Down the street from our Douglas Island home is a popular spot for runners and after work strollers. The forested Treadwell historic trail runs along Gastineau Channel across from downtown Juneau. The trees along the trail are the resilient alder that grow in the aftermath of glacial recession, or in this case, an earthen nervous breakdown.

If you look straight ahead as you make your way along the dirt, you might miss what’s along side-crumbling cinder blocks covered with green moss, gnarled rusty train tracks, steel poles marking off the fence around what were tennis courts, hollowed out buildings fading into the recesses of time.

You are walking through what was the biggest and most profitable hard rock gold mining operation in the world. What strikes me about the ruins down the street is that unlike ancient Rome or Greece or Egypt, the past they represent was not that long ago.

The Treadwell Mines and company town were founded and established by John Treadwell, a carpenter and prospector from San Francisco. He bought his first Treadwell claim for $400. From 1882 to 1922, the mines employed up to 2000 miners from 17 countries and ran 24 hours a day, seven days a week, except Fourth of July and Christmas.

The company paid employees well and provided a community that in its heyday had an indoor swimming pool, Turkish baths, sauna, and a department store that brought in the finest toys and gifts from San Francisco. Off-shift, miners, supervisors and their families played on football, baseball and basketball teams. They visited the Treadwell Club, with billiards, dancing, and movies. It even had a special room for writing letters and reading.

I imagine the wife of a hoist operator in that room, musing on her first impressions of Treadwell when she arrived on a steamship from Washington state in January, 1913. She wrote, “I thought I had never heard so much noise going on when we reached the street. I heard this great roar and was told it was the stamp mills which never stopped day or night, year in and out.”

[Douglas marks 100-year anniversary of the Treadwell Mine cave-in]

“I’ll never forget the next morning when daylight came and I looked out across Gastineau Channel and saw the white mountains looming up. It seemed they were just at my feet. It was breathtaking and frightening all at once.”

The unsigned “A Treadwell Wife Remembers” is published in the bible of Southeast Alaskan mining history, “Hard Rock Gold,” by the late David Stone. Stone died suddenly of a heart attack at the age of 55 in 2012, four years after the Treadwell Historic Preservation and Restoration Society got started.

“David left too early,” laments my Douglas neighbor Paulette Simpson, a society member. For going on a decade, Simpson and a small but determined group have been stepping towards their goal of turning the area into an historic park. They’ve erected colorful, descriptive signs with period photos, restored the shell of an iconic pump house at the end of what was the biggest deep water port in Alaska, and are now raising money and restoring the only still intact office building.

On a recent sunny Monday evening, Simpson met me for walk along the trail. “This is the best time of year to see what’s left,” she noted. “After the snows melt and before the summer overgrowth.”

Simpson bubbles with tales of the bygone era of industrial romance and company town amenities. Between the mine’s financial success, the several period newspapers in Douglas and Juneau, and the many preserved and archived photographs, the story of Treadwell “is all there,” says Simpson. “It’s just a matter of taking the time.”

The historic trail is parallel to Sandy Beach. Parts of machines that ran the mines and broken dishes from the dining hall emerge from the sand at low tide. The most coveted place for dog walkers in Douglas is not really sandy at all; it’s the result of 80 acres of mine tailings. Over the course of four decades the Treadwell Mines crushed a world record 26 million tons of rock and produced 70 million dollars in gold.

In 2010 University of Alaska Press published Treadwell Gold, by Sheila Kelly, the most complete account and only book about life in Treadwell. The book was the culmination of decades of research inspired by family history. Her father was born in Treadwell in 1899, and her grandfather was the mine machinist.

[Demise of world’s largest gold mine helped build Juneau]

A retired environmental educator, the Seattle resident says she was at first more interested in the daily life of the residents than in the mining. In writing the book, she learned there was no denying the Treadwell mines put Southeast Alaska on the world map.

She also learned that the Tlingit people who lived in the village adjacent to Treadwell had been in the area for at least 9000 years. Several Tlingit people worked in the mines. However, as Kelly writes, “The Tlingit did not understand the excitement and greed that gold set off in white men who were coming into the area. Hunting was the Native’s primary occupation, and they found gold a poor substitute for lead bullets.”

Kelly was in town recently to consult on a play based on her book by Perseverance Theater.

“Treadwell is a great story. And I felt I had both a privilege and responsibility to pull it together. I wanted to bring the town alive,” she said.

When Kelly’s father was boy, he could get a fresh California orange or his shoes repaired at the company store, remembered as the largest and most well stocked merchandiser in Alaska.

To get a drink or deposit their pay, mining families had to go next door to Douglas, which among the usual amenities, had bars, churches, and a hospital.

Today’s Douglas has a bar, pizza place, burger joint, library, post office, car repair, hair salon, regional theatre, costume shop and a handful of gas pumps.

But what I’d give for it to have a grocery store with fresh produce, let alone a place to re-sole my favorite boots …

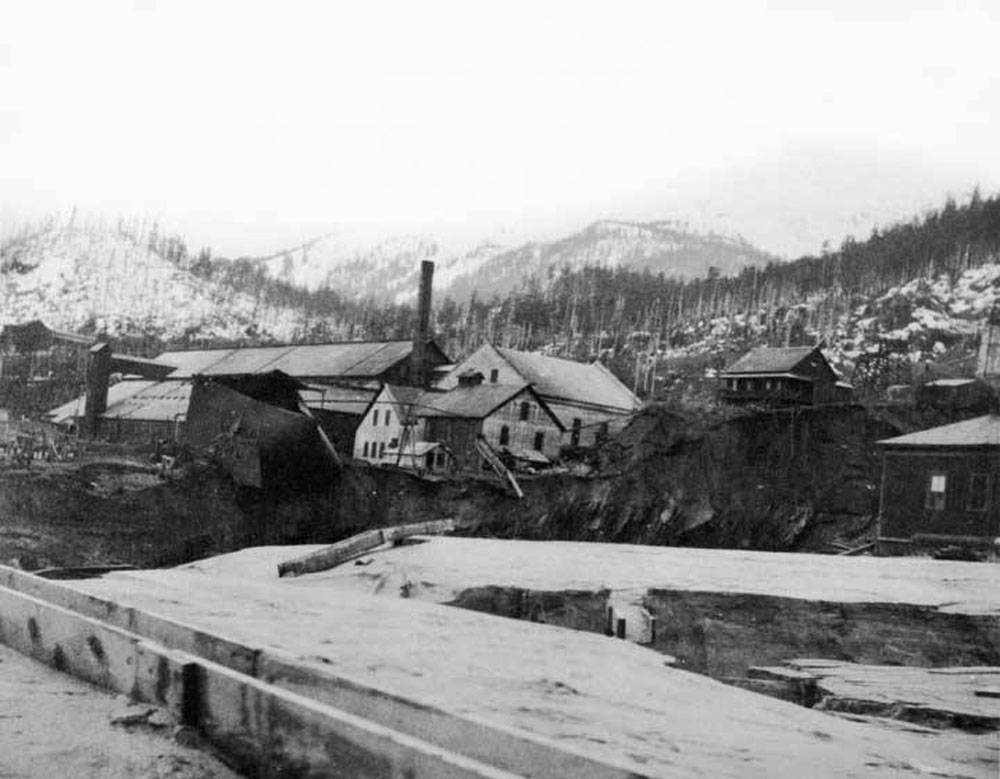

The Treadwell mines and company town came to a spectacular end April 21, 1917, when a massive cave in flooded three of four underground mines, 2,300 feet deep. They’d yielded 10 million tons of ore. The void was filled with an estimated three million tons of seawater. Failure of unstable underground rock pillars and extreme high tide led to the collapse.

In the days preceding the disaster, the earth gave enough signals that all but one of the miners escaped being a victim. (Though his death was disputed, and the mine’s official stance was that he had left town, a jury found in favor of the man’s wife and awarded her damages. Some sources even today, however, still claim no one died.)

The day prior to the collapse was ladies day at the swimming tank, when, as Kelly writes, “the water in the tank was sucked out in one great whooshing gulp through a crack that opened up in a corner of the pool.”

On Friday, April 21 at 5:30 p.m. is an open gathering at the site. Attendees may read passages from Kelly’s chapter on the cave-in.

Mine geologist Livingston Wenecke rushed to the site, inched his way out on the tram trestle that was precariously strung over the hole, and shone a light down into the widening cauldron. He watched a mass of mud and water, accumulate and then slide away with a deep rumble. As the muck was gulped down, the lower regions underground belched a blast of air that had the musty odor of the deep reaches of the mine.

“The drama of the cave-in was that the town and the people lived right on top of the mines,” said Kelly.

This weekend there are two more events to mark the 100th anniversary of the cave-in.

Saturday, April 22 is The Treadwell Miners’ Ball at the Baranof Hotel in Juneau. It’s $50 per person and runs from 7-11 pm. Tickets and information are at www.treadwellsociety.com

Sunday, April 23 are walking tours and a potluck picnic at the Sandy Beach Log shelter from 2-5 p.m.

Culminating a series of 100-year anniversary events is the performance of the play, which centers on the story of the cave-in. It takes place between July 4, 1916 and July 4, 1917, and will be performed at the end of June through July 4th, 2017.

See a complete list of 100th anniversary events at www.treadwellsociety.com.

Katie Bausler is a freelance writer and an enamored resident of the island kingdom of Douglas, Alaska.

Correction: An earlier version of this article erroneously stated that David Stone died in 2008. He died in in 2012. The article has been updated to reflect the change. The Capital City Weekly regrets the error.