By Becky Bohrer

Associated Press

As partisan warfare has become the norm in state legislatures and Congress, Alaska is set to embark on an experiment to see if voters themselves can disarm the combatants.

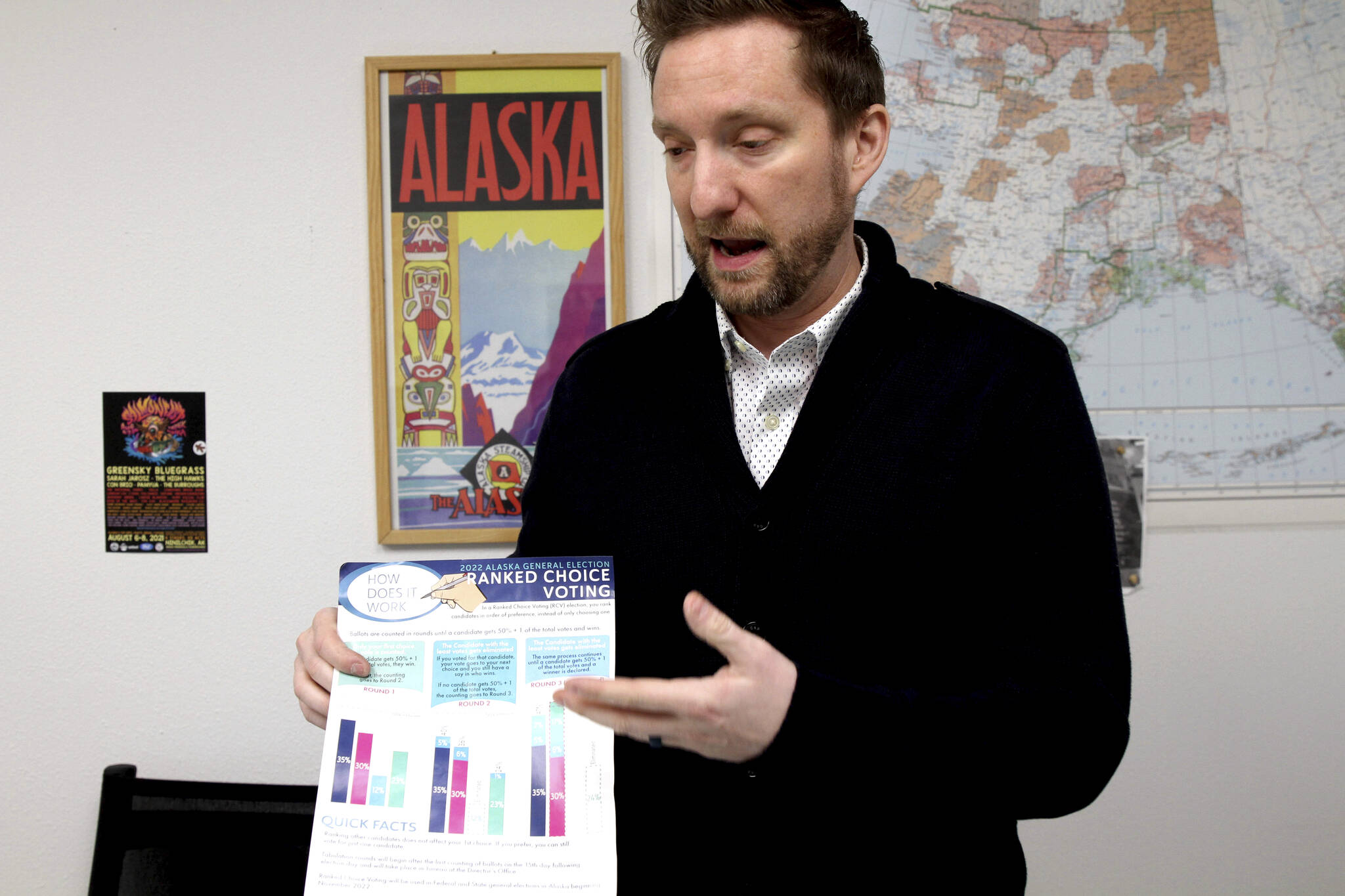

A new election system, narrowly passed by voters in 2020 and set to be used in this year’s races, is aimed at getting candidates to appeal to a broad range of voters beyond their traditional base. The system would end party primaries and send the top four vote-getters, regardless of party affiliation, to the general election, where ranked-choice voting would determine a winner.

The model is unique among states and viewed by supporters as a way to encourage civility and cooperation among elected officials. A sponsor of the initiative, Republican-turned-independent former state lawmaker Jason Grenn, called Alaska a test case “in a major way” for similar efforts being considered in other states, including Nevada.

He said the new system will reward candidates who are willing to work with others, no matter their party affiliation, and that voters will be “empowered in a different way.”

“We’re excited that Alaska gets to lead the way on something that we feel is really monumental towards changing the way voters act and candidates act in our political system,” Grenn said.

For the changes to kick in, they must survive a challenge before the Alaska Supreme Court, which will hear arguments on Tuesday.

Critics are challenging the measure’s constitutionality and allege that it would dilute the power of political parties. A state court judge last year upheld the new system.

This year’s midterm ballot will feature races for U.S. Senate, the state’s lone seat in the U.S. House of Representatives and governor. And under a new redistricting plan that also is the subject of litigation, all but one of the legislature’s 60 seats is up for election. All will be subject to the election reforms if the high court allows them.

Scott Kendall, an attorney who helped write the ballot initiative, said working across party lines seems to be part of Alaska’s “political DNA.” He cited as an example the late Republican Sen. Ted Stevens, who once said his motto during his decades in Congress had been “to hell with politics; just do what’s right for Alaska.” One of the state’s current U.S. senators, Republican Lisa Murkowski, also is known for being able to work with Democrats on some issues and occasionally bucks her own party.

Kendall said he sees the potential for new legislative alliances and coalitions under the system and for those to become more of the norm. A reliably Republican or Democratic district isn’t likely to flip, but the kind of lawmaker elected to represent that district could become more collaborative, he said.

“I think it’s actually going to punish people when they are obstructionists just for the sake of obstruction,” he said.

Harlow Robinson, a self-identified nonpartisan, said he is not heavily involved in politics but volunteered in support of the campaign for the election initiative. The Anchorage resident said partisanship has made government in general “dysfunctional” and hopes the new system provides more middle ground.

He said he likes the idea of coalition governance. But he said there’s nothing wrong with Republican or Democratic majorities “so long as those elected officials are willing to compromise and represent the wider swath of Alaskans.”

Alaska lawmakers have a history of crossing party lines to form majorities in the state House or Senate, in contrast with most other states where the majority party rules with little or no input from members of the minority party. Between 1993 and 2016, governing majorities generally favored Republicans, sometimes heavily, according to a Legislative Research Services report. Rural Democrats in the state have often joined majorities to ensure their constituents’ needs are heard.

An exception to the Republican grip on power came between 2007 and 2012, a period that included a 10-10 split between Republicans and Democrats in the state Senate, adoption of a new oil tax system under then-Gov. Sarah Palin and a windfall in oil revenue. During that era, Democrats held an edge in the majority coalitions alongside as many as six Republicans.

In 2013, after Republicans reclaimed control of the chamber and with Republicans leading the House and in the governor’s office, oil taxes were rolled back. Since then, Senate majorities have been largely Republican.

As lawmakers struggled with deficits following a tank in oil prices, long-time Republican-led control of the House gave way, starting in 2017, to a series of coalition majorities predominantly comprised of Democrats, even as Republicans were elected to a majority of the seats. The number of Republicans who have been part of the coalitions, however, has fallen from as many as eight in 2019 to just two in the current legislature.

The House has struggled after the last two election cycles to organize a majority, similar to political dynamics that play out in other countries. That has made governing difficult — for example, the chamber took a month to elect a speaker in 2019 and nearly as long last year.

Republicans who joined Democrats and independents as part of a coalition in recent years have faced backlash from within their party. Many of them have been censured, labeled turncoats or lost primaries.

Grenn, who served one term in the legislature, said party primaries the last four years have been used as a “weapon” to punish lawmakers who have worked in a bipartisan fashion or who don’t vote in lockstep with their party platform. The new election system would promote working together, he said.

“Now … as opposed to worrying about my primary and having someone outflank me on the right or the left, now I can think about good policy because I will be rewarded for that,” he said.

Former Alaska state Senate President Cathy Giessel plans to run for the Senate again this year after losing a Republican primary in 2020. She said she believes her work across party lines and that of another Republican senator was a “major part, possibly the only part of the reason that we lost reelection.”

Giessel initially opposed the election reforms and was concerned about ranked-choice voting, a system in which voters rank candidates by order of preference and a consensus winner is selected if no one wins more than 50% of the first choices. Giessel said her concerns have eased after she has learned more about the system, which also has been used in Maine.

Giessel said she thinks the open primary “is going to more accurately result in a representative republic form of government in Alaska.”

Lance Pruitt, a Republican who narrowly lost his Anchorage House seat to a Democrat in 2020, questions whether the new process will play out as supporters believe it will.

“The reality is, if this was a solution and everything was going to be hunky dory and it’s all get along and in the middle, then redistricting would not be an issue. There would not be lawsuits,” he said. “There’s still a recognition that you have people that lean left, right. They have a disposition, even if they say, ‘I’m an independent.’

“It’s a real small amount of people that are swayed every election.”