Lonely northern cliffs from which scientists have pulled the bones of Alaska dinosaurs also hold the fossilized remains of birds.

Lauren Keller is studying the tiny specks of teeth and bones of birds that died more than 70 million years ago in what is now northern Alaska.

Keller is a graduate student working with the University of Alaska Museum of the North’s Patrick Druckenmiller, one of the researchers who has helped recover the bones of hadrosaurs and other dinosaurs from bluffs of the Colville River in northern Alaska.

About 73 million years ago, those rocky hillsides rose with the Brooks Range from the flats that now include the largest river that drains waters from Alaska’s North Slope into the Arctic Ocean. The rocks there and in some nearby “microsites” hold evidence of the world’s farthest-north dinosaurs, including 25-foot plant-eating hadrosaurs and tyrannosaurs that ate meat.

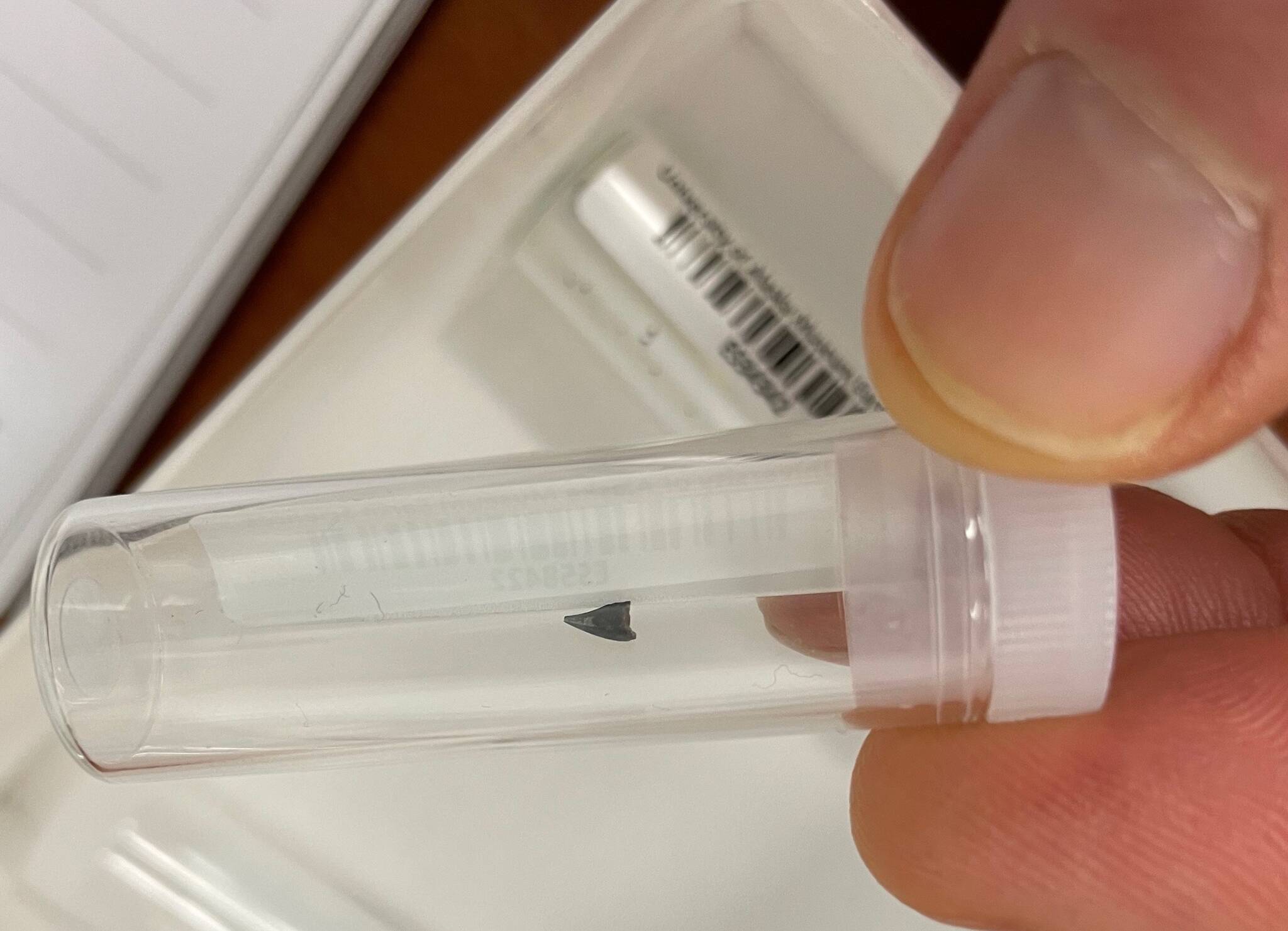

As another researcher once looked through sifted material from one of the sites, he noted flat, triangular little arrowheads that he guessed might be shark teeth. Druckenmiller, an expert on prehistoric marine creatures, thought they looked more like bird teeth. A closer look at remains from the Colville bluffs revealed more teeth — and fragments of bird bones.

Keller is now on the job of finding out more about these prehistoric birds as she earns a master’s degree. She traveled last spring (a time up there most people would call winter, with subzero temperatures and snow as far as she could see) to the Colville River to dig for clues about what the area was like in the time of the dinosaurs.

Back then, the land was even farther from the equator than it is today. Keller

described the environment there 70 million years ago during a recent presentation on the University of Alaska Fairbanks campus.

“The animals there were dealing with 120 days of winter darkness, and snow,” she said. No evidence of prehistoric amphibians, crocodiles, turtles or lizards at the sites, she noted.

Despite being so far north, the climate there was warmer than where Keller lives today in Fairbanks. The prehistoric North Slope supported a coniferous forest and many ferns. It was perhaps similar to what people in Juneau experience today, though much darker in winter.

Scientists have found at least 14 species of dinosaurs lived there, as well as six types of mammals, some fish and at least two kinds of birds.

The prehistoric birds Keller is piecing together were not like today’s birds, she said. For one thing, birds today have no teeth.

“Birds are dinosaurs,” she said. “There are real links between them.”

One such connection is the wishbone you find in your Thanksgiving turkey that T. rex also sported in its chest. Birds and the largest dinosaurs also had bones filled with air (which, being lighter than solid bones, helps birds fly).

Some of the bones have abundant grooves and pits, evidence of a young bird that was growing fast. Keller’s colleagues have found these flecks of evidence in the museum’s lab while picking apart soil samples carried back from the Colville River.

Keller has questions about these extinct birds that more studies might help answer. Such as: Did the birds migrate away from northern Alaska in the fall as so many species do today?

She noted that about 200 species of birds make their nests in the Arctic now, taking advantage of vast wetlands and the greenery and insects they nourish. At the end of her talk, she contemplated the tiny bird bones in her palm and what they mean.

“For 73 million years, birds have nested in the Arctic,” she said.

• Since the late 1970s, the University of Alaska Fairbanks’ Geophysical Institute has provided this column free in cooperation with the UAF research community. Ned Rozell ned.rozell@alaska.edu is a science writer for the Geophysical Institute.