Two weeks ago, as nighttime temperatures dipped into the teens, the city condemned the Bergmann Hotel and evacuated 30-some tenants from the dilapidated building. Now that the weather is beginning to warm up, it might be water under the bridge for some — but questions persist as to how the boarding up of the Bergmann was handled, and even as to whether it was necessary at all.

On March 9, city officials had issued a 24-hour “notice and order of dangerous building” that listed violations that were creating an unsafe and unsanitary situation that made the premises “unfit for human occupancy.”

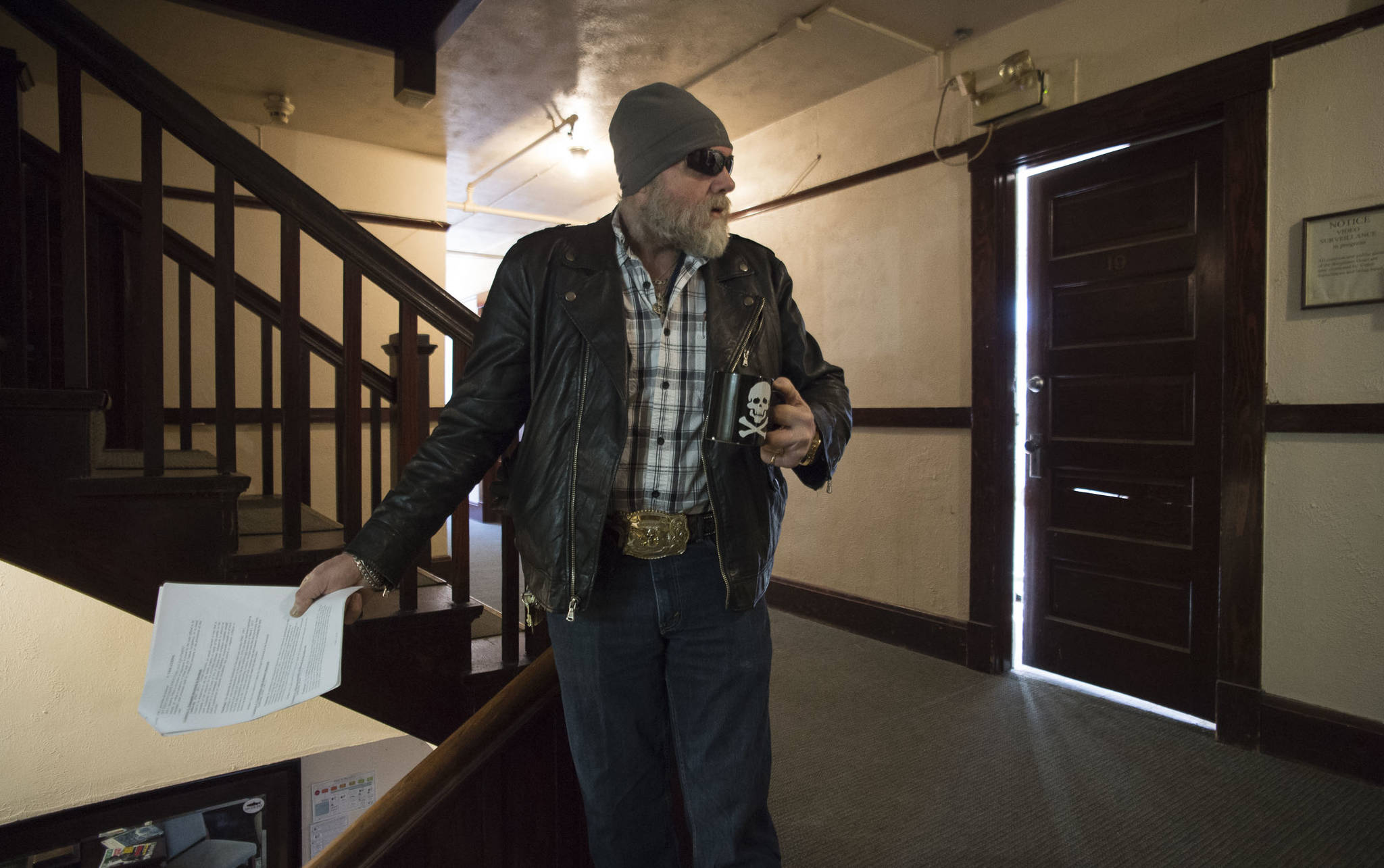

The order says the building had to be vacated within 24 hours, regardless of whether the violations were corrected. And that’s how it was handled, with the building getting shut down and condemned and with the arrest of building manager Charles Cotten because he did not vacate the building.

But Cotten says he was told the Bergmann Hotel could stay open, as long as they fixed the most egregious issues.

And that was the message the city was sending out, as late as noon that Friday.

On March 9, City Manager Rorie Watt sent a release to the Empire that stated the City and Borough of Juneau issued the owner of the Bergmann Hotel, Kathleen Barrett, and Cotten a notice of code violations and an order to evacuate the building, citing significant health and safety issues.

According to Watt’s email, Barrett was given 24 hours to rectify the violations.

“If she fails to do so, CBJ will be forced to close the building and tenants will have to be evacuated mid-day Friday,” he wrote.

“In the event that the building has to be evacuated, CBJ is working with The Salvation Army and partner social service agencies to connect displaced tenants with housing and resources,” Watt concluded.

The following day, just hours before the deadline, CBJ Deputy City Manager Mila Cosgrove told the Empire there would be another walk-through before a decision to close the building down would be made.

But at 4 p.m., that decision appeared to be a done deal. City officials and Juneau Police Department officers walked through the door, telling tenants the building had been condemned and they needed to clear people out. Cotten was detained, Police Chief Bryce Johnson said, because the hotel was supposed to have been vacated by then.

A last walk-through then was conducted with Kathleen Barrett’s son, James Barrett; Capital City Fire &Rescue Fire Marshal Dan Jager later cited unsafe carbon monoxide levels found in the boiler room as the tipping point.

“We were working on the issues when they got there (at 4 p.m.),” Cotten said. “We were told they would re-inspect … and if we weren’t up to par, they were going to close it.”

But that’s not what happened, he said.

“Had I known, would I have left my stuff there?” Cotten asked. “I have an antique desk and a $1,000 fridge still sitting there. … They closed it down under deceit and deception.”

Plan in place to safely house displaced residents?

Questions have also arisen about the city’s handling of the looming displacement of the hotel’s tenants.

While a sign had been posted on the exterior of the hotel on March 9, few tenants seemed aware of the 24-hour notice and believed they might be able to stay.

Some service agencies that were cognizant of the developing situation went door to door Friday morning, talking to clients, and made plans to show up and possibly provide transportation if tenants were displaced later that day.

Cosgrove said that CBJ was “attempting to create a safety net for tenants,” and had worked with the Salvation Army to open a low-barrier warming center for a few nights. She added that city staff would be on site and that flyers would be handed out.

A city official was outside above the hotel at the corner of Third and Harris streets with those flyers, but it was not clear how many tenants got one. The flyer stated that AWARE, Glory Hole and St. Vincent de Paul were available to help.

The flyer then listed the Glory Hole for anyone needing immediate housing. Earlier that day, however, Glory Hole staff going door to door had informed tenants that the shelter had been at maximum capacity the night before. The next option provided on the flyer was the Salvation Army’s warming shelter, but no plan was in place for transportation until volunteers from St. Vincent de Paul, AWARE and the Glory Hole showed up on their own initiative.

Cynthia Dau, a concerned Juneau resident who showed up at the Bergmann that afternoon to lend a helping hand, later emailed members of the Assembly regarding what she described as a “gut-wrenching” failure to handle the situation humanely.

“You knew the owners,” she wrote. “You knew the circumstances. This is not a population that responds to hit-or-miss contact. Anyone with strength of mind would have insisted on person-to-person contact” by knocking on tenants’ doors.

City manager Watt, however, placed the blame squarely on the building owner and manager, arguing that it was unfair to criticize CBJ’s handling of the situation.

“It’s not right to come in after the fact and criticize the city for playing the hand that the owners dealt,” he said.

“There is one group that could have avoided the whole situation — the building owners,” Watt charged. “They put the tenants and the city in this position, and the service providers. It could have all been avoided if they had just taken care of that building instead of blaming everyone else for what came after.”

Housing is a big goal of the city, Watt said, adding that having to condemn the Bergmann shows how dire the situation was.

“I don’t think anybody is very happy we had to take that action,” he said. “It’s incredibly disappointing.”

Watt said he was not aware how long the most egregious issues, including a hole in the roof, had been present, but said the building owners’ refusal to correct the code violations on the city’s mandated timeline is what precipitated the decision to post the 24-hour notice.

“The owner was not being responsive,” he said. “You have this 100-year-old building with a hole in the roof and an ad-hoc heating system … The fire danger is really, really high.”

Watt cited the December 2016 Oakland warehouse fire that left 36 dead as the kind of outcome he wanted to prevent, saying, “You can’t prove the negative of what could have happened.”

Code violations included broken windows, unsafe boiler, damaged sheetrock

From the city’s perspective, the Bergmann Hotel management staff had been given numerous opportunities for the violations to be repaired.

In a release sent out after the building was shuttered, spokeswoman Lisa Phu noted that a letter requesting the correction had been sent in October, with a Nov. 18 deadline.

“At Barrett’s request, the deadline was extended to the end of February,” Phu wrote. “In the interim, CBJ and CCFR officials did repeated walk-throughs and communicated with Ms. Barrett and building staff on multiple occasions. Inspections in March revealed few corrections and several new violations.”

According to CBJ, those issues included a lack of heat, lack of bathrooms, lack of fire protection, the hole in the roof and old wiring.

Hours before city officials condemned the building, Cotten conducted a quick tour of the three-story hotel.

A dangerous building, Cotten said, is “one where you might fall through the floor, or something might fall and hurt you.”

In his estimation, there wasn’t any such danger.

“There is nothing life-threatening about the stuff that you’ve seen,” he said. “It never gets down to a dangerous temperature in this building. If the boilers go off, we get them fired up. They were off only when we were working on them.”

Down in the basement, Cotten pointed to piles of stored items, none of which are currently blocking the sprinkler heads.

“The stacks used to be up to the ceiling when I first started working at the Bergmann,” he said. “I think we’ve done pretty good; we’ve taken out three dumpster loads since then.”

In the boiler room, Cotten said, the pressure valve on the boiler kept blowing, causing hot water to be discharged. He blamed wind outages for the problems they had been having with keeping the boiler lit.

According to Cotten, a damaged sprinkler head was quickly fixed, although he did not have the system certified as was mandated by the city.

There were operational bathrooms, mostly separate toilets and showers, on all three floors, but not in the basement; according to Cotten, those were deemed unnecessary because there is no longer any public access to that area.

Cotten said he had just had all the fire extinguishers serviced, but that three were subsequently vandalized and needed to be re-charged. The fire exit door also keeps getting damaged, he said.

“We can only do so much — we can’t walk the halls constantly,” he said.

Cotten acknowledged the missing skylight was a major issue, but claimed it was being fixed.

Kathleen Barrett’s son, James, who was handed the keys to the hotel last week, said fixing the missing skylight would be a simple fix as soon as the weather warmed up. He pledged to get the Bergmann up and running again as soon as possible.

On Friday, however, little sign of progress could be discerned, with no one present at the hotel and some sort of alarm persistently going off. It could still be heard Saturday morning.

• Reporter Liz Kellar can be reached at 523-2246 or liz.kellar@juneauempire.com.