By Ned Rozell

I just so happened to be stretched out on good ol’ Mother Earth the other night when an earthquake happened.

On a Memorial Day overnight canoe trip, a friend and I had dragged our boats onto the gravel of a little island on the Chena River.

After mosquitoes chased us into our tents and we’d all fallen asleep, my dog and I woke to the sound of splashes. A moose strolled by upriver, right past the tent. A few moments later, the ground swayed as if we were strung in a hammock.

During that earthen wave, I looked outside through the screen and saw a young willow, skinny as a whip and belt high. It quivered, the local expression of an underground release 400 miles away from our island and 25 miles beneath the ground surface.

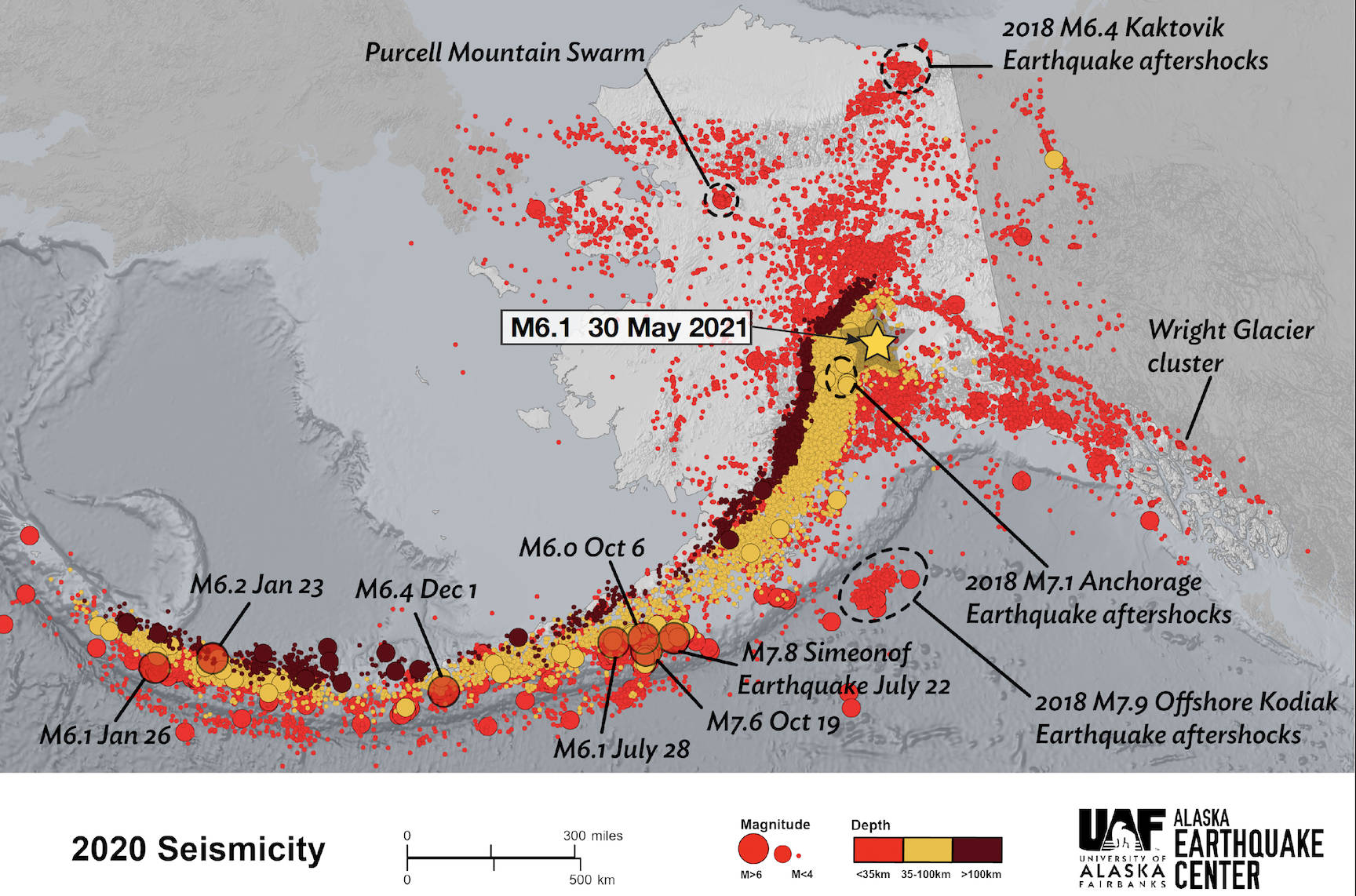

That spot, just east of Talkeetna, was the epicenter of a magnitude 6.1 earthquake felt over much of Alaska.

On the Alaska Earthquake Center’s website, someone reported feeling the shake in Circle on the Yukon River, 270 miles away from Talkeetna. People also mentioned feeling the earthquake in Kotzebue, 530 miles away, as well as Unalaska Island, 900 miles away.

Though it was the highlight of my weekend, earthquakes happen all the time in Alaska. Technicians at the earthquake center, using devices buried all over the state, record an earthquake about every 15 minutes. In one recent year, they detected 54,000 earthquakes. That’s about 150 per day.

Why so many?

Many of Alaska’s earthquakes are the result of immense sheets of our planet grinding past one another, in fits and starts.

The Pacific Plate is the underwater landmass that includes the seafloor of the entire Pacific Ocean. Due to the oozing of molten rock within the center of the planet, that colossus creeps at the speed fingernails grow toward mainland Alaska, which sits on what seismologists call the North American Plate.

Beneath the southern coast of Alaska, the dense oceanic rocks of the Pacific Plate plunge beneath the lighter rocks of the North American Plate.

Giant earthquakes can happen at this plate boundary if the masses release their stuttering grip somewhat close to the ground surface. An example of this was the magnitude 9.2 earthquake epicentered in Prince William Sound in 1964. The rupture happened just 15 miles beneath the ocean floor.

The motion of the Pacific Plate has molded the face of Alaska, giving rise to mountains as well as pulling apart river valleys. As plate motion kneads the landmass of this giant peninsula, sometimes sutures across Alaska’s skin help relieve the stress.

One of these slices in the state is the Denali Fault, the trace of which is visible from satellite within a frown of Alaska Range mountains in the center of the state. Within that arc is a trench, often filled with glacier ice, where many earthquakes happen. Part of the Denali Fault slipped in 2002 to rattle us with a 7.9 earthquake.

Of the 6.1 earthquake many Alaskans felt the other night, State Seismologist Mike West said it was “not a surprise in the least.” But it was interesting enough to him that he wrote a detailed report on it, concluding that “like most earthquakes, there is something to learn here if we are willing to pay attention.”

• Since the late 1970s, the University of Alaska Fairbanks’ Geophysical Institute has provided this column free in cooperation with the UAF research community. Ned Rozell ned.rozell@alaska.edu is a science writer for the Geophysical Institute.