In video after video, young giggling teens can be seen filming themselves and each other playing the “passout” or “choking” game.

“That is how you make … people pass out,” says a teen boy in one clip after demonstrating the move on his girlfriend. “It’s really funny.”

A quick internet search uncovers one YouTube channel devoted just to these choking game videos, with 154 listed; each one has thousands of views.

But the “choking game” — which is also known as flatliner, space monkey, blackout, the knockout challenge and the fainting game — can have deadly consequences.

Just six weeks ago, an Auke Bay boy was found not breathing in his room after possibly playing the game by himself. Eleven-year-old Kolbjorn Arndt never regained consciousness and died April 27.

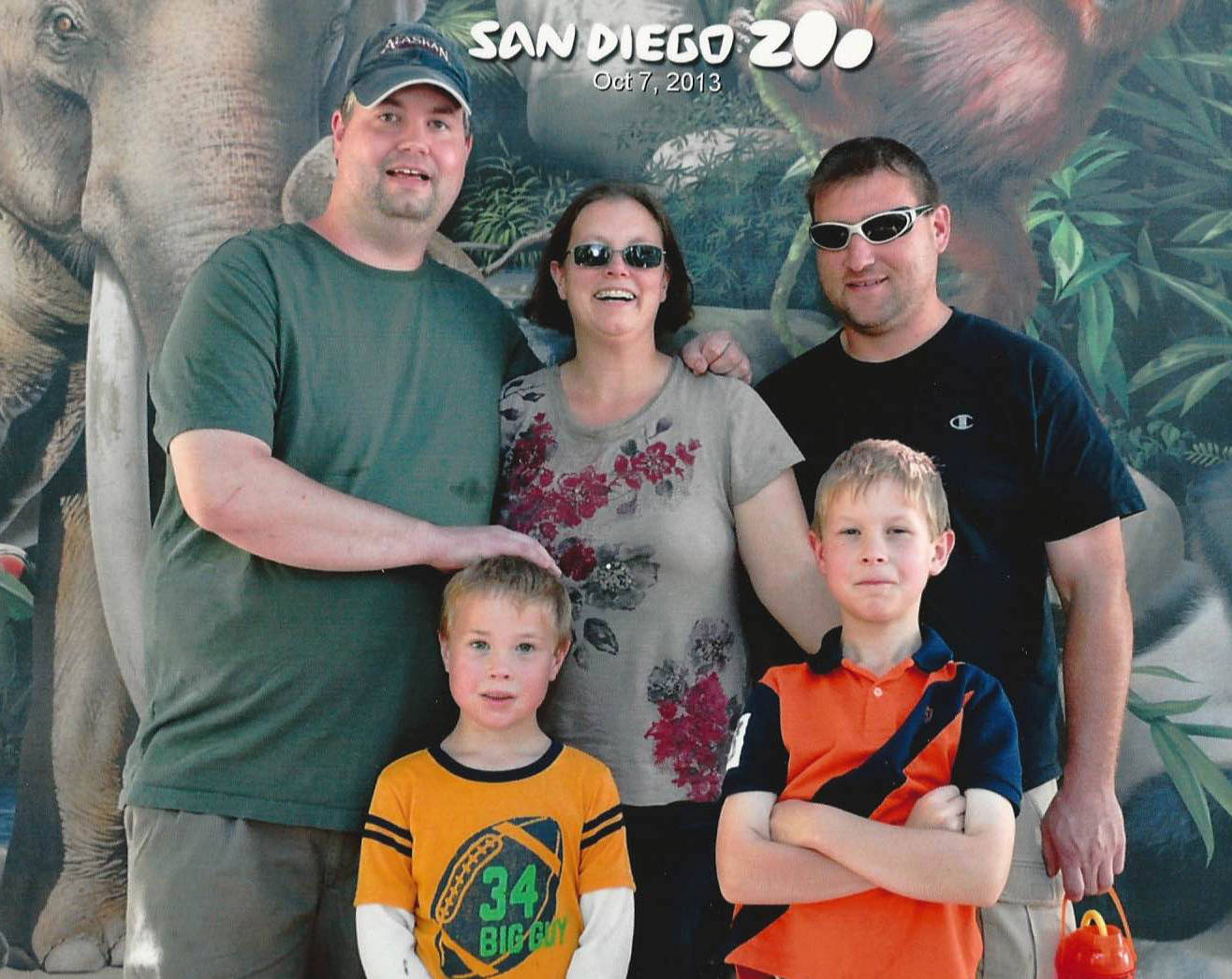

Kol’s parents, Travis and Karragh Arndt, said that before his death, they had never heard of the choking game.

“You worry about a million things, but that was not on the list,” said Karragh. “It was unimaginable.”

The Arndts agreed to speak publicly about Kol’s death in the hopes of preventing a similar tragedy from striking another family.

“The important thing is that no other kid does this, that parents realize these videos are out there,” Karragh said. “The consequences shouldn’t be so huge. … It’s really not fair. For an 11-year-old — he couldn’t understand the consequences. It didn’t occur to him.”

These pass-out activities involve children, either alone or with others, strangling themselves with the intent of getting a rush of euphoria as they regain consciousness. While the choking game has been around for decades, it appears to have become common again. In May, a choking game death in New Jersey drew national attention.

It’s difficult to find accurate statistics about the number of children and teens who die as a result of the dangerous game because deaths by asphyxiation can be attributed to suicide. According to GASP (Games Adolescents Shouldn’t Play), an international organization dedicated to putting an end to the choking game, there were eight reported victims in 2016 ranging in age from 11 to 16; only two of those survived.

11-year-old was always on the go

Kol Arndt lived his life at “110 percent at 110 miles per hour,” his parents said, adding that even as an infant, Kol ran in his sleep, waking himself up. Travis recalled an incident when Kol — about 6 at the time — got out on the roof of the house while his brother Kallum, two years younger, and a friend tried to help him down.

“Luckily, they couldn’t carry the ladder,” Karragh said.

On another occasion, the boys decided to create an escape hatch from a bedroom — by sawing a hole through the sheetrock.

“They were so cute,” Karragh said. “It was hard to be frustrated with them.”

Kol preferred to be outside and to be active, his parents said. The Auke Bay Elementary School student was a Boy Scout and participated in wrestling, baseball and football, as well as loving to fish and ski.

That Monday afternoon, the last day of wrestling practice, Kol had been up in his room for about 15 minutes, she said. Kallum and a friend were the ones who found him.

“They came down and told us he wasn’t breathing,” Karragh recalls. “The words just didn’t register.”

Karragh and the other boy’s mother “flew” up the stairs and the neighbor performed CPR until Capital City Fire/Rescue responded and took over.

“It was so helpful the neighbors knew CPR,” Travis said. “Without that, there would have been no chance. You never know when that could be really useful. If you know even a little bit of CPR, it’s better than nothing. It’s still way better … to give someone a chance.”

Kol was taken to Bartlett Regional Hospital, where he was stabilized; he was flown to Harborview Medical Center in Seattle that night.

“We had hope, in the beginning,” Karragh said.

“We were optimistic, it seemed like things were improving — he was breathing on his own,” Travis said.

But Kol’s brain began to swell and he died that Thursday without ever regaining consciousness.

Travis said he had never previously given much thought to organ donation, but they found it a “huge gift” to be able to donate so many organs — including Kol’s lungs, liver, kidneys and corneas — to give others a new chance at life.

A deadly game

“We were trying to figure out what had happened and why,” Travis said. “He wasn’t depressed. … But that was what we had — until we heard about (the game) from the school.”

The Arndts stress they are not completely sure what happened, but that some of Kol’s friends told teachers at the school they had been talking about a choking game video they saw on the internet, where it made it seem like a game, that you couldn’t get hurt.

“It made it seem safer than it was,” Karragh said, “that you can’t get hurt if you do it this way. … Someone called it the choking game, but we’re not sure they called it that. I think they referred to it as a trick or a prank.”

Neither parent believes that what happened was intentional or that Kol even understood that choking causes euphoria.

“He was into practical joke videos, pretty innocent little 11-year-old jokes,” Karragh said, speculating that a choking game video popped up while he was channel-surfing those types of clips.

“He did before he thought,” she said. “I’m sure he thought it would be a great idea, to learn this (passout) trick.”

Both Travis and Karragh wanted to stress to other parents how quickly a child can get themselves into trouble, with Karragh pointing out that it only takes 15 seconds to start to lose the ability to make a rational choice.

In Kol’s case, he was taller than the bunk bed, so clearly he had been leaning back and passed out with his weight holding him in that position, Travis said. If he had been able to stand up, that would have relieved the pressure.

“A 30-second mistake costs you everything,” he said. “This was too high a price to pay.”

“I would give anything if I could go back in time for five minutes,” Karragh said.

Unlike depression, there were no warning signs to clue the Arndts in to impeding tragedy.

”It just came out of the blue,” Travis said. “It could be anybody, how seemingly random it was. I just hope it doesn’t happen to other people. That’s the hard thing. You can’t stop (these) videos from propagating. It’s probably becoming more prevalent — how do you get a handle on it?”

Education is key, experts say, whether it is in school through risk prevention curricula, or at home through frank discussions. Parents are urged to talk with their children about these activities; they can also check the search history on their children’s phones, tablets and computers.

Celebration of Kol’s life set for Saturday

On Thursday, the Arndts were preparing for Kol’s memorial service, set for 1 p.m. Saturday at Thunder Mountain High School.

“There will be a kid-oriented service at 1 p.m. followed by a potluck lunch in the commons,” read the announcement. “As Kol loved to play with his friends and was always doing something active, we have reserved the gym until 5 p.m. so that the kids can play and hang out together. Dress is casual and we encourage people to wear clothing from activities they might have participated in with Kol like school shirts, field day tie-dyes, jerseys, or uniforms.”

The couple said it only made sense to make sure Kol’s memorial service was kid-centered because he had so many friends across Juneau from the many sports activities he was involved in. The play component was especially important, Karragh said, so that his friends would have a time to do the things that he would have loved.

Travis said their front yard had always been a place for the neighborhood kids to congregate, adding that it has been very quiet out there since Kol died.

“I don’t know if it will ever be OK, not having him here with us,” Karragh said. “Kol was a great kid with a big imagination. There wasn’t a day where he didn’t make me laugh with his antics and his adventures. I don’t know what we are going to do without him.”

For more information, go online at www.erikscause.org or jacob’s-challenge.org.

• Contact reporter Liz Kellar at 523-2246 or liz.kellar@juneauempire.com.