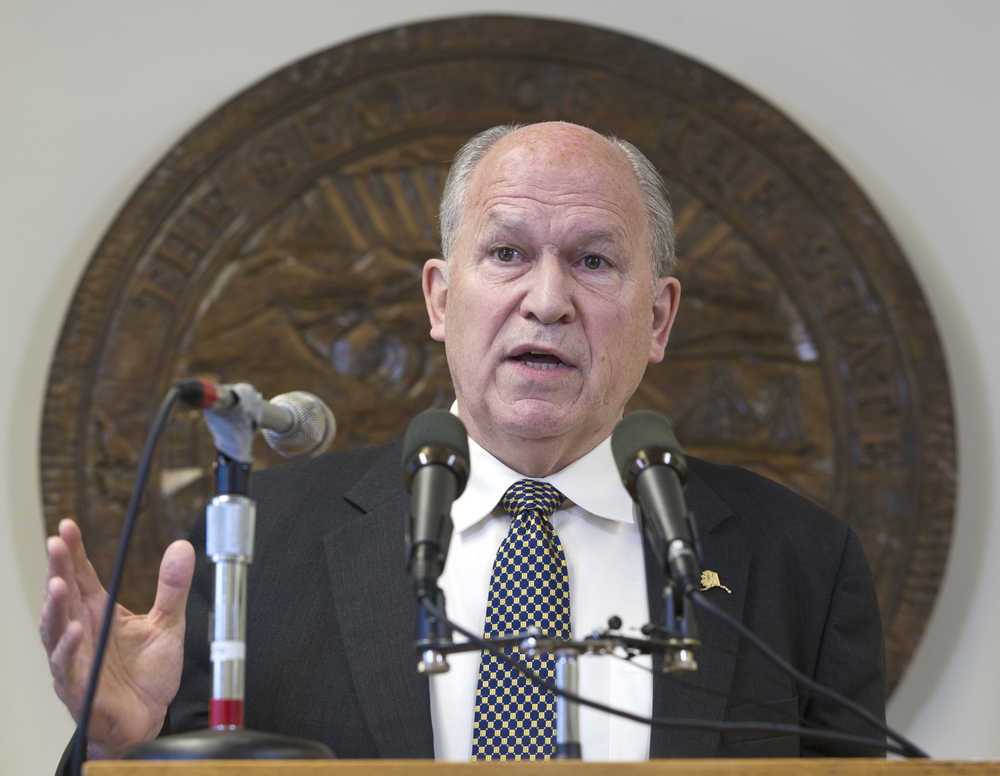

JUNEAU — Alaska’s first independent governor enters the second half of his term with unfinished business: resolving the state’s multibillion-dollar budget deficit.

It’s not quite what the onetime mayor of rural Valdez had in mind when he campaigned for the state’s top job with visions of making a long-hoped-for gas pipeline a reality.

But by the time Gov. Bill Walker took office, oil prices were in a freefall, deepening the deficit he already stood to inherit in a state that relies heavily on oil revenue. Since then, Alaska has slumped into a recession and seen its once-sterling credit rating downgraded.

The pipeline remains a goal for Walker. But he’s also trumpeting another, perhaps more urgent objective: securing a sustainable budget plan that’s not completely dependent on oil prices.

Oil should be a “healthy part” of the budget, but “we cannot tie our state’s future to the price of one single commodity,” the 65-year-old former oil and gas attorney told The Associated Press. “Alaska must diversify its economy and establish sources of revenue that can withstand the life of a finite resource.”

That’s a bold proposition in a state where oil revenue covers a large chunk of the government’s bills and nearly every resident gets a yearly check from its oil wealth fund.

Walker tried to achieve the same goal last year but couldn’t scrounge up enough support for most pieces of his plan, including reinstating an income tax, raising various industry taxes and tapping earnings from the state’s oil-wealth nest egg.

This year, he has so far scaled back. But he’s still eyeing nest-egg earnings and says he wants to bring Alaska’s long-untouched motor-fuels taxes more in line with the national average.

Walker knows his proposals are unpopular but believes he’s doing what’s best for the state. He says he draws inspiration from past governors, like Bill Egan, Jay Hammond and his mentor, Wally Hickel, who “governed with Alaska’s best interests at heart, not their own political capital.”

He said he ran to “fix Alaska,” a job he doesn’t expect to finish by 2018, when he says he’ll probably seek re-election. Walker, described by his wife as someone who rarely takes a sick day, recently underwent what his office said was successful surgery for prostate cancer.

He’s been criticized for not communicating enough with lawmakers but has made an effort to strengthen relationships, joining the legislative bowling league last year and hosting lawmakers at the governor’s mansion.

Incoming Senate President Pete Kelly, a Fairbanks Republican, called Walker a “good dude.”

“But that aside, obviously we fight over important things, and we should fight over them, whether we’re cordial or whether we’re friends or not,” Kelly said.

Clive Thomas, a former Alaska university professor who recently co-edited a book on state politics, credits Walker with engaging in a long-overdue discussion on moving away from a reliance on volatile oil revenue. Similar discussions started in the past when oil prices cratered but generally petered out when prices rebounded, he said.

Still, he’s not sure Walker will get his agenda passed this session.

“I would give it a 50-50 percent chance of anything happening,” Thomas said.

The gridlock that marked last year’s drawn-out legislative sessions tempered Walker’s optimism about reaching an agreement with lawmakers. He began calling the situation a crisis as Alaska drew down its savings to balance the books, and he cut Alaskans’ dividends in half, prompting a lawsuit by current and former lawmakers. Walker won, and an appeal is pending.

He’s hopeful a change in the Legislature’s makeup for the term starting Jan. 17 brings a change in attitude.

The House, long held by Republicans, will be led by a coalition comprised largely of Democrats, formed around a shared goal of tackling the deficit. The Senate remains in GOP hands.

Lawmakers have different ideas on taxes and tinkering with the dividend. Senate Republicans see the continued budget cuts proposed by Walker as too paltry. Senate Democrats and House coalition members want further changes to an oil tax credit program they see as too generous. There’s even disagreement on whether the deficit needs to be filled this year.

The governor’s latest plan would leave a hole of about $900 million, which he said he’ll work with lawmakers to fill on “their terms.”

A we’re-all-in-this-together ethos is central to the governor’s administration and his message as he travels the state trying to convince Alaskans of the need to pull together to weather the current fiscal storm.

Walker changed his party affiliation from Republican to undeclared in running with Democrat Byron Mallott in 2014. He became the first independent governor elected in Alaska, and is the only one currently in office in the nation.

His previous political experience was in Valdez, where he was mayor when Jimmy Carter was president. In the intervening years, he advocated for a gas pipeline project.

Alaskans have long discussed a pipeline as a way to provide energy, create jobs and shore up revenues, but efforts to realize that dream have always sputtered. As governor, Walker brought the latest iteration of the project under state control. But there’s no guarantee it will be built. Lawmakers have become increasingly skeptical of the project, and market interest remains unclear.

Regarding the budget, most people probably agree that Alaska needs a diversified economy that’s not subject to the whim of oil prices, said Rebecca Logan, the Alaska Support Industry Alliance’s general manager.

But that’s a “very long-term goal,” she said, noting a healthy oil industry is important in the meantime.