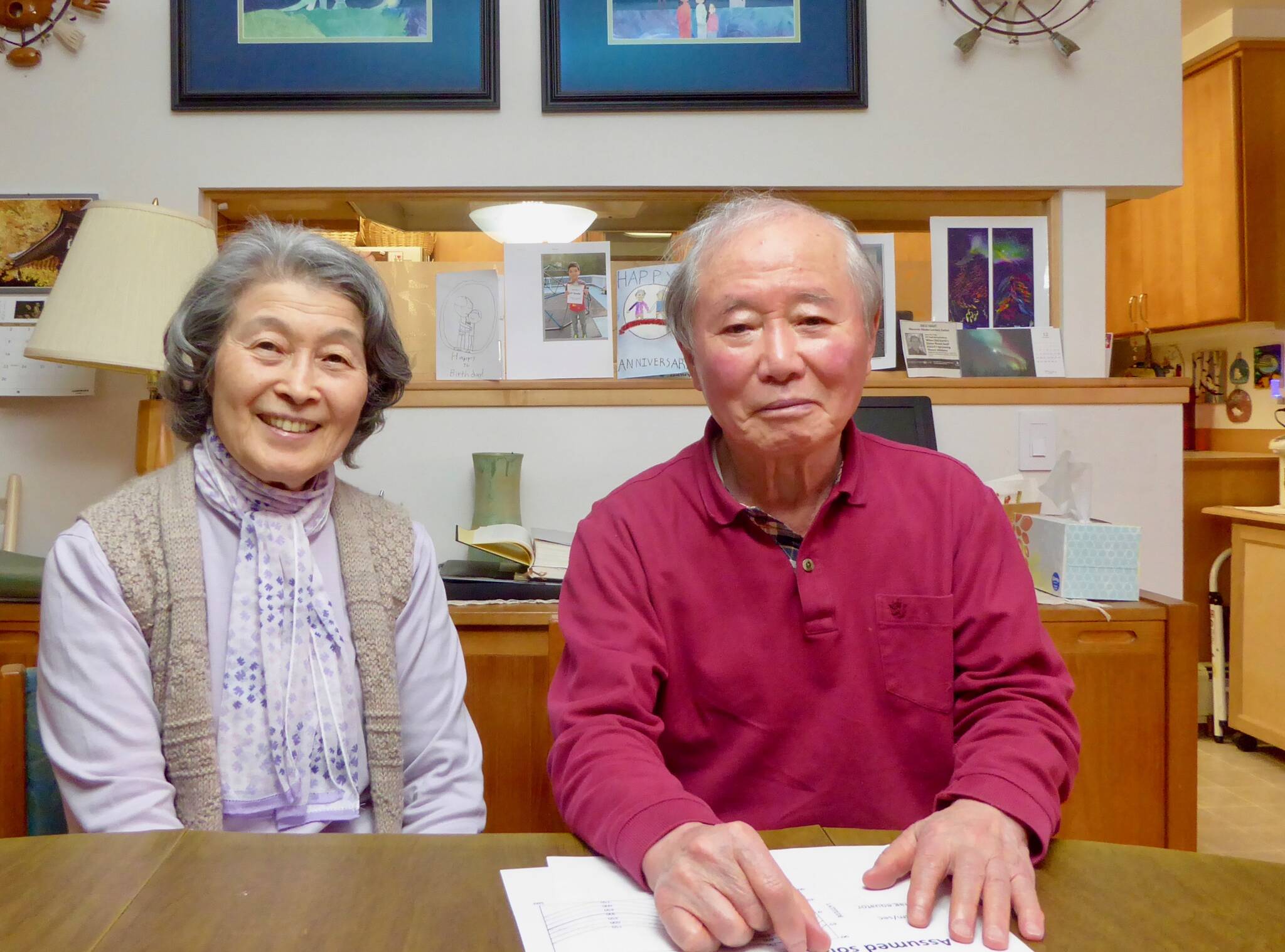

When Syun-Ichi Akasofu walks by in the building on the University of Alaska Fairbanks campus that bears his name, I want to catch up and give him a hug.

Why? For one, I really like him. For another, the longtime expert on the aurora is responsible for this hilltop structure in which I have written from a pleasant office for most of my career.

This week, the 92-year-old Akasofu is receiving an honor for an achievement that’s not as obvious as the sun-catching building that houses the International Arctic Research Center he brought to life a quarter century ago.

Explore Fairbanks — a local tourism booster — is inducting Akasofu into its tourism hall of fame. Leaders there cited Akasofu’s work in developing the local aurora tourism market, especially among Japanese people.

Curious about the aurora and ready for adventure, Akasofu came to Fairbanks from Japan 64 years ago when he was 28 years old. Since then, he authored probably the most famous paper ever written on the aurora, became an expert on the northern lights and was the leader of the Geophysical Institute.

When that place was running out of room in the 1990s, he raised millions from sources as diverse as the Japanese government and the city

of North Pole. With them, he helped create a grand building that became home to scientists studying climate change.

The International Arctic Research Center became an entity on its own. Akasofu was its first director. During those years of fund raising, people-managing and writing scientific papers, he also helped enhance a budding Alaska industry.

Many Japanese people are fascinated by the aurora because it is rarely visible there and people think it is a sign of good luck, said Tohru Saito of the International Arctic Research Center, a colleague of Akasofu’s.

“Lots of them say, ‘Before I die, I’d like to be able to see it,’” Saito said.

When he was director of the institute that housed several space physicists like himself, Akasofu worked with Japan Airlines to charter aircraft from Tokyo to Alaska. The planes filled with people who wanted to see the aurora.

“He would meet those tourists and welcome them and talk to them so that they could understand what it was they were seeing,” said Ron Inouye, a friend of Akasofu’s and a UAF Rasmuson Library retiree.

Inouye also credits Akasofu with helping others to learn about Frank Yasuda, who worked aboard the U.S. Revenue Cutter Service’s Bear at the turn of the last century. Yasuda and a group of Inupiat left Utqiaġvik and walked to the Yukon River to establish the community of Beaver. Novelist Jiro Nitta wrote “An Alaskan Tale,” a popular book in Japan, about Yasuda. Akasofu was responsible for getting that book translated into English.

“Japanese tourists have a fascination with Yasuda and still venture (to Beaver),” Inouye said.

From the time Akasofu heard a siren on the UAF campus that signaled Alaska had just become the 49th state and through his long career, Akasofu became a living conduit between Japan and his adopted home in Alaska. That probably helped in making this small U.S. city in the sub-Arctic a destination for Japanese tourists.

“People in Japan are also proud of (a Japanese person) making it big,” Saito said. “In that sense, he helped put Fairbanks on the map.”

• Since the late 1970s, the University of Alaska Fairbanks’ Geophysical Institute has provided this column free in cooperation with the UAF research community. Ned Rozell is a science writer for the Geophysical Institute.