Walter Harper, who is buried beside his bride Frances Wells in Juneau’s Evergreen Cemetery, lived a brief and wondrous life. He was born in 1893 to Arthur Harper, dubbed the father of the Klondike, and Seentahna, a Koyukon Athabascan woman. Arthur died of tuberculosis in an Arizona sanatorium, leaving Walter with no memories of his father. The child grew up Athabascan, and did not begin learning English until he was a teenager at the St. Mark mission at Nenana. There, the Episcopalian Archdeacon Hudson Stuck recognized in him something special, and hired Harper as a guide and interpreter. Their relationship deepened until Stuck came to consider Harper a son. They traveled thousands upon thousands of miles across Alaska by dog sled and boat. They, along with Robert Tatum and Harry Karstens, were the first to reach the summit of Denali. In the last year of Walter’s life, the two made an even more daunting six-month winter circuit from Fort Yukon to Kotzebue, then along the coast to Herschel Island and back to Fort Yukon. When Walter Harper and the 352 other people aboard the Princess Sophia perished later that year, Hudson Stuck lost both a son and his vision of what he hoped Alaska could become. Alaska lost something equally devastating, though less tangible.

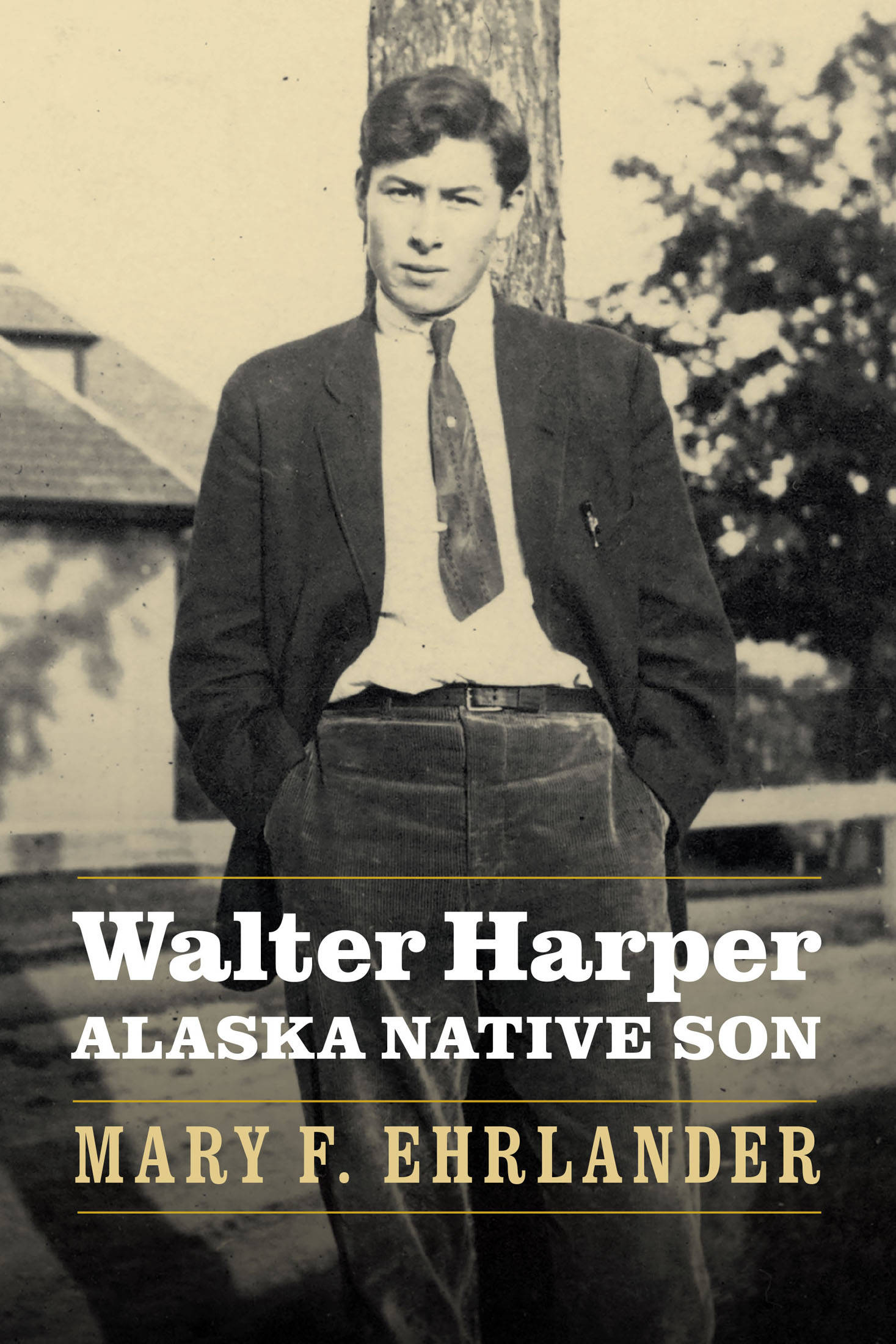

Harper’s unfinished life haunts me almost as much as the amazing things he did in his 25 years. I used to lose sleep over the fact that no one had published a comprehensive biography of him, worried that this exceptional person would only become increasingly forgotten with each passing year. That changed this winter, when I received an advance copy of Mary F. Ehrlander’s “Walter Harper, Alaska Native Son.” Ehrlander, the director of Arctic and Northern Studies and a professor of history at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, offers a solid and fascinating historical foundation for understanding Harper. The book is incredibly well researched, accessible and poignant. It reads like a labor of love — and I mean a heck of a lot of labor. I can only imagine the amount of time Ehrlander spent digging through buried documents and connecting all the dots to create this wonderful portrayal. It quickly became apparent that I wasn’t the only one who’d lost sleep over wanting Harper’s story to be more fully told.

Ehrlander records many, often subtle, anecdotes to bring Harper to life. She describes a childhood pranks he enjoyed playing:

“His favorite stunt was to startle people who were sleeping in open tents. He and his friends would tie a tough piece of dried fish to a strip of caribou sinew and slip the other end over the toe of the sleeper. Before long a dog would greedily swallow the fish and awaken the person, causing a commotion.”

Another story, which exemplifies his good humor in the face of adversity, is of Stuck and Harper. They had been mushing for days along the Arctic coast in heavy winds with the ambient temperature never rising above negative forty. Harper’s journal entry only reads “some cold for the fifth of April.”

There’s multiple tales of Stuck and Harper dropping everything they were doing to try to save the lives of sick or wounded people — often racing through wilderness in less than ideal situations to do so. There’s the story of Harper’s dream of hunting a polar bear and the folly that results. There’s the bit about Walter teasing his sister not to worry, that he still loved her, as he prepared to marry Frances, a nurse working at Fort Yukon. There’s a multitude of other stories, which left me with a much better perspective and appreciation of Harper.

The photographs, many of which I hadn’t seen before, add greatly to the narrative. Whether it’s an image of Harper carrying a small, smiling boy at St. Marks, Stuck and Harper climbing Denali, or a beautiful portrait of Frances Wells, they’re immediate, moving and haunting. The last image of Harper is particularly wrenching — you see him sitting in a skiff, wearing a suit and smiling with unadulterated joy. He and Stuck had just finished their six-month winter Arctic circuit and summer of river travel visiting villages. He is about to be married and go east to study to become a missionary doctor, with the plan to return to serve his people. I don’t think I’ll ever forget that picture. A few months after it was taken, the Princess Sophia went down.

Alaskans owe Mary F. Ehrlander thanks for helping keep Harper’s story and legacy alive. This is an important book, one I would highly recommend to anyone interested in Alaskan history or an inspirational and visionary human being.

• Bjorn Dihle is a Juneau writer. His first book is “Haunted Inside Passage: Ghosts, Legends and Mysteries of Southeast Alaska.” You can contact or follow him at facebook.com/BjornDihleauthor.