When you are a young boy growing up in Brooklyn in the 1930s, sniffing warm pastries your father has placed in the window of his bakery, it is impossible to say what your legacy will be. There is a good chance you will become a baker.

But if you have a taste for the unknown, you might be attracted to the faraway territory of Alaska. There, during a long life, you might leave behind a few stories.

About 75 years ago, George Argus hitched a ride from New York City to Alaska, where he found a job in Anchorage working for the Alaska Railroad. From then until to his death on Oct. 21, 2022 at age 93, George Argus whittled a few marks into the framework of Alaska.

One notch firmly cut into Alaska mountaineering lore was the week Argus spent as “the most isolated human being in North America” in a tent high on Denali. There, he was immobile on his back with a dislocated hip, awaiting rescue from his friends.

Another mark left was the scientific curiosity that led him to become an expert on one of Alaska’s most important plants — especially for moose, caribou, hares and lynx — the willow.

Argus was not born in Alaska and he did not die in Alaska. He became a citizen of Canada in the 1970s and lived most of his life in Ontario. But he experienced Alaska during the prime of his life.

The mountaineering tale happened in 1954. Argus, who had held a few jobs in Fairbanks and on the Juneau Ice Field, was drafted into the Army. He was able to choose his duty station after a while. He chose Delta Junction. He became a climbing instructor there at the Army Arctic Training Center near Black Rapids Glacier.

Elton Thayer, a 27-year-old ranger at Denali National Park, asked Argus to be part of a four-man team that would attempt to climb North America’s highest peak via a route that had not been tried before. Argus said yes.

That April, Les Viereck (24), Argus (25), Morton Wood (30) and Thayer began their ascent of Denali by stepping into the willows off an Alaska Railroad car at Curry. During the next few weeks, they made it up to the roof of North America with much difficulty via the South Buttress. And, as sometimes happens, their big problem came on the way down.

The four men were on top of a steep ridge of snow and ice, pondering how to descend.

In a 2011 interview with Karen Brewster, Argus remembered seeing Thayer’s crampon had slipped off, to the side of his mukluk. A second later he saw Thayer step, slip, then fall.

The remaining three climbers, all attached to Thayer by a rope, dropped to the snow, falling to the tips of their ice axes as the rope whistled by.

Thayer’s momentum yanked them all off the slope. Argus remembered cartwheeling down the wall until his head hit ice, knocking him unconscious.

When the terrain leveled after their 800-foot fall, Thayer was dead. Argus had a dislocated hip and damaged kneecap. Viereck was hurt but functional. Wood was miraculously unscathed.

After tending to Thayer and realizing they could not help him, Wood found some of their gear and pitched their three-man tent. He and Viereck dragged Argus inside.

They made Argus as comfortable as possible in the tent, setting him up with a stove to melt water and a week’s worth of food. Sensing that no one would come to rescue him, Wood and Viereck left Argus without saying goodbye, perhaps because they couldn’t bear the finality.

“All of a sudden, it became quiet,” Argus remembered.

His friends made the arduous trip to civilization and got help.

Finally, young men Argus knew from the mountaineering club at the university in Fairbanks reached the tent high on the mountain. It had been seven days since Argus had seen anyone.

“I offered to put on tea for them,” said Argus. He later said that his trust in his friends prevented him from being scared during the ordeal.

The rescue team sledded Argus out. In time, he recovered from his injuries. A feature on the mountain was named Thayer Basin for Elton Thayer.

Argus executed no more harrowing mountaineering trips. He went on to become a botanist fascinated with the minutia of willow shrubs and trees.

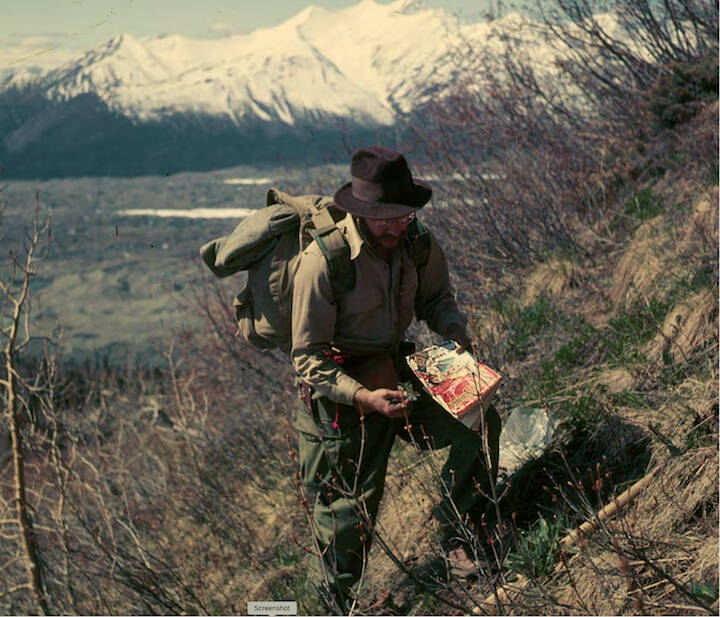

He had collected willows from nunataks (mountaintops that poke through the ice) on the Juneau Ice Field before his Denali trip. He later collected and studied the plants from Ketchikan to Barrow, squinting at details of the far-north plant, the leaves and buds of which sustain moose in summer and winter.

Argus was fascinated with how the hardy shoots of willow came in so many varieties in Alaska (about 40) and how many of those species could interbreed and hybridize, making identification even more of a challenge.

His first publication was the Willows of Wyoming in 1957, which is where he had done graduate work. In 1961, he moved to Canada. There, at the University of Saskatchewan, he studied the willows of Alaska and the Yukon territory.

He executed fieldwork on willows all over North America and central Siberia, often taking along another part of his legacy — his wife Mary and their five children.

He retired from his final professional position at the Canadian Museum of Nature in Ottawa in 1995. After that, he came back to lead willow-related field trips in Anchorage, Fairbanks and other parts of Alaska. Sometimes, when the white molar of Denali was visible on the horizon, he would lift his gaze from the bushes and stare at the mountain. He was the last survivor of that 1954 climb.

• Since the late 1970s, the University of Alaska Fairbanks’ Geophysical Institute has provided this column free in cooperation with the UAF research community. Ned Rozell, ned.rozell@alaska.edu, is a science writer for the Geophysical Institute.