By Ned Rozell

On a December night more than 60 years ago, a 28-year-old Japanese student touched down in Fairbanks, Alaska. He set down his suitcase as he stepped off the plane and looked northward, hoping to see the aurora borealis.

On Dec. 4, 2020, Syun-Ichi Akasofu will celebrate his 90th year on the planet. Akasofu has lived in Fairbanks ever since that frigid evening of his arrival, back when Alaska was not even a state.

Here, he became an authority on the aurora, and after that the director of the Geophysical Institute at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. He later used his reputation and connections to establish the International Arctic Research Center. His look-away-from-the-crowd nature once made a writer describe him as Alaska’s climate change skeptic.

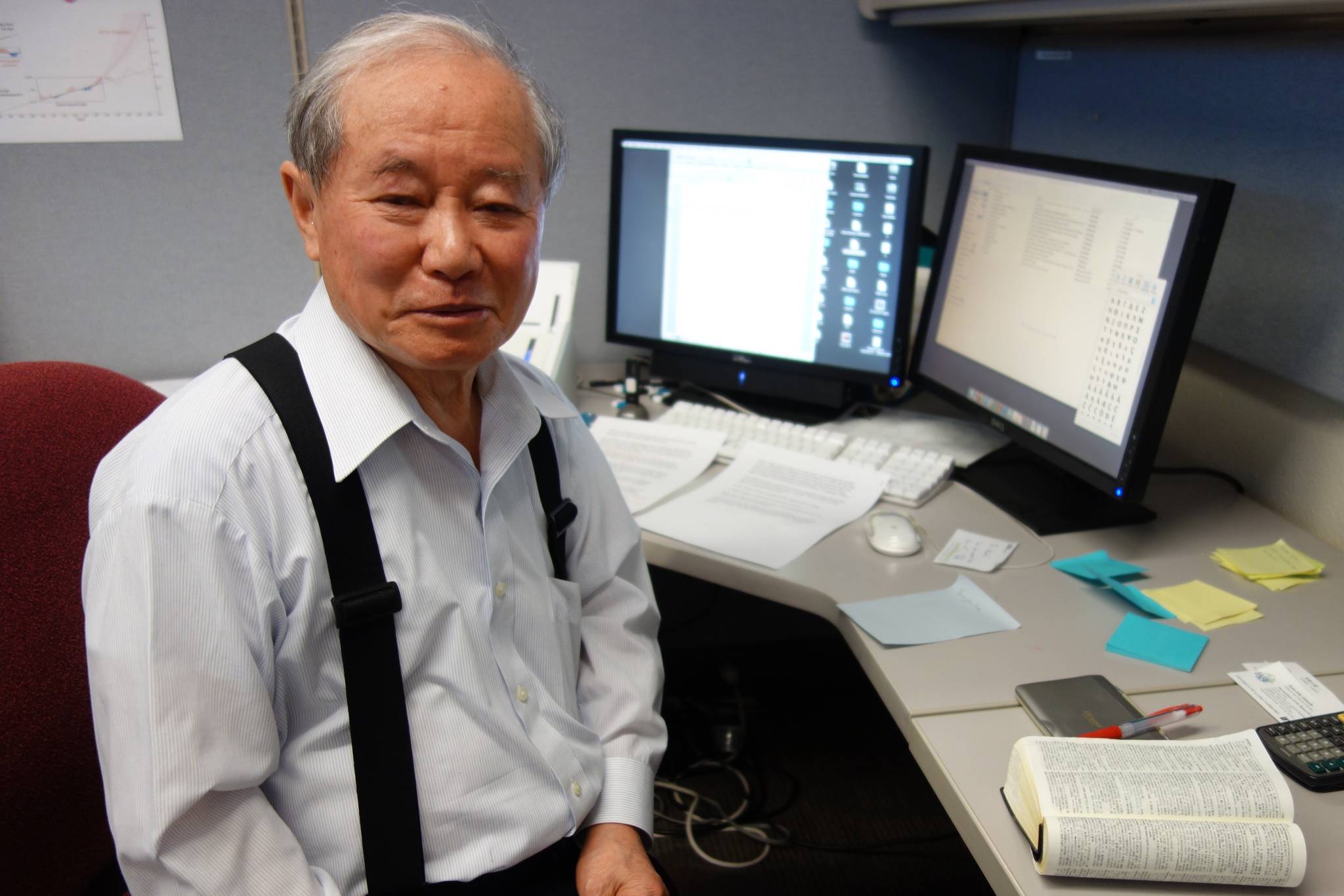

Wearing suspenders and a button-up dress shirt, Akasofu would — every weekday until the 2020 pandemic — drive 3 miles into the university for a few hours. His work space is a cubicle in the Akasofu Building. That sun-catching, metal-and-glass structure on the highest part of the Fairbanks campus houses a science institute — the International Arctic Research Center — that would not exist without him.

Akasofu’s Alaska journey began when he wrote a letter to Sydney Chapman, a British space physicist who lived a reverse-snowbird existence, living in Fairbanks in the winter and Boulder, Colorado, in the summer.

University of Alaska officials had persuaded Chapman, an authority on the electrical activity in the thin air a few hundred miles above our heads, to come to Alaska. He said yes, but only if he didn’t have to be an administrator and could work on his studies.

Akasofu was interested in the aurora and was having trouble understanding a space-physics paper Chapman had written.

Chapman replied to Akasofu’s letter. He answered a few Akasofu’s questions and asked if the young man might want to answer some himself, in Alaska. Chapman included a check for $500. Akasofu spent the money on a ticket to Alaska.

That $500 gamble paid off for Chapman, who was looking for graduate students to populate the Geophysical Institute.

Akasofu looked at films of aurora from stations all over the top of the globe. He saw how the aurora was an oval, rather than a perfect-circle halo around Earth’s poles, which was the theory at the time. He later noticed nightly patterns of auroral explosions, which he called “substorms.” Akasofu’s 1964 paper on substorms, co-authored with Chapman, became a classic scientists still cite today.

Despite him establishing a paradigm, Akasofu said he is not a fan of scientific theories set in concrete. He once challenged students and researchers to trust their instincts.

“When you find something that doesn’t fit, don’t throw it away,” he said in 1998. “You may be wrong, but if you’re convinced you’re right, pursue it. You might be the one who establishes the next theory or paradigm.”

A career contrarian, Akasofu after retirement studied the history of global temperatures. He pointed out that if one looked at climate records from long enough ago, a person could argue we are living in a warm period between ice ages. His contemporaries were not all thrilled with this theory, especially after Rush Limbaugh and others cited Akasofu’s arguments.

Their reactions reminded him of earlier in his career, when reviewers rejected ideas in his space-physics papers using the words “naive,” “rebellious” and “mystical.” He kept a list of those words in his office.

Akasofu has come a long way from the Nagano, Japan, where one of his first memories is his mother singing him a song about Siberia. The 5-year-old boy could understand most of the lyrics, except for “aurora borealis.” She told him it was “something beautiful in the sky.”

His interest in the aurora, beneath which Akasofu has lived most of his life, led him from research to management. He became the director of both the Geophysical Institute and later the International Arctic Research Center.

The latter was first planned as an expansion of the Geophysical Institute but evolved into its own research entity. Akasofu raised millions to make construction possible, finding contributors in Japan and anywhere he could.

I remember a photo from the groundbreaking for the International Arctic Research Center. Akasofu was standing there in a hard hat, in a line with other university bigwigs. Very serious. But on closer look, he was holding up two fingers behind the hard hat of the man next to him.

He laughs a lot. I’ve wondered how much that endearing trait contributed to this boyish Japanese guy rising to such a high rank in America.

He was the director of the Geophysical Institute when I first hiked along the path of the trans-Alaska pipeline in 1997 and wrote columns along the way. He said he wanted to come along with me for a bit of walking, but he was a busy guy.

One warm summer morning, as a friend and I camped on the north bank of the Yukon River, we heard the whop-whop-whop of a helicopter. It landed nearby, and out of a cloud of dust stepped Akasofu, along with the president of Alyeska Pipeline Service Co. We chatted for a bit, then he passed us a bag of cookies his wife, Emiko, had baked.

A month later, on the wintry day I completed that 800-mile walk, Akasofu showed up at Prudhoe Bay. In Pump Station One, where Alyeska officials let me stay for the night, Akasofu walked in wearing hiking boots and wool socks. He shook my hand, said good job, and handed my dog, Jane, a rawhide bone the size of a mammoth femur.

• Since the late 1970s, the University of Alaska Fairbanks’ Geophysical Institute has provided this column free in cooperation with the UAF research community. Ned Rozell ned.rozell@alaska.edu is a science writer for the Geophysical Institute.