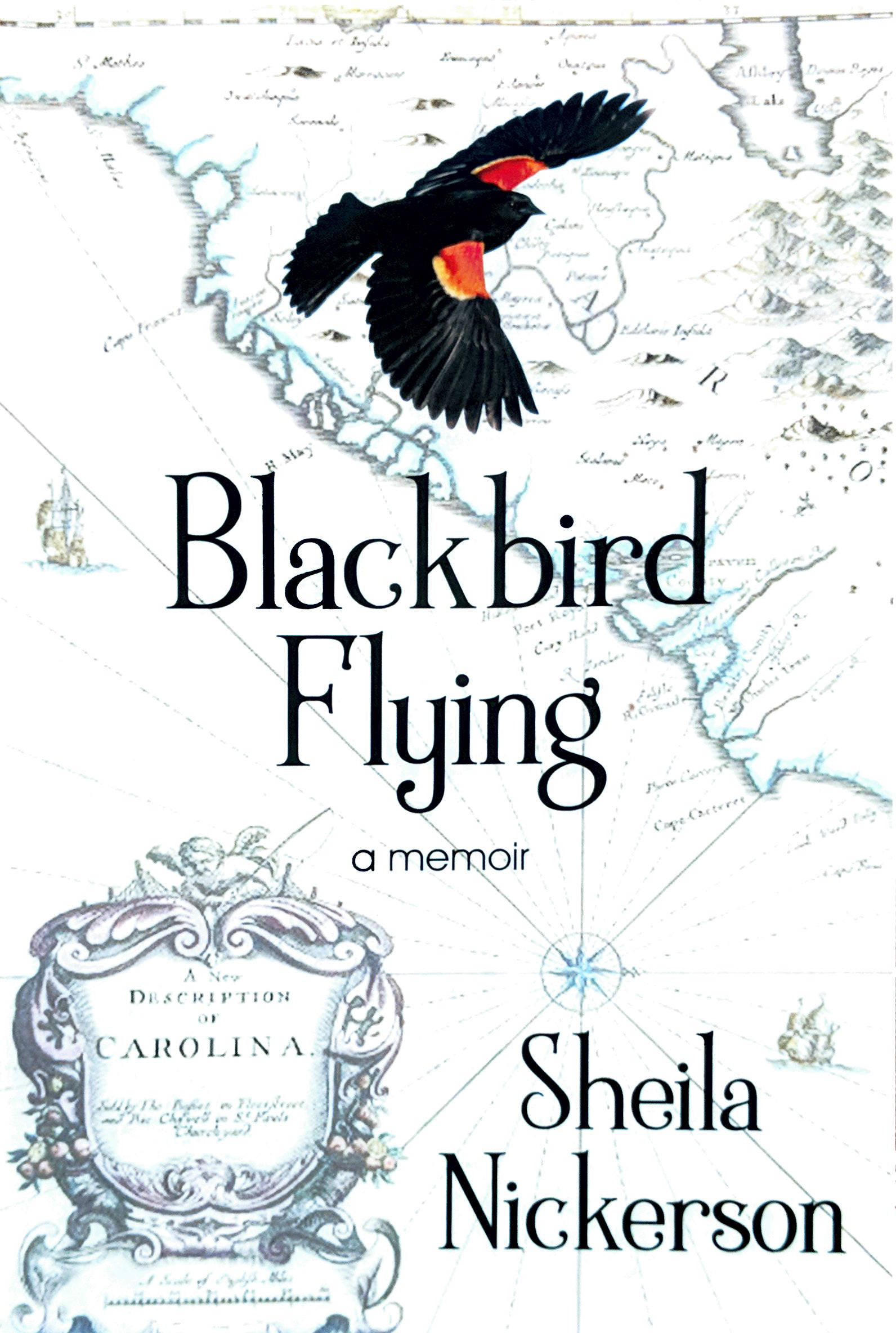

After Sheila Nickerson’s mother passed away, the former Alaska Poet Laureate and Juneauite realized she was now the oldest member of a family with a history of dementia.

Previously, there had always been an older relative to make decisions or pass along family stories. Nickerson said in a phone interview the idea that she was the one filling that role helped inspire her recent memoir “Blackbird Flying a Memoir.”

“Suddenly, I was that person, and that propelled me to do something about it, and that was to write,” Nickerson said.

The resulting book is an information-dense collection of personal stories shared through a didactic prism of shared knowledge about birds, colonial history and new physics. Sometimes it reads like Melville’s passages on whales, while other sections are thoughtful meditations on loved ones lost to alienation or death.

What We Are Searching for

When you look for birds, you are not alone. Even when you see no motion and hear no sound, you know they are nearby. Sometimes you can “Pish” and call them up. Sometimes you must simply be patient. However hidden, they are there. Like the object in the block of stone which the sculptor releases, they are there.

I think what we want most of all is not to be alone.

Usually, when we go in search of birds, we go in groups. There are many reasons —safety, the need for educational leadership, shared resources and information, possibilities for instant verification, corroboration, and, simply, companionship. We do not want to be by ourselves when we discover something of wonder. If we are alone, we immediately think of all those with whom we would like to share the experience. We hurry out of the woods-jungle-desert to proclaim our find. We seek our flock and tell our story. Storytelling is what connects us and keeps us part of the tribe. Storytelling is what reinforces memory and defines our species. It validates our legacy and clarifies our itinerary. It serves as a signpost on the way. Searching, discover, sharing: This is our work.

Even when there are no blackbirds and the lawn looks vacant and lonely, the air is not. The air is the great invisible continent, the country of everything, and everywhere we stand is its shore. Chief Seattle, of my northwestern home, is said to have stated that every place is filled with memories and spirits: “In all the earth there is no place dedicated to solitude.”

Birdwatchers come to the edge. But they know too that eventually they must follow their subject inside—whatever lies beyond the boundary. Sailors have a different way of putting it: Eventually, they say, you have to leave the harbor.

I wanted to follow blackbird, my species, into new areas where we could find a living and thrive. For too long we had been splitting up and weakening, losing property, losing influence, losing stature and recognition. I did not know my cousins and could barely say their names. I wanted my flock to flourish, and I wanted to flourish with them. It was time to push forward, crossing borders, but to where?

— Excerpt from “Blackbird Flying: A Memoir”

Nickerson, 77, of Bellingham, Washington, took some time over the weekend to talk to the Capital City Weekly about how “Blackbird Flying” settled into its unusual form, the Beatles and her curiosity about what comes after this lifetime.

How are you doing? You are just a font of information on disparate topics from what I was reading?

There are a lot bits and pieces in there, I know that. I’m interested in so many different subjects and different areas that I just have to explore them to a certain extent.

Have you always been that way? A life-long learner type? If so, what sources do you gravitate toward because it seems like there’s a lost art of research in the digital age?

I’ve always wanted to explore as much as I can sitting in an armchair. I don’t want to be the one out in the Arctic wilds, but I want to know what goes on there. I couldn’t agree with you more about the fading of science and scientific fact. We seem to rely more and more on what is digital and that can certainly lead us astray.

Having lived on pretty different parts of the country — including New York, Alaska, Washington, South Carolina — how do you think wildlife colors our perception of place?

I think it makes it more interesting. It makes you want to go there and see it for yourself.

Have you kept up with Alaska current events? Do you have any thoughts on the state of the state?

I think it’s very sad. I think the push toward privatization and all that is happening in terms of the budget and politics is very disturbing and very very tragic. The threat to the arctic wildlife for instance is very, very disturbing to me.

[Art work says, “Gut fish, not Alaska”]

How did you come to decide to share personal stories and realizations through the prism of bird and explorer information?

I just wanted to pursue what I found to be very interesting, and John Lawson was particularly interesting to me because he was so organized and so ready to take on not only the wilderness and everything in it, but also the political and social situations he had to cope with.

I let it take its own shape. It’s what I’ve always done with poetry, which is what I’ve concentrated on most in my life. I’ve just always let the poem or whatever it is form itself.

This is more of a goofy question, but I couldn’t help but notice one of the chapter titles is a “Blackbird” reference? Are you a Beatles fan? Favorite album? I don’t know when I’ll ever get another chance to ask.

I am a Beatles fan, but I couldn’t give you the name of a single piece, but I certainly have always been a Beatles fan.

Your book often alludes to a broader mystery beyond our perceptible world as well as an afterlife. Is that exciting or daunting to you?

I’m beginning to find it exciting as I get closer to it. I’m beginning to think it’s very interesting and necessary to move on to that next dimension to explore it and to experience it. I feel much less afraid and much more confident that there’s something very real and very exciting to go to.

Did you grow up in a faith?

Roman Catholic, since I come from an Irish family. I am obviously pretty involved or was involved in the Roman Catholic faith, which I abandoned in my early 30s. When I was in Juneau, as a matter of fact. It was during mass at the Catholic church there, and the old priest started talking about the role of women and the responsibilities of women, and something just clicked. It was just a reaction. I just said, ‘This is ridiculous.’ I don’t think I got up and left in the moment, but I virtually never went back to church.

So what informs that sense of something else, next step?

There has to be something to go on to. There couldn’t be all this design and activity and all of these forms of life simply to be on one planet at one time. It just seems more and more to me there has to be something beyond, and I’m quite convinced there is.

[Colorful crosswalk comes to Juneau —legally this time]

• Contact reporter Ben Hohenstatt at (907)523-2243 or bhohenstatt@juneauempire.com. Follow him on Twitter at @BenHohenstatt.