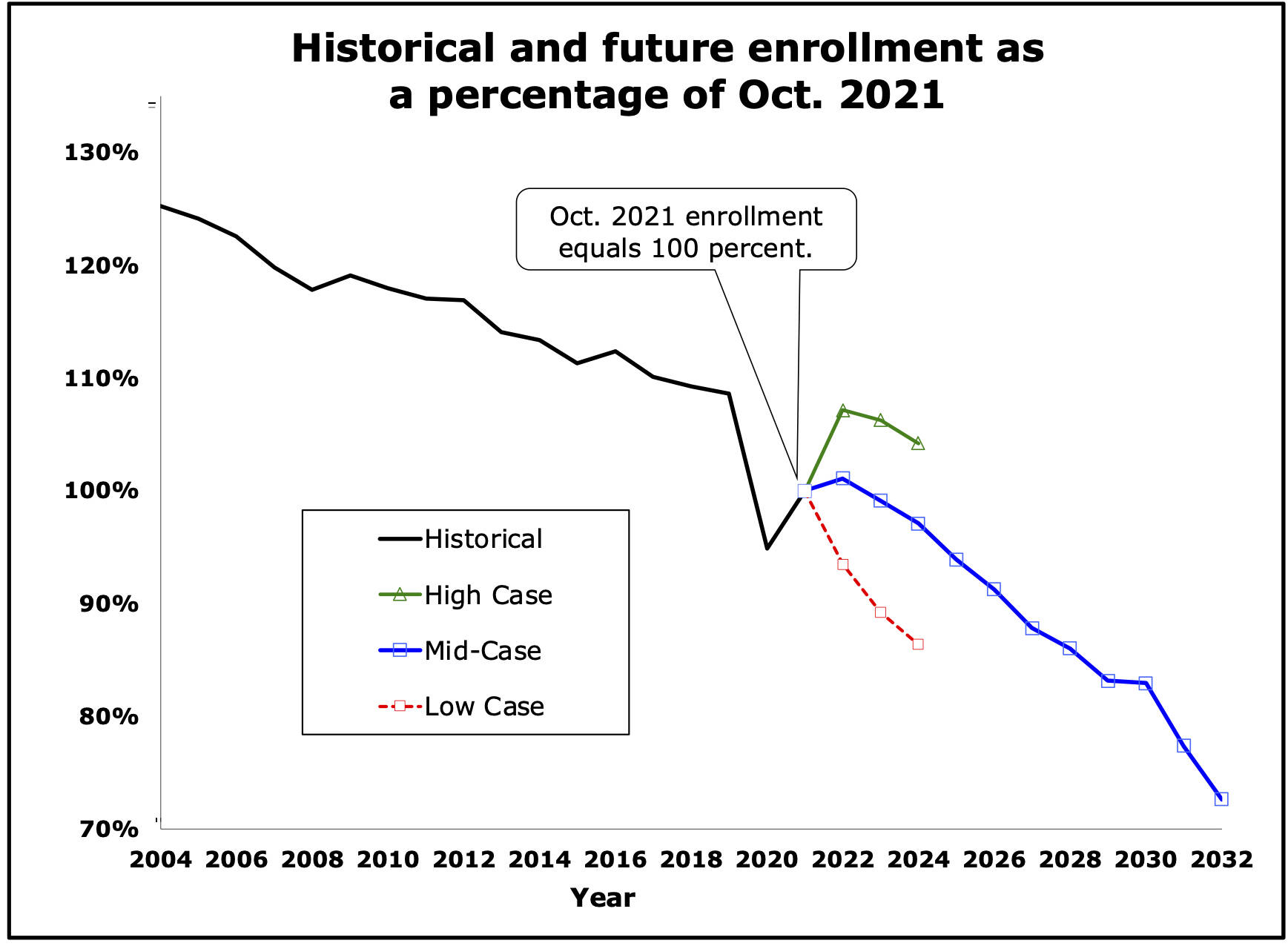

It’s a tricky math problem: There were 5,701 students in Juneau’s schools in 1999, there’s 4,223 expected this year and the “mid-range” forecast is 3,036 in 2032.

The problem isn’t calculating the drop’s percentage (46.7%), but what it means in terms of the numbers in dollars city leaders are willing to spend on school maintenance, upgrades and other projects in the years ahead. And if subtraction should be part of the equation by, for instance, closing a school.

Right now, there’s considerable disagreement about the correct answer.

The update in Juneau’s long-term student decline, based on new census figures, is detailed in a report by Erickson and Associates discussed by the Joint Assembly School Board Facility Planning Committee during a midday webinar Thursday. The report attributes the drop primarily to declining birth rates — including a 12% drop from 2018 to 2019 and another 6% drop in 2020 — reflecting a nationwide drop for more than a decade that “is likely to persist.”

[State reports small population growth, slight decline for Juneau]

“I think from a community standpoint it’s depressing news looking at our school age population,” City Manager Rorie Watt said during an introductory presentation to the committee.

The largest projected decline is elementary school students, from 1,860 this year to 1,197 in 2032. Middle school enrollment is expected to drop from 1,012 to 734 and high school enrollment from 1,353 to 1,104.

One caveat is there’s an enormous gap between the “high” and “low” scenarios for future student numbers – and thus considerable uncertainty about the total a decade from now – but the Erickson report only offers the full range of predictions through 2024. Total student enrollment that year is forecast at a high of 4,353, mid-range of 4,057 and low of 3,611.

The report notes the error rate for mid-range projections since 2009 has been between 0.1% and 3.6%, except for a 13.5% rate during the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 — whereas high and low scenarios are more prone to inaccuracies.

In a letter sent to committee members before the meeting, Watt stated the updated figures shouldn’t strongly affect current operation/delivery of education since “the population changes are happening year by year and the (school district) adjusts its operations accordingly.” But it is timely to discuss impacts regarding capital projects.

“Both Marie Drake and Mendenhall River continue to age,” he wrote. “If the projections are accurate, and there is not much reason to doubt them, then it is more appropriate to add potential school closure into the mix of the discussion about facility renovations. This will be a difficult topic to discuss.”

School board members participating in Thursday’s meeting largely favored keeping schools open and projects continuing, while some assembly members were considerably less inclined to support large commitments.

“We do have these buildings that need major maintenance, and I don’t know if we can afford to not renovate them thinking in eight to 10 years we might not need them,” School Board President Ebett Siddon said.

Mayor Beth Weldon said the option of consolidating schools needs to be a future consideration and in the meantime the school district needs to think on a smaller scale when submitting its wish list of projects. That means a proposed $37 million overhaul of the Marie Drake Building “is not something I’m too interested in,” but a $6 million boiler project “is more doable.”

“We ask for a priority list and every time we get a priority list Marie Drake’s at the top with a huge price tag,” she said. “I think smaller projects are probably where we’re at right now.

Average funding for school projects during the past five years has been 1.8% of “replacement value,” slightly below the industry standard of 2-6%, according to Katie Koester, the city’s engineering and public works director. For school board and assembly members that creates a dilemma where the list and cost of deferred projects continues to increase, but available funds are insufficient without asking voters to approve additional taxes or bonds.

Emil Mackey, the school board’s clerk, said he’s not opposed to consolidation, “but I’m also somebody who’s willing to step back and say I’m not sure there are savings there.” He said there’s also the politically sensitive question of which community — such as Douglas residents or one with a large high-risk student population — will feel shunned if a school closure occurs.

“A parent that has to drive by one school to get their kid to another school, or (have the student) take a bus to school, is not going to be a popular decision,” he said.

Meanwhile, students are going to keep going to existing schools for at least the next five years so “it would be great if we can get everyone more comfortable with reasonable investments we can make until we make longer term decisions,” said Brian Holst, the school board’s vice president. At the same time, officials should evaluate alternative uses of the buildings such as pre-kindergarten programs that are already occurring.

“If we have fewer students it may not be that the conclusion is having fewer buildings,” he said.

Another consideration is the neglect in maintenance spending isn’t just the fault of local policymakers, Mackey said.

“The reason we’ve accumulated this so quickly is over the past decade the state has neglected their responsibility,” he said.

• Contact Reporter Mark Sabbatini at Mark.Sabbatini@juneauempire.com.