When a magnitude 7.9 earthquake in the Gulf of Alaska forced weather authorities to declare a tsunami warning for many communities in coastal Alaska, Juneau resident Bonny Hilton Dansie’s phone remained silent.

Electronic notifications went out to cellphones across the state early Tuesday morning, but not all of them. Dansie’s phone wasn’t one of them. Both she and her husband Richard have GCI phones, and neither of them got an emergency alert. The only phone of theirs that did get a notification was one with Verizon service that they hadn’t used in two months.

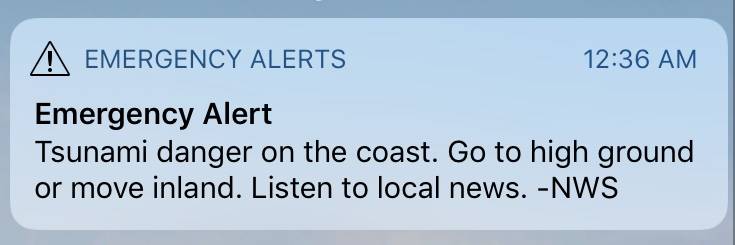

Heather and Richard weren’t the only people in Juneau or Southeast who didn’t receive a cellphone notification. As a result of a complex and long-term process with the Federal Communications Commission, GCI and other smaller providers don’t automatically send federal emergency alerts.

GCI Director of Corporate Communications Heather Handyside explained Tuesday that Wireless Emergency Alerts (WEA) are still at least a few months away for GCI. Getting those alerts set up through the FCC is a long and complicated process, Handyside said, and many smaller providers don’t have the resources to get the system set up quickly.

National providers, such as AT&T or Verizon, were required to have the WEA system set up in 2017. Smaller providers were given an extension until May 2019 to get the system in place. Handyside said GCI will get it off the ground long before that.

“GCI’s been working hard for almost six months now to put the system in place,” Handyside said, “and the good news is we’re only a few months away from being complete.”

In the interim, GCI has set up a free application for iOS and Android phones that can serve the same purpose. The app is simply called GCI Alerts, and Handyside said that GCI customers who had that app downloaded receives an alert Tuesday morning. When the process of setting up the WEA system is complete, Handyside said, GCI will notify its customers.

In general, Juneau is not at great risk for an offshore tsunami. Unlike Sitka, Juneau doesn’t have a siren system for tsunamis because the federal government has concluded that there isn’t a high enough tsunami risk to necessitate having sirens.

A study released in 2017, however, said that Juneau is vulnerable to tsunamis generated by landslides near the shore. These are rare, but when they hit they can form extremely quickly. Local authorities advise that if an earthquake hits Juneau that lasts more than 20 seconds or if it’s strong enough to knock you down, seek higher ground immediately. Offshore tsunamis take longer to make landfall and give people more time to prepare.

[Study reveals worst-case scenarios for tsunamis in Juneau]

‘Feeling pretty good’

Joel Curtis, the warning coordination meteorologist for Juneau’s National Weather Service office, said he had tears of relief in his eyes when he saw reports of how small the waves were after the earthquake Tuesday. He was relieved that there wasn’t a big wave, there wasn’t damage and there wasn’t any loss of life.

The next emotion he felt, as he went through data this morning, was satisfaction that the tsunami alert system had worked well. Alert messages went out to radios and televisions throughout Southeast, he said. Curtis said it will take a while to piece all the data together and make conclusions about how the alert system worked.

“With any large event like this affecting so many people you’re bound to have a few things that didn’t go perfectly,” Curtis said, “but all in all, I’m walking away from this feeling pretty good.”

Curtis said the same of the most recent annual test of the tsunami alert system. In March 2017, NWS ran its usual test of radio alerts, television alerts and sirens. Not everything went according to plan, Curtis said, though he said he couldn’t remember all the details of what went right and what went wrong. When tests don’t go perfectly, he said, it helps him and his team learn from them and address weaknesses.

Dennis Bookey, co-chair of Alaska State Emergency Communications Committee, echoed Curtis in saying it’s still too soon to draw many conclusions about which aspects of the alerts systems worked and which didn’t. There are various alerts systems, Bookey said.

The WEA system, he said, is brand-new technology and he’s most curious to see how that system performed. The Integrated Public Alert &Warning System (known as IPAWS, and operated by the Federal Emergency Management Administration) is in charge of sending out WEA alerts and the Emergency Alert System (EAS) on the radio.

Preparing locally

IPAWS broadcasts on the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Weather Radio network. City and Borough of Juneau Emergency Programs Manager Tom Mattice said in a release Tuesday that NOAA Weather Radio is the best way to stay informed of weather emergencies. These radios are plugged into a charger with a battery providing backup power, and it automatically turns on in the event of an EAS message even if the power is out.

Mattice often preaches the importance of being prepared in advance. Having a “go bag,” filled with survival gear, food, water, medication and other vital items, is the easiest way to prepare prior to an emergency.

While GCI works through the process with the FCC, the duty of signing up for alerts also falls on individuals. Juneau resident Gary O’Halloran was another of the GCI customers who didn’t get an alert. He was sound asleep for the entirety of the tsunami warning, and first thing this morning he took matters into his own hands to make sure that won’t happen next time.

“I wasn’t really surprised I slept through it, but was surprised that I didn’t get an alert,” O’Halloran said. “The first thing I did was get an app that will definitely alert me next time.”

• Contact reporter Alex McCarthy at 523-2271 or alex.mccarthy@juneauempire.com. Follow him on Twitter at @akmccarthy.