Two artists who worked in Haines in the 1960s and ‘70s were finally officially recognized for designing the ubiquitous logo for the Central Council of the Tlingit and Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska.

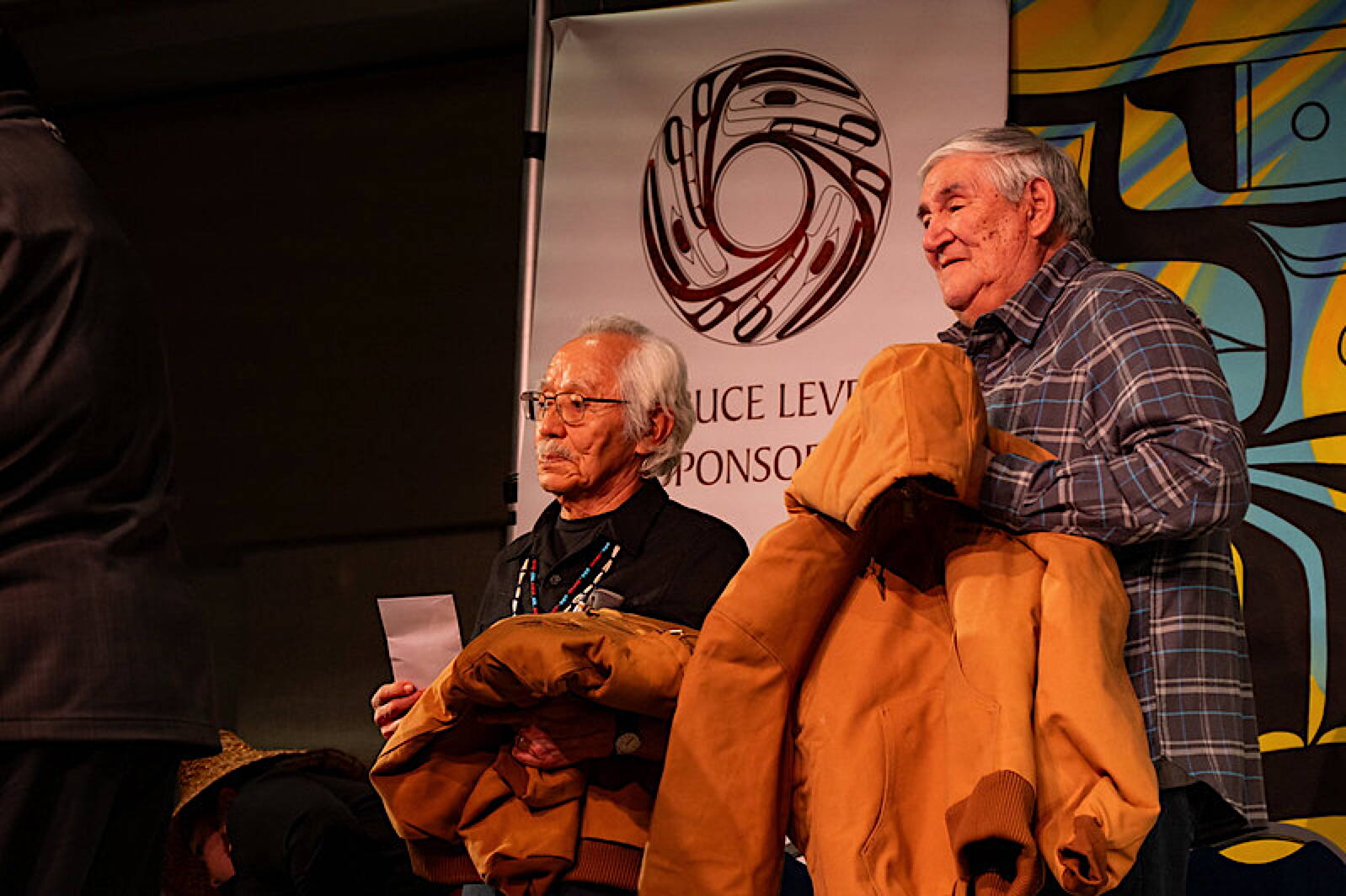

The two artists — Nathan Jackson and John Hagen — were honored at the President’s Awards Banquet in Juneau in front of hundreds of attendees.

“All my kids came to watch,” said Hagen, who is 78-years-old and still lives in Haines. “It was really special to me.”

The design — an intricate formline of a raven and an eagle facing each other — has been on official Tlingit and Haida materials at least since the 1970s. Among Haines artists, it was something of an open secret that Hagen and Jackson were the creators.

“There were a lot of Native people who asked ‘who did it’? I said ‘I did it.’ (Tlingit and Haida) didn’t know till a couple years ago,” said Jackson.

The two artists were part of the Alaska Indian Arts group, which formed around Carl Heinmiller in the early 1960s to revitalize Northwest Coast art in Haines. At the time, the two artists worked in several different media, including carving cedar panels, silk screen printing and block printing.

Jackson, 86, now lives in Ketchikan.

He remembered Heinmiller asking him to make a raven design sometime between 1964 and 1967. He turned to some images he’d found in a book of Northwest Coast art from Wilson Duff, a Canadian archaeologist and collector. Jackson said he learned the craft from Bill Holm, a renowned Northwest Coast art scholar, who identified Jackson’s talent.

“One of the things I understood was that Mr. Bill Holm favored me because I was catching onto formline design,” he said.

After completing the raven, Heinmiller asked Hagen to work on the eagle.

The designs are impressive, said Jenny Lyn Smith, an artist who worked with Jackson and Hagen.

“They’re very good designs — both of them,” said Smith. “If you were studying the art of the Northwest Coast, those would be two that you analyze. They’re very complicated.”

The original designs were made on silk screen with several copies floating around Haines, including two at the AIA headquarters in Fort Seward, according to Lee Heinmiller, Carl Heinmiller’s son.

It was unclear to the artists how Tlingit and Haida started using the design, but artists remember seeing the designs within a few years of when they were made.

“They didn’t rob us right off the bat, but they were using it from us by the early ‘70s, maybe late ‘69,” said the younger Heinmiller.

Heinmiller suspected AIA had sold a cedar panel with the carvings on them, and sold prints made from those blocks. Somehow, Tlingit and Haida got a hold of the designs. Tlingit and Haida didn’t respond to questions before press time.

At the time, the fledgling arts group was struggling to survive. The artists would take fishing or other seasonal jobs to make enough money to eat, since at the time there was little market for Northwest Coast art.

“We almost had to talk people into buying stuff,” said Smith. “We starved one summer.”

The recognition at the awards ceremony went a long way to rectify that, the artists say.

The two artists received a Carhartt work jacket embroidered with the Tlingit and Haida logo, a placard recognizing their contribution, and some cash as a recompense. The two declined to say how much cash they’d received, but “it was sufficient,” according to Dorica Jackson, Nathan’s wife.

Still, they said the recognition from their friends, family, and tribe were far more important than the money.

“I’ve gotten many awards from Sealaska, from Native organizations even on the east coast and Washington, D.C., over a period of time. It makes me feel good to be able to get something from my own organization,” said Jackson.

Tlingit and Haida president Richard Chalyee Éesh Peterson told the crowd at the banquet that he became aware of the issue after visiting Jackson in Ketchikan and was inspired to publicly recognize the two.

“Knowing the truth means you have to act on the truth,” he said.

For Hagen, having his family there was especially important. His son, John, said it was important for his dad.

“I was super excited to see it happen for my dad,” said the younger Hagen. “He’s one of those guys that has never had much recognition for his work.”

• This story was originally published by the Chilkat Valley News.