nearly untouched and a few hurried on to Sheep Camp to raise the alarm.

The stampeders in Sheep Camp heard the thundering of the slides, but until the witnesses arrived, no one knew to be more that vaguely alarmed. Guns were fired to summon help and within the hour around 1500 stampeders had made their way to the site of the tragedy. When the rescue team first arrived, they made efforts to find and dig out those who were still calling out, but as time passed the snow beneath their feet grew silent.

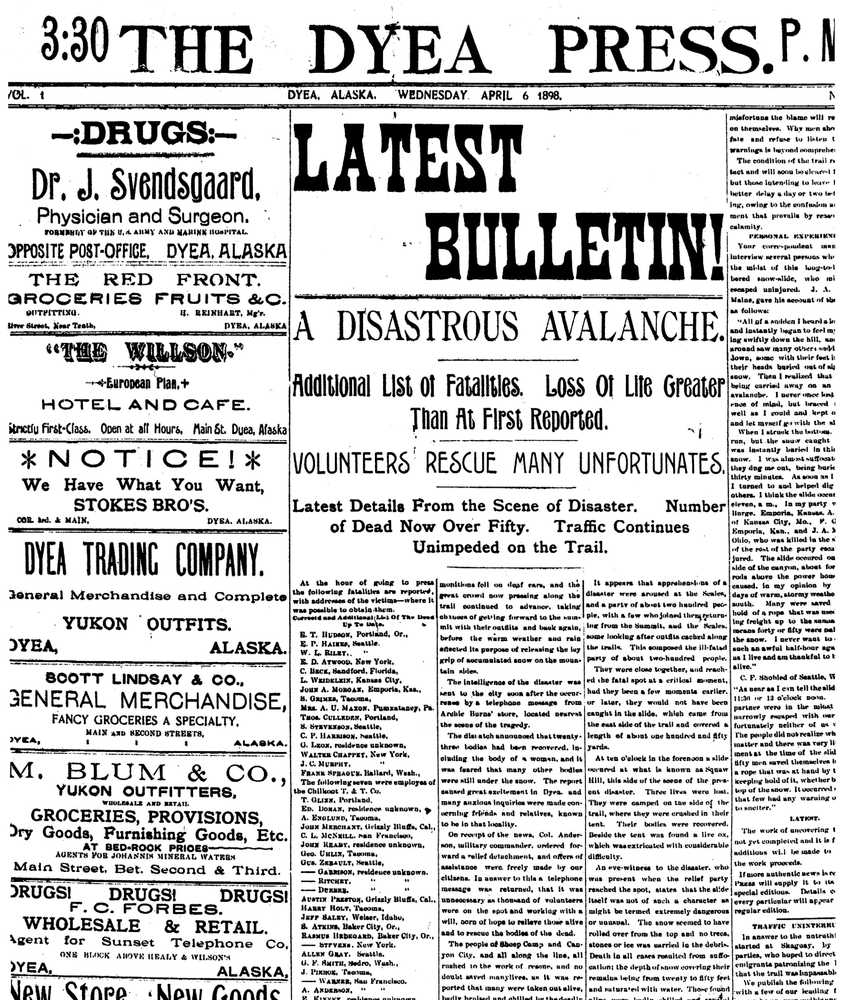

News of the avalanche spread, rapidly aided in large part by the telephone lines that had been erected along the trail back in November 1897. “The intelligence of the disaster was sent to the city [Dyea] soon after the occurrence by a telephone message from Archie Burns’ store, located nearest the scene of the tragedy,” said the April 4 issue of the Dyea Press. Archie Burns’ store was probably located at the Scales and may have been associated with his surface tramway operating from there to the Summit, although there was also a telephone located in the Alaska Railroad & Transportation Company’s engine house on Long Hill, a building that served as a temporary morgue during the disaster.

Estimates of the number of people saved in those first hours vary widely, ranging from two to 100, but they were really closer to 10, though four of those 10 are known to have died of exposure following their extraction from the snow. Volunteers dug for survivors and then bodies for a total of four days. During that time, traffic over the trail was halted as stampeders temporarily abandoned their trek to help locate the victims. William Pickard Hainesworth spoke of the men from Sheep Camp who went to help despite the threat of another slide (and there was certainly still a threat, because another slide on Monday, April 4, killed two more people camping along the trail). Hainesworth wrote, “When we came here we were told that it was every man for himself and that if a man was lying beside the road with a broken leg no one would help him, but I am glad to find it is not so.”

Estimates of the dead are even less certain than those of the rescued. A committee was formed to release death certificates, but they were either never completed or lost. Newspapers, in the great fervor that arose in the wake of the tragedy, published competing lists. Interestingly, there are few names that appear on more than one of the lists and at least one man listed had died six months previous. One surprisingly unreliable list is that of the names on the headboards at the Slide Cemetery in Dyea, established for the avalanche victims by Colonel Thomas M. Anderson, Commanding Officer of Companies B & H, 14th Infantry, U.S. army, stationed in Dyea. Bodies of victims claimed by friends or relatives were shipped “Outside” to be buried, while others were sent to Dyea to be buried in the Slide Cemetery. Still others may have been buried at a small cemetery in Sheep Camp. John Morgan’s body and letter were sent home to Kansas by his friend Frank Bearse (who survived, although buried in the same avalanche that killed Morgan), yet Morgan’s name still appears on one of the headboards in Dyea. At least one of those killed was a woman, a Mrs. Anna V. Maxson. She had already been buried in the first slide and when the camp evacuated she made her way to the front of the line, saying that one time was enough to be buried alive and that she was getting out of there as soon as possible. She was survived by her husband, who was walking at the back of the line.

A conservative estimate of the total number of dead is around 60 to 65. Ironically, all the people at the Scales probably would have survived had they not evacuated when they did.

The site of the great avalanche along the Chilkoot Trail is unmarked, but the current recreational trail goes right through the avalanche path. Today the Slide Cemetery in Dyea is the major existing landmark for the Palm Sunday Avalanche victims. At last count there are some 40 headboards in the cemetery. Five have gone missing since an earlier count in the 1980s, and of those that remain all are in poor shape. The cemetery is visited by thousands of tourists every summer.

Information for this article is from the diary of William Pickard Hainesworth, a letter by Chilkoot Railroad & Transport Company cook Floyd M. Hunt, a letter by Frank G. Bearse published in the Emporia Republican of April 21, 1898, a letter by John Morgan published in the Emporia Gazette of April 24, 1898 and an article on the tragedy published in the Dyea Press of April 4, 1898. Madison Heslop was a volunteer at Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park during the summer of 2011. Frank Norris was a seasonal historian at the park from 1983-1988. Karl Gurcke is the current park historian.

This article and many others were first run on KHNS, Haines’ public radio station, through the station and the Sheldon Museum’s 15-minute History Talk program.