In his recent book “Black History in the Last Frontier,” University of Alaska Anchorage history professor Ian Hartman sheds light on the contributions Black people have made in Alaska before and after statehood.

“They hunted for whales, patrolled the seas, built roads, served in the military, opened businesses, fought injustice, won political office and forged communities,” Hartman wrote in his introduction. “This book presents their stories and documents a seemingly improbable topic: the history of black settlement and life in Alaska.”

The book began as a project for the centennial celebration of Anchorage in 2015, Hartman said in an interview with the Empire, and is a collaboration between UAA and the National Park Service. But given the wealth of information available, what was meant to be a single chapter grew into a full-length book.

According to Hartman, the Park Service project was to be fairly modest in scope. But the amount of information contained in the George T. Harper papers at the UAA/Alaska Pacific University Consortium Library gave the author a lot to work with.

“The biggest thing was just the extent to which African Americans have played a role (in Alaska’s history),” Hartman said. “Going back to whaling. Whaling crews tended to be some of the most diverse, certainly you find evidence of Black whalers before the Civil War, of Black involvement before the days of the (Alaska) purchase.”

Originally published in 2020 by the University of Washington Press, Hartman said the book is available for free from the NPS website.

“Black whalers were among the first Americans to reach Alaska, specifically its southeast panhandle in the early 1840s,” Hartman wrote. “These men were also among the first to view the icy waters of the Arctic by the late 1840s and early 1850s.”

[Gara announces running mate in gubernatorial race]

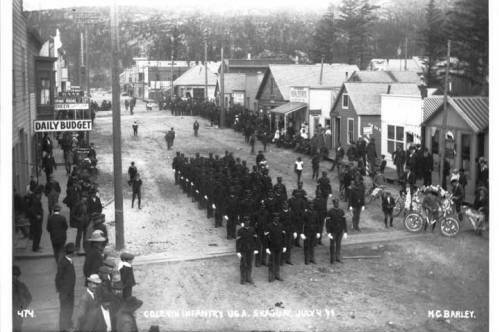

There are several well-known instances of Black contributions to Alaska’s history, Hartman said, such as the engineers that worked on what would become the Alaska-Canada Highway and the Black calvary soldiers known as “Buffalo Soldiers” deployed to the territory in the early days of the Yukon Gold Rush.

Hartman gave the example of Thomas Bevers who settled in Anchorage in the early 1920s. Bevers was Anchorage’s first paid fireman in 1922 and established a fur trading company that helped establish the industry in the city. Bevers was mixed-race, and according to Hartman could pass as white, which he sometimes did to avoid racial animosity.

“Bevers, along with others in the young community, initiated an annual fur-trading exposition, an event Alaskans recognize today as Fur Rendezvous,” Hartman wrote.

According to Hartman, many Black people would come to Alaska but few would stay. Many came in waves to work on various projects like the Alcan Highway and the railroads, but most came as part of the U.S. military.

“A lot of this (migration) is through the military,” Hartman said. “It becomes impossible to ignore the military.”

Following World War II, more African Americans would end up staying in Alaska, Hartman said, and the oil boom of the 1970s would bring more workers who ended up staying.

Later figures covered in Hartman’s history include Mahala Ashley Dickerson, Alaska’s first Black homesteader and lawyer. Dickerson, who died in 2007, filed a claim for a 160-acre homestead near Wasilla in 1958 and a few months later would pass the Alaska State Bar examination, becoming the state’s first Black lawyer. This was after Dickerson became the first Black woman lawyer in Alabama in 1948, and the second Black woman lawyer in Indiana after she moved to that state in 1951.

Dickerson published a memoir in 1998, “Delayed Justice for Sale.”

Hartman said as he began the project in 2015 the Black Lives Matter movement was just starting to coalesce and there was increased interest in issues of race and Black history. There are several people interviewed for the book who are still alive, Hartman said, and whose willingness to be interviewed was integral to the project.

“I couldn’t have done this project without their knowledge,” Hartman said. “I would really emphasize the people who really hold this knowledge are in the community.”

Contemporary sources interviewed by Hartman include community activist Cal Williams, former President of the Anchorage NAACP Ed Wesley and civil servant Elinor Andrews.

“I think what I’m most proud of is that it includes people who have very much shaped Alaska’s history in the current,” Hartman said. “(The book) highlights the people who have made deep contributions to the state that people might not be aware of. Many of these people are still active in the community, there’s a lot we can learn from them.”

• Contact reporter Peter Segall at psegall@juneauempire.com. Follow him on Twitter at @SegallJnuEmpire.