Alaskans’ rate for chronic hepatitis B is nearly three times the national average, but there are measures that can help better control those infections, according to a new state report.

A bulletin issued by the Alaska Division of Public Health’s epidemiology section reveals that from 2010 to 2020, 1,151 newly identified cases of chronic hepatitis B were reported to state officials. That translates to an annual average rate of 14.2 cases per 100,000 people, compared to the national rate of 5 cases per 100,000 people.

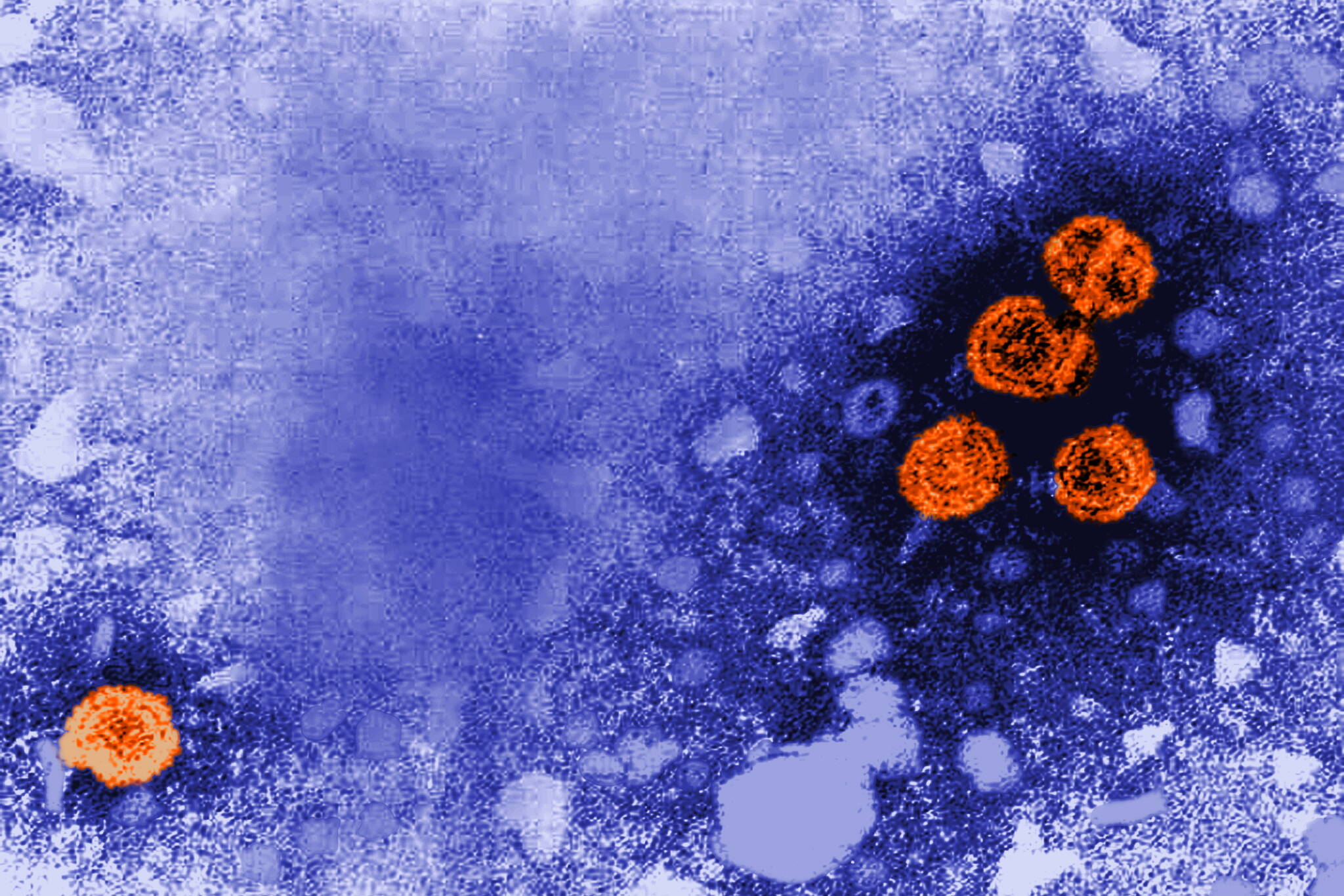

Hepatitis B is the world’s most common serious infectious disease of the liver, and it is caused by one of five hepatitis viruses. Acute cases are those caused by infections that are followed by recovery and resistance to the virus, while in chronic cases, the infectious virus remains in the body. “Some people never get over it,” said Stephanie Massay, a state epidemiology specialist who coauthored the bulletin.

The Alaska records show that chronic hepatitis rates, based on cases identified during that decade, are by far highest among Asians and Pacific Islanders in Alaska. For Alaska Asians, the rate was 69.5 per 100,000, while the rate for Pacific Islanders in the state was 53 per 100,000, according to the bulletin.

That fits with a national pattern. It is estimated that one of every 10 Asian Americans might have chronic hepatitis, likely because of transmission over generations from mother to child, according to the University of California Los Angeles.

Hepatitis B is spread through bodily fluids, and the virus is notorious for its hardiness. If left on a surface outside the body, it can remain active for up to seven days, Massay said. That makes it easier for people who live together to share the virus, she said.

It is not clear why some people suffer only acute infections and others develop chronic conditions, but there are some emerging clues, she said.

“People who are infectious early in life, like during infancy, they’re more at risk for developing chronic infections versus people who get infected when they’re older,” she said.

Hepatitis B, whether acute or chronic, can be avoided through vaccines that are widely used. They have been available since the 1980s and were recommended for children in Alaska since 1991 and even required for school attendance in the state since 2001, Massay said.

A previous bulletin that she authored showed how acute cases of hepatitis B were reduced from the 1980s through 2015 as vaccination became more prevalent.

The higher rates for Asians reflect conditions in countries of origin for immigrants and their descendants, Massey said. In many of those countries, infection rates have long been high and vaccine availability can be low or even nonexistent, she said.

Another way to reduce the spread is to better identify those adults who are carrying the virus without their knowledge, which is a common phenomenon, she said.

The bulletin urges Alaska medical providers to follow a new U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendation for adult hepatitis B screening. That CDC recommendation was issued in March; the Alaska epidemiology bulletin’s list of nine recommendations starts with advice for all adults to be screened at least once during their lifetimes.

Other recommendations are for testing people at risk, including babies born to mothers known to have chronic infections and people who are from countries with high infection rates. While newborns in Alaska are already routinely vaccinated against hepatitis B, those babies born to infected mothers should also get doses of virus-fighting preparations in the first hours after birth, according to the recommendation.

Updated but preliminary numbers of chronic cases are available in a different report issued recently by the epidemiology section. In 2022, there were 119 cases of chronic Hepatitis B that were reported to state authorities, according to the epidemiology section’s 2022 annual infectious disease report, released on Dec. 7. About half of the identified cases were in Anchorage, according to that report, while nearly 60% of the cases identified from 2010 to 2020 were in Alaska’s largest city.

The annual report also contained the number of chronic hepatitis cases identified in 2022 of another strain, hepatitis C. There were 714 identified cases of chronic hepatitis C last year, with nearly 40% of those in Anchorage, according to the annual report.

While hepatitis B is the most common strain of hepatitis infection globally, hepatitis C is more common in the United States, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

There is no vaccine for hepatitis C.

• Yereth Rosen came to Alaska in 1987 to work for the Anchorage Times. She has reported for Reuters, for the Alaska Dispatch News, for Arctic Today and for other organizations. She covers environmental issues, energy, climate change, natural resources, economic and business news, health, science and Arctic concerns. This story originally appeared at alaskabeacon.com. Alaska Beacon, an affiliate of States Newsroom, is an independent, nonpartisan news organization focused on connecting Alaskans to their state government.