A Juneau attorney has filed a wrongful death suit against the state Department of Corrections in the 2015 death of Joseph Murphy, who was being detained at Lemon Creek Correctional Center on a protective hold.

Murphy’s fatal heart attack while in a jail cell on Aug. 14, 2015, was one of several deaths in Alaska prisons that were investigated and that ultimately led to the resignation of then-Commissioner of Corrections Ronald Taylor.

On Tuesday, attorney Mark Choate filed suit against the state of Alaska Department of Corrections and three employees of the department who were involved in Murphy’s care while he was at LCCC.

Murphy had gone to the emergency room at Bartlett Regional Hospital, seeking treatment for depression and suicidal thoughts, Choate wrote in the complaint. Choate noted that Murphy had sought treatment repeatedly that year for depression as well as for alcohol-related issues and chest pain accompanying alcohol withdrawal.

That day, Murphy was intoxicated, with a blood alcohol content of 0.16 percent, Choate wrote. The emergency department staff determined he needed to be monitored as a suicide risk and discharged him into the custody of the Department of Corrections for up to 12 hours of alcohol detox and suicide monitoring.

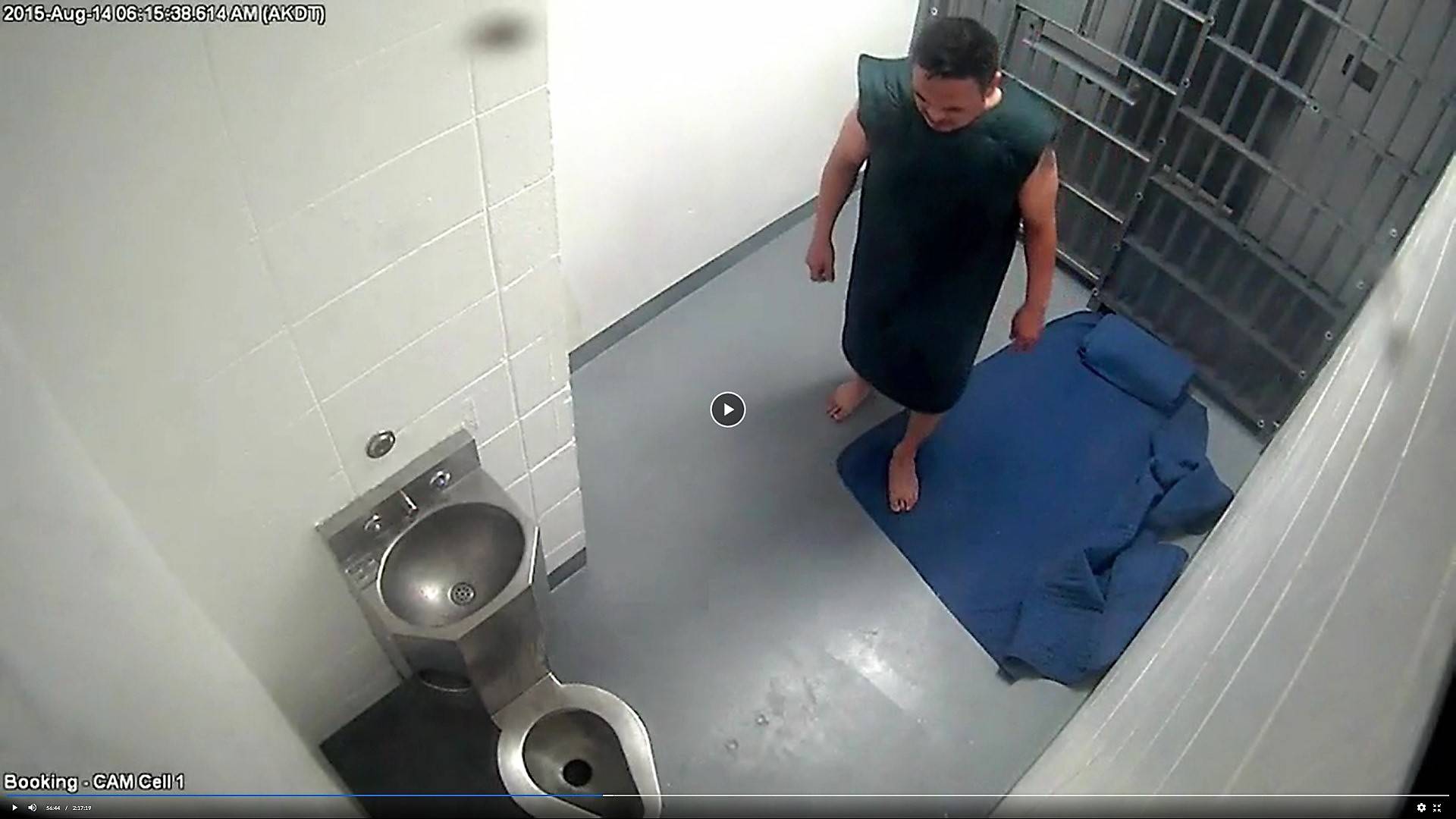

The next morning, less than an hour before his scheduled discharge, Murphy began complaining of chest pain, the complaint reads. According to the complaint, nurse Jill Robinson and correctional officers Michael Schramm and Robert Corcoran ignored his requests for help; Corcoran reportedly was heard telling Murphy he did not care if he lived or died. Murphy subsequently collapsed and died in his jail cell, without anyone noticing for approximately 12 minutes.

“It was a terrible situation, is the only way to describe it, and something that shouldn’t have happened,” Choate said Friday.

“I think the jail … was a terrible place for him,” Choate added. “The jail is a terrible place to be dealing with people who have alcohol issues — detox is a condition that requires medical monitoring.”

“Joe Murphy didn’t go the hospital to die,” he continued. “He went to the hospital to live. They locked him in a place where he could get no medical care. He knew he had a heart condition and he knew his chest was hurting. … And there was nothing he could do because no one was listening to him.”

The four-month investigation by the Governor’s Office in late 2015 that included Murphy’s death found significant problems within the Alaska Department of Corrections, including repeated violations of inmates’ legal due process rights and the holding of drunken and intoxicated people in protective custody for illegal lengths of time; it also was found that investigations of inmate deaths were not conducted properly.

Murphy’s death led to recommendations that the state create an independent internal investigation team outside the Department of Corrections, and that the state “eliminate the practice of admitting intoxicated individuals in prison for protective custody.”

Murphy had been detained at LCCC under Title 47, a statute that allows corrections officers to detain people for their own protection. Under that statute, a person can be held for a maximum of 12 hours or when the person is no longer incapacitated, whichever comes first.

The wrongful death suit filed by Choate on behalf of Murphy’s estate claims a reckless breach of standard of care by a health care provider; reckless failure to train; medical negligence; negligent training; and negligent supervision by the state Department of Corrections. It also claims a violation of the 14th Amendment right to due process by Robinson, Schramm and Corcoran.

“This is a pretty extensive complaint,” Choate said. “We wanted to gather all the necessary information and we ran it by the appropriate medical experts and the experts as to how jails handle medical conditions. It’s an unusual case — we were fortunate there was no statute of limitations.”

Choate said the state of Alaska has statutory caps on general damages; for instance, he said, the cap for general damages due to medical malpractice is $250,000.

But in this case, he said, he hopes to prove that the statutory damage caps will not apply because the conduct by the prison and its staff was reckless, if not intentional.

“We also have federal claims for deliberate indifference and we don’t believe there is a cap on those either,” he said, adding that even through there are federal claims in the complaint, it will be heard in state court.

The three individuals listed have 20 days to respond, while the state has 40 days, Choate said.

Pursuing a case against the state will be expensive and time-consuming to pursue, Choate said, adding, “I am committed to taking this to trial. I believe in the process… I believe it’s important.”

A spokeswoman for the Department of Corrections said Friday that she could not comment on ongoing litigation.

“However, the Alaska Department of Corrections takes every death inside of our institutions seriously, and each case is investigated thoroughly by law enforcement and by our own professional conduct unit,” Megan Edge said.

Edge added that following the Governor’s report, the state created a professional conduct unit to serve as an internal investigation team.

The Department of Corrections still accepts Title 47 admissions, Edge said, “but we are being a lot more selective about who we accept.”

Contact reporter Liz Kellar at 523-2246 or liz.kellar@juneauempire.com.