The University of Alaska Southeast kicked off Native American Heritage Month a couple days early with its most recent Evening at Egan lecture Friday night.

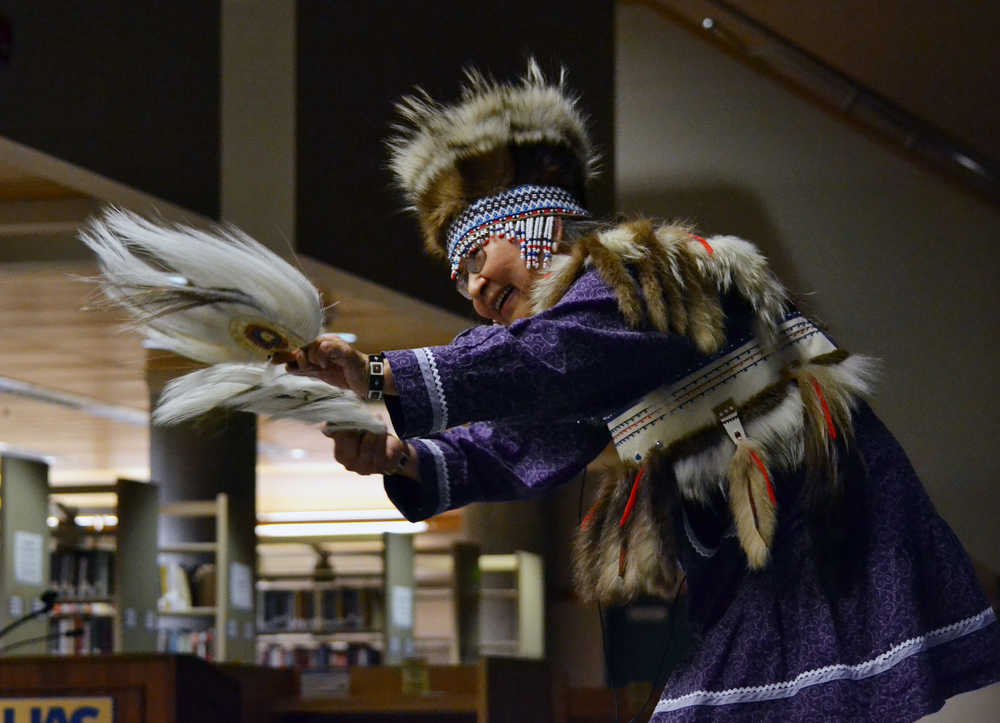

Theresa Arevgaq John, a professor of cross-cultural studies at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, spoke, sung and danced during her lecture in Egan Library. Dressed in traditional Yup’ik garb, she painted the picture of a life spent straddling two cultures, one Native and the other Western.

John grew up in the Yup’ik village of Toksook Bay, about 100 miles west of Bethel. She was born into an age of transition. John’s was the first home in her village to have an electric generator. Growing up, several of her neighbors still lived in traditional mud houses.

But the biggest changes affecting John and the rest of Toksook’s Bay’s residents during that time weren’t technological, they were cultural, John told a crowd of about 70 people Friday night.

“I was the first generation to be exposed to English,” she said. “I was the first generation to be exposed to Western schooling.”

As Western missionaries spread into the more remote regions of Alaska during the last century, they brought with them a culture foreign to John and her family. John’s grandfather was among the first people in his village to be given a Christian name, a process that often had its roots in the general store, John said.

Traveling priests would give people biblical first names. John’s grandfather, for instance, was named John after Saint John. (Theresa John’s English name came from Saint Theresa.) Surnames were a different story. They were often assigned randomly based on items priests happened to encounter at the general store.

Coffee and Green — after green beans — were commonly assigned last names, John recounted.

Long before she went on to earn her bachelor’s, master’s and doctoral degrees from UAF, she was subjected to Western education in a Bureau of Indian Affairs school in her village. There she often got in trouble for reasons she didn’t understand at the time.

“I wasn’t misbehaving. I wasn’t doing anything wrong,” she said.

Looking back, she realizes that the reason she was being punished was for speaking Central Yup’ik, instead of English, which was required at all times. Because John was of the first generation in her family to learn English, she was only subjected to the language in school, where they learned from reading books such as “Dick and Jane.”

Living between two cultures often proved difficult, according to John.

“The culture of the school was very disconnected from the culture of the village,” she said. “I never told my parents what I was learning in school because it had no relevance to them. It had no importance.”

As she grew, her grandmother taught her to appreciate the fact that she was among the first people Toksook Bay to have to adapt to a new culture, to blend the new ways with the old.

Her grandmother told her Western schooling would allow her to know “more than one life.” It positioned her to learn how to share the world with people of other cultures.

“It was a big challenge, but it was a good challenge,” John said.

• Contact reporter Sam DeGrave at 523-2279 or sam.degrave@juneauempire.com.