Not many groups of young people thrown together under circumstances generously considered adverse will reunite again after five years, much less 40. But nothing could be further from the truth, including a functioning generator and running water, for members of the False Island Young Adult Conservation Corps (YACC).

“We might have been the most remote YACC Camp in the country,” said Lisa Louie, the first director of the camp.

Located roughly 30 air miles from Sitka, the False Island YACC camp was located on the southern tip of Chichagof Island in a former logging camp left to rust after that area of the island was clear cut. The camp was considered at least derelict when the program started in January 1979. The camp ran from early 1979 to 1982.

“We took over the old logging camp and it was a disaster,” Louie said.

A former firefighter and member of the California Conservation Corps at its founding, she transferred to Alaska to be the on-the-ground director of the YACC False Island camp. There was no running water, the generator was so dangerously broken that the Forestry Service once ordered the camp evacuated, and there was refuse and waste strewn everywhere from the loggers.

“We took something run down and terrible and made it work,” she said. The former corps members celebrated their 40th reunion Friday, July 19, at Eagle River United Methodist Camp outside Juneau with camping, food and reminescence.

According to Jane Cavello, team leader with the False Island YACC Camp, about 221 people cycled through the camp, both management staff and enrollees, mostly young people working for $3 an hour in one of the most remote places in the United States.

“The YACC camps were aimed at hiring local youth,” Louie said. “That didn’t work in Alaska.”

False Island YACC camp was one of three YACC camps in the area, and the only one to remain in operation beyond its first year.

“That was the magic of False Island,” Cavello said. “People came from all over, poor families and wealthy families, into really harsh conditions, and made it work.

James Miller was another corps member at False Island in 1981.

“It’s all about teamwork,” he said. “People didn’t walk away here. People jumped in.”

Corps members learned to log, debark trees and scribe them cleanly so they would stack neatly without any need for chinking, said Cavello. When an improvised hot water heater made out of an oil drum was deemed too dangerous, they replaced it. When they need to store wood for the long winters, they built a storage building out of logs.

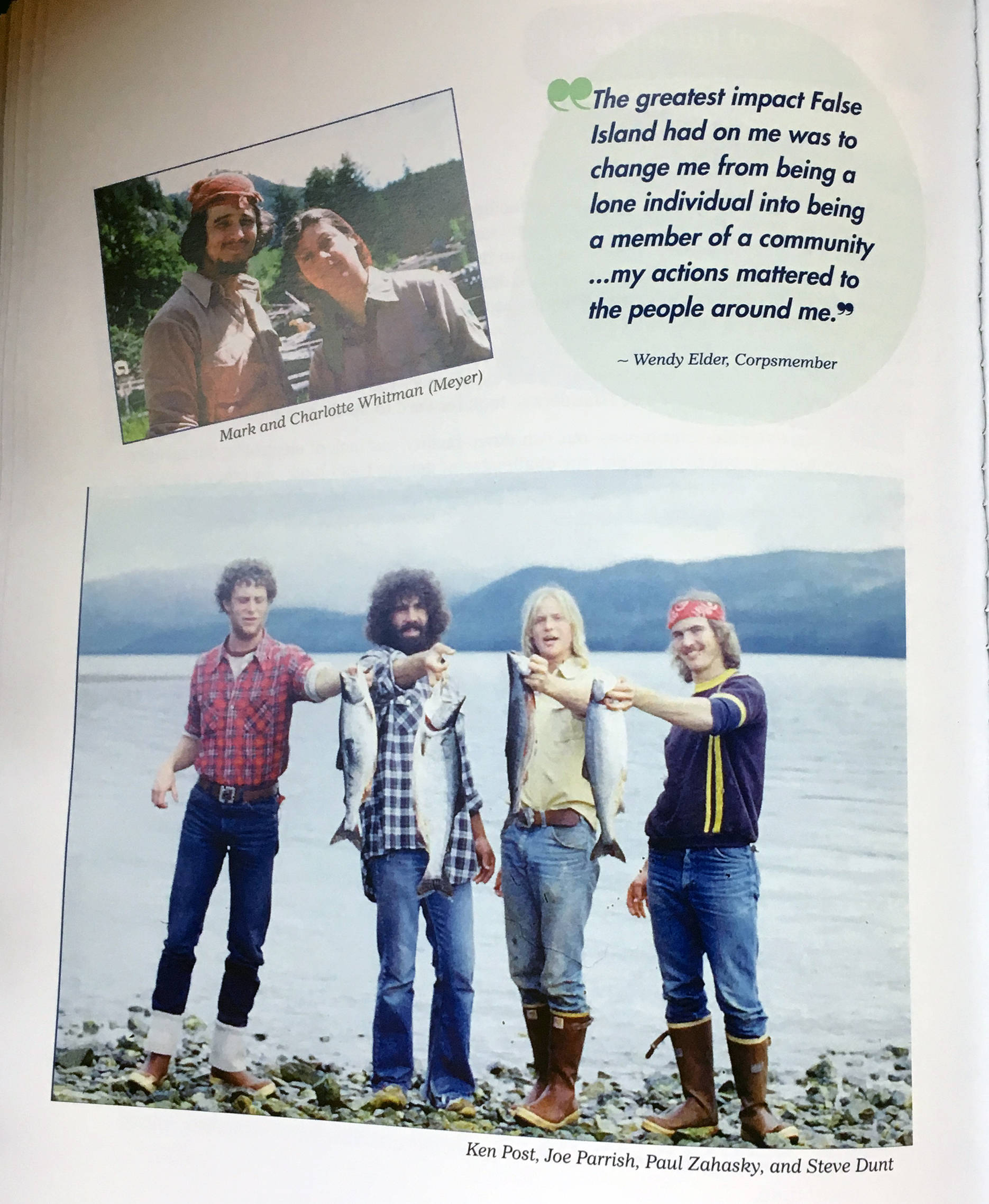

“We’ll build a dam. We’ll build a garden. We’ll do it,” said corps member Mark Whitman. Many members still live in the area, though many also traveled from their homes across the country to be here today.

And the conditions were bad. When members arrived at the camp in 1979, there was no power, no water — hot or cold — and no easy resupply. Everything had to come via seaplane, helicopter or boat. Crews would go out on projects planting trees, clearing trails and unblocking streams, among other things, for 10 days at a time, rotating back to camp for four before going back out again.

“One crew got stuck without food for four days,” Cavello said, recalling a team that was unable to get resupplied due to inclement weather. Other teams — or the camp — would be inaccessible due to the vagaries of wind, wave and tide. Through it all, they persevered.

False Island shut down in 1982, with the nationwide closure of the Young Adult Conservation Corps. Federal budget reductions saw its budget eliminated and much of its work was handed over to contractors doing largely the same thing for considerably more money, said Louie.

“False Island closed well before it should have,” she said. “There’s a lot to be said for putting young people to work doing meaningful work.”

Temporary volunteers returned to their lives, having been changed forever, and the Forestry Service employees moved on to other projects.

In the end, they have the memories and each other. This year marks the 40th anniversary of the camp’s opening, and dozens and dozens of people still attended. For those that had the fortune to work at False Island, it seems to be something that changed their lives permanently.

“It was the people that really wanted to be there. It was unlike any traditional Forest Service crew,” Louie said. “It was from the sense of adventure.”

From all that it was called False Island, there could have been nowhere more true.

• Contact reporter Michael S. Lockett at 523-2271 or mlockett@juneauempire.com.