This article has been corrected to note the Gastineau Channel Historical Society, not the city, currently operates the Last Chance Mining Museum.

It was the middle of the Great Depression in 1933 when Juneau received exciting news that would change the community forever.

President Roosevelt’s New Deal allotted funding to build a bridge connecting Douglas Island and Juneau. The Works Progress Administration (WPA) had been developed to put people to work when economic hard times shuttered many businesses.

Fortunately, Gastineau Channel’s mines continued to operate although there was a cloud of discontent over a pending strike. Douglas was in a slump after the collapse of underground Treadwell Mine tunnels years earlier. A flood had filled most of the underground workings with seawater when the channel flushed into the many tunnels beneath it on a tragic April day in 1917. No one was killed.

For many Americans the new WPA provided hope, jobs and opportunity.

The goal of a bridge was first envisioned in the early 1900s, but had been thwarted by the Treadwell Mine disaster and World War I. The 1920s brought a return to prosperity until the 1929 U.S. stock market crash. Meanwhile, mining operations on the Juneau side were ramping up.

Successful lobbying by Alaska Territorial Gov. John Troy, an appointee of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and others secured funding for a bridge from the federal government and design work began. To keep costs down the site chosen was the narrowest point between Douglas Island and mainland Juneau. An early plan to link up from Eleventh Street was abandoned and Tenth Street became the bridge connector.

Building the first channel bridge

Before Douglas could connect with Juneau, however, more than a mile of new road and a complicated bridge across Lawson Creek had to be built. Locals take for granted today these essential features that were momentous construction efforts in 1934 and 1935.

Some of the most challenging work was setting the concrete support piers in Gastineau Channel. Strong currents and tides made work hazardous and difficult. Juneau’s extreme tides can range from minus-four feet to plus-20 feet within six hours at certain times of the year.

Nasty winter weather delayed progress by two months when a strong storm hit Juneau on Nov. 10, 1934.

“The excavation of the last pier was nearly completed and several bearing piling had been driven,” a newspaper story relates. “A timber cribbing was being sunk to facilitate the work, instead of using the steel sheet piling as in the other large pier. The storm washed out the cribbing, partially filled in the excavation, and washed away both the steam rigging scow and the supply scow, beaching them up the channel on Douglas Island.”

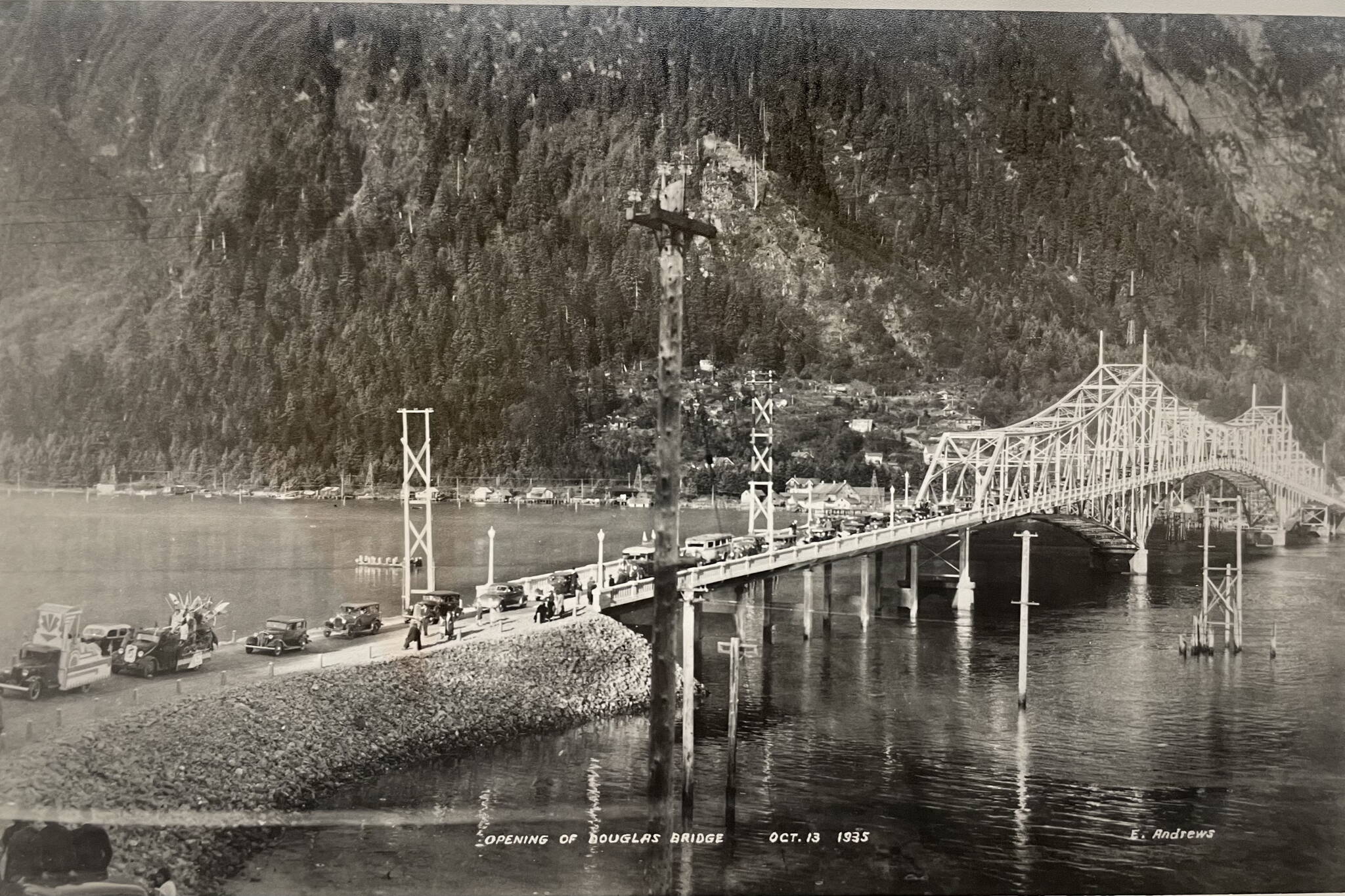

The cross-channel bridge construction project was incredibly efficient. From receiving the news of allocated funds in December 1933 to the grand dedication on Oct. 13, 1935, only 22 months had elapsed. In June of 1935 a news article celebrated the arrival of the final section of steel for the bridge. When it was hoisted into place the connection was only five-eighths of an inch off. Earlier a fleet of trucks had hauled waste rock from the Alaska Juneau Gold Mine’s rock dump to build the approaches under the guidance of R.J. Sommers.

In a special edition about the bridge, the Daily Alaska Empire on Oct. 13, 1935, described details of the bridge construction.

“Two large piers each rest on a 200-yard concrete base. Each base encases the heads of 75 bearing piling which penetrate to a depth of 50 feet below. Each large pier contains about 900 yards of concrete.” Coffer dams were built 25 feet below water. Concrete was poured in one continuous pour. Then the coffer dam was dewatered and the remaining 240 yards were poured in the dry air, the report says.

A celebration marks completion

Despite these setbacks, the bridge was dedicated with a grand parade on sunny Oct. 13, 1935. The night before there had been formal dress balls to celebrate. Midday on the 13th, an honor guard from the U.S. Coast Guard cutter Tallapoosa led the procession from Juneau. Gov. John Troy rode in the lead vehicle. Festively decorated floats with Bridge Queens, and their courts from Douglas and Juneau, met in the center of the bridge. Juneau Queen Birdie Jensen and her court of young women greeted Douglas Bridge Queen Phyllis Edwards and her entourage in the center.

Douglas Mayor A. E. Goetz shook hands with Juneau Mayor Izzy Goldstein across the white crepe paper ribbon delineating the separation being bridged. The ribbon was cut by the young daughter of the Douglas mayor while Mrs. Robert Bender christened the bridge by smashing a bottle of champagne on the steel structure. There was music and speeches of praise then a flood of automobiles drove from one side of the bridge to the other. Juneau photographer Trevor Davis filmed a movie that is in the collection of the Alaska Historical Library in the state museum downtown.

Key people in the construction effort were listed in the Empire’s special edition. Ike P. Taylor was the chief engineer for the Alaska Road Commission. O.H. Stratton designed the bridge. A.F. Ghigilone supervised the construction. The concrete piers were built by Alfred Dishaw of Juneau. The steel span was fabricated and erected by Pacific Car and Foundry of Seattle. A.W. Quist laid the decking. Concrete approaches were constructed by Warrack Construction of Seattle. The most expensive element was the steel span and floor for $118,963.27.

Engineer Stratton said of his design, it “has been, not only to give the best bridge for the money available, but to design a bridge that would fit in and become a part of the surrounding beautiful scenery.”

Time for a replacement

For 47 years that steel structure perfectly fit between the two towns with curving arches that replicated the sweep of mountains. However, after many years the bridge had exceeded its useful service life and plans were made to replace it. The original bridge was narrow and passing traffic was tight as vehicles passed each other with the occasional loss of a sideview mirror to brief collisions.

As the first bridge displaced the fleet of little ferries that motored across the channel, a new 1981 bridge made obsolete the 1935 steel bridge. Gone were the superstructure and the perfect junction in the center. The new concrete bridge sections met off-center. A dramatic day’s work is documented in the July 24, 1981, edition of the Juneau Empire as four cables operated as one well-choreographed unit to slowly raise the center section from a barge below held steady by two tug boats. Once the center was in place each protruding side structure settled downward 15-17 inches when they accepted the weight of the center section.

Juneau celebrated the installation of the second bridge more modestly than the first. The commemorative anniversary date of Oct. 13 was chosen to dedicate the 1981 structure. “The new bridge is a free-cantilever, segmental prestressed concrete box girder structure,” read the dedication brochure published by the Alaska Department of Transportation.

Dismantling the first bridge was similarly attention-grabbing when workers cut free the big center span of the old bridge and lowered it onto a barge. The Empire covered that moment in December 1981 with a front-page story.

So what became of the first steel bridge? While most of the 1935 structure was sold for metal scrap in 1982, some key pieces remain in Juneau today.

The 1935 bridge makes a home

Perhaps the most inventive use of bridge parts is the structural framework for a house. Bill Leighty and Nancy Waterman designed their house with advice from engineer Robert Lium, builders John Speas and Jim Laughlin, and architect Frank Maier. As a young couple, Nancy and Bill had operated the Gold Creek Salmon Bake along the creek near the historic A-J mine buildings at the end of Basin Road. Today the Gastineau Channel Historical Society operates the Last Chance Mining Museum in the former compressor building nearby in Last Chance Basin. To get customers to the salmon bake, Bill drove a refurbished yellow school bus from the cruise ship docks into the basin while Nancy and staff grilled salmon fillets over an alderwood fire on the bank of gurgling Gold Creek.

Bill and Nancy chose downtown Juneau to build a permanent new home. Searching the downtown hillside terrain from the Douglas Highway, they found two adjoining vacant lots that were for sale nestled between surface creeks on the flank of Mount Roberts. The site would be an ideal location for “an earth-sheltered” house. The year was 1982 and the worry of another capital move threatened the economy of Juneau and future of the region.

Hedging their bets, Bill and Nancy bought the land. When the capital was secured for Juneau, they proceeded. John Carstensen, project engineer for the company building the new bridge, sold them all the used structural steel for $5,000. Lots of concrete and rebar made the sturdy rear and side walls. A 21-inch-deep I-beam from the old bridge lay across the walls with four recycled bridge columns for vertical support. Nine box girders laterally supported the roof which was designed to survive a debris flow of 20 feet. The material would slide off the brow of the house and continue down the hillside, leaving the home intact.

Inside, a photographic mural of the bridge by famous early photographers Lloyd Winter and Percy Pond completely covers one wall of the living room. Taken from the Douglas side of Gastineau Channel, the photo looks up at the steel structure and concrete piers of the 1935 bridge.

Nancy and Bill are creative, resourceful and conservation-minded. The roof has a rooftop garden for vegetables and flowers. A wall of glass on the front of the house captures sun for a passive solar greenhouse.

Other uses for bridge parts

In addition to new life inside a downtown home, the bridge lives on in various forms around Juneau. Behind Jordan Creek Center two identical footbridges were built for pedestrians across Jordan Creek. Other bridges have been crafted on private property to span watery access to remote homes. Most of the steel, however, was sold for scrap and barged to Seattle.

Another creative use of bridge parts can be seen near the Mendenhall River in a boat storage yard owned by the Smith family. The Smith family’s construction business has played an active role in Juneau. Their dredge extracted fill material from a pond near today’s TEMSCO to create a portion of Egan Drive. Their family’s 1900 dairy eventually became the Nugget Mall property.

Joe Smith Jr. and his brother, Tim, worked with their dad, Joe Sr., starting in the 1970s. That work included helping remove the 1935 bridge when they were younger men. Recently Joe Jr. shared this recollection:

“I remember watching as large pieces of steel were cut free from the remaining structure after the center section had been removed. A lone worker would have to climb up to the beam and begin using a cutting torch to slice through the steel. The entire structure had many coats of lead paint which interfered with the torch flame causing slag spatter and releasing toxic fumes. I don’t remember respirators being used. When the beam was cut free and fell to the beach the remaining structure bucked and swayed. The worker was not in a basket or lashed up in any way, just hanging on for dear life.”

On a recent chilly October day, Joe Smith pointed out two significant remnants of the early bridge. Rusting on the ground are two large fittings Joe has dubbed “knuckles” for the role they played in connecting parts of the bridge. They await a new purpose. Nearby a 400-foot-long retaining wall is built from cut-up segments of the bridge decking. The pattern of exposed steel mesh is recognizable to people who walked or drove over the early bridge. Chunks of ragged asphalt still cling to the now-vertical panels of decking steel and concrete. It is a perfect use for the old roadbed.

Given the long history of connecting Juneau and Douglas, perhaps residents should be considering locations for the third crossing instead of the “second crossing.”