By Becky Bohrer

Associated Press

Alaska elections will be held for the first time this year under a unique new system that scraps party primaries and uses ranked choice voting in general elections.

The Alaska Supreme Court last week upheld the system, narrowly approved by voters in 2020.

It calls for an open primary in which all candidates for a given race appear on the ballot, regardless of party affiliation, followed by ranked voting in the general election. No other state conducts its elections with this combination, which applies to both state and federal races.

Supporters hope the new system will help ease partisan rancor and encourage civility and cooperation among elected officials. Critics worry it will dilute the power of political parties, or that minor party candidates will get drowned out. Some are skeptical, too, that the system will work as intended.

A sponsor of the initiative, independent former state lawmaker Jason Grenn, has said Alaska is a test case for similar efforts being considered in Nevada and elsewhere.

Here is a closer look at what’s happening in Alaska:

How does the process work?

In the past, the winners of each party’s respective primary advanced to the general election.

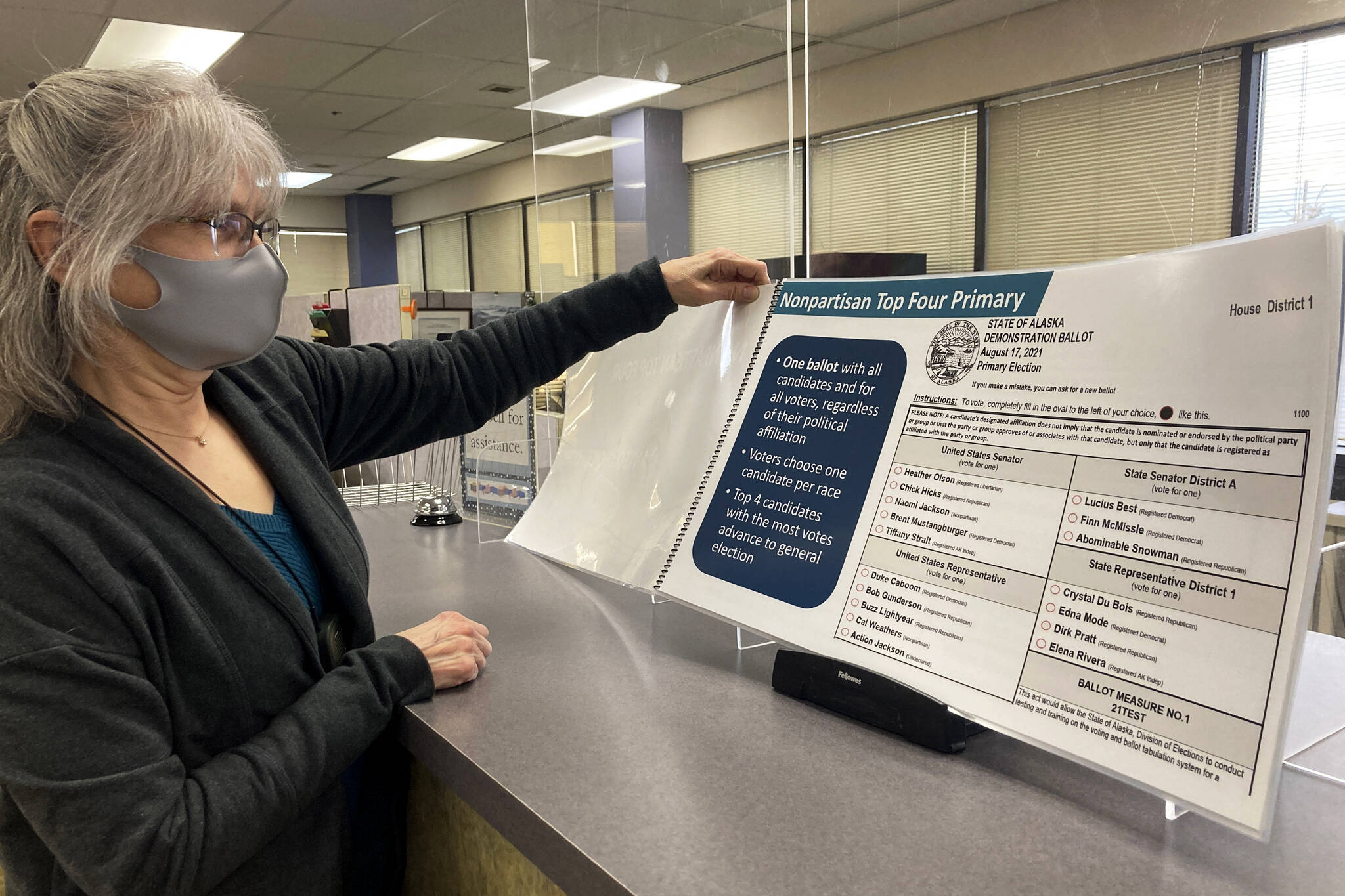

Under the new system, there will be one ballot, available to all registered voters, with each candidate in a given race. The top four vote-getters, regardless of party affiliation, head to the general election. Voters in the general election then can rank candidates by order of preference.

A consensus winner is selected if no one wins more than 50% of the first choices.

Another change: Candidates for governor and lieutenant governor will team up at the outset. Previously, candidates for each office ran separately for the primary, and the winners of each party primary were paired for the general election.

Maine uses ranked voting for state-level primary elections, and for federal offices only in general elections.

Ranked voting is also used in a number of cities for local elections, including New York.

Which races are affected?

All state and federal races are subject to the new rules. That includes this year’s races for U.S. Senate, Alaska’s lone U.S. House seat, its governor and lieutenant governor posts and legislative seats.

Some have seen the system as potentially helping Republican U.S. Sen. Lisa Murkowski, who has a reputation as a moderate and has at times been at odds with Alaska party leaders, including in her criticism of former President Donald Trump.

Murkowski lost her party primary to a tea party candidate, Joe Miller, in 2010 but won the general election with a write-in campaign. She won her primary easily in 2016, the year Trump was elected.

Trump has backed Republican Kelly Tshibaka for this year’s Senate race, and Tshibaka has been endorsed by state party leaders.

Murkowski, in announcing her reelection bid in November, said the strength she offers is that “for me, it has always been about reaching out to all Alaskans,” not just Republicans. She said she hopes one outcome of the system is that candidates might be more civil toward one another.

Why do this?

Scott Kendall, an attorney who helped write the Alaska ballot initiative, said the new system gives voters choices. The reason for ranked voting is to avoid “distorted” outcomes, he said.

If there were four candidates under the prior system, “you can imagine someone winning with 28% of the vote and being a very extreme individual because three moderates over here divvied up the rest of the vote,” Kendall said.

“You don’t want a situation where you get a candidate far outside the norm because a small group supported them. So it’s to get that moderate candidate — prevent the parties from being kind of an artificial gatekeeper to our choices,” he said.

The hope is that more work gets accomplished, particularly in the state Legislature, he said.

The system was unsuccessfully challenged by a group that included Anchorage attorney Kenneth Jacobus; Scott Kohlhaas, a Libertarian who made a failed bid for state House in 2020; Bob Bird, chair of the Alaskan Independence Party; and Bird’s party.

They argued, in part, that candidates for minor parties will “get lost in the shuffle” of names on the ballot. They also said the open primary forces parties to accept candidates they “may or may not want.”