Whether Alaskans are for or against a ballot measure to increase taxes on North Slope oil production, economists Monday asked people to think about the industry long term when they go to the polls next month.

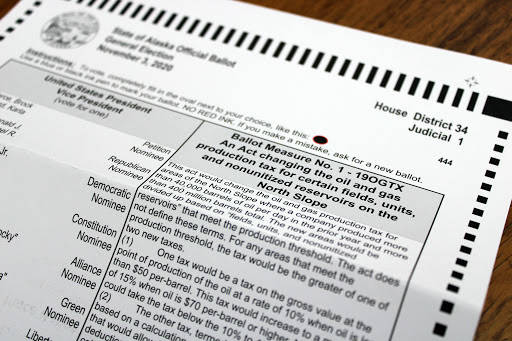

Four economists, all but one based in Alaska, debated the merits of the proposed Ballot Measure 1, officially known as “An Act changing the oil and gas production tax for certain fields, units, and nonunitized reservoirs on the North Slope” but better known as the Fair Share Act, during a virtual forum with the University of Alaska Anchorage.

While millions have been spent on the advertising campaigns for and against the measure, economists struggled to concretely answer the question of what will actually happen if the taxes went into effect, in large part because there are so many moving parts.

“There are different time horizons,” said Mouhcine Guettabi, Associate Professor of Economics at University of Alaska Anchorage’s Institute of Social and Economic Research, which hosted the event. “How much of an effect (the measure has) depends partially with what the state decides to do with the money.”

Guettabi, who said he had no stance on the measure, said over the past few years the state has been using money from savings — the Permanent Fund — to fill the holes in the state budget but also to pay Permanent Fund Dividends. But drawing down savings to pay for both those things is “unsustainable,” he said. Alaska’s budget, he said, “is very much in need of new revenue.”

Opponents of the measure argue that raising taxes on the oil industry, even before the economic downturn caused by the coronavirus pandemic, would decrease investment and lower production leaving the state with little to tax.

“Capital is fluid,” said Roger Marks, an independent economist based in Anchorage. “Oil is a resource that depends on economic expectation.”

Marks said one of his biggest complaints with the yes campaign was what he called, “egregious representations about North Slope profitability.”

[Opinion: The Fair Share Act has a data problem]

Producing oil on Alaska’s North Slope is particularly expensive, Marks said, given the remoteness and harshness of the environment, and companies working in Alaska already pay higher taxes than they do in the Lower 48.

“We have to think about competitiveness and how it would manifest itself,” he said. “Right now, under SB21, they’re paying more than most of the lower 48 states. Producers would have less money to invest, shift investments, there would be incentive to keep production low to avoid (taxes).”

But before Alaska can figure out how much it wanted to tax its oil industry, it needs to figure out what the state is going to look like without the oil industry altogether.

[Election update: Nearly 2,000 more votes counted in local races]

“Where are you trying to get at, what is the endpoint, that should inform what you want to do,” said Nikos Tsafos, energy analyst and senior fellow at the Washington, D.C. think tank, the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

The investor community is moving away from energy, he said, which is leaving oil states with two options. The first is to try to produce every last bit of oil a country has access to, a tactic taken by Saudi Arabia, he said.

The other option was to “skate to where the puck is,” and try to squeeze what remains of the old industry and use the profits to invest in new ones. However, he said the worst thing a state can do is “squeeze” and then not spend the money properly.

Tsafos, who said he has no opinion on the measure, noted the energy market is declining and that investments made today won’t pay off for a long time.

“You go to an investor and say, ‘I want to invest in a sector that’s declining,’ we haven’t seen how those pressures are going to play out in the long term,” Tsafos said.

Most other oil states had nationalized their industries and later brought in private industries, he said, but deciding what is an equitable distribution of state-owned resources has always been contentious and difficult.

“The desire to get the best share has starved the sector,” in some cases, Tsafos said.

While agreeing the economy is moving away from oil, University of Alaska Fairbanks professor Doug Reynolds said the world is going to be dependent on oil for some time, and while there may be a temporary retraction in investment, someone will eventually come for the oil.

“They’re saying they’re not going to invest but eventually they will invest,” Reynolds said. “We’re going to be dependent on oil for a long time. (The North Slope) will get developed eventually, technology will cause costs to go down. (The tax) is not going to ruin the industry, it’s going to be there for a long time.”

Reynolds, who supports the measure, cautioned against the rhetoric of industry collapse.

“I went to the Soviet Union when it was the Soviet Union, I understand what collapse is all about,” he said. “It’s not about fairness, it’s about maximizing value, that’s what all the countries do. You’re not necessarily going to get maximum employment (in the industry), but you don’t want to depend on the oil economy.”

Marks, however, objected to how the word “fair” was being used by the yes campaign.

“The term ‘fair’ has been hijacked,” he said. “Let’s think about investment that’s not happening here, BP left. The issue is how much more do they want to invest, given their opportunities elsewhere.”

• Contact reporter Peter Segall at psegall@juneauempire.com. Follow him on Twitter at @SegallJnuEmpire.