CHICAGO — In this city’s troubled history of police misconduct, Eric Caine’s case may be unrivaled: It took more than 25 years and $10 million to resolve.

For decades, he maintained he didn’t brutally kill an elderly couple. The police, he said, beat him into a false confession. Locked up at age 20, he was freed at 46, bewildered by a world he no longer recognized. Caine ultimately was declared innocent, sued the city and settled for $10 million. But victory brought him little peace.

“They wouldn’t give anybody that large amount of money if they didn’t believe that person was wronged,” he says. “But I also look at it as a way for them to just want me to go away. … Nobody cares if I live or die.”

Caine is just one example of huge police settlements that have tarnished the city in recent years. Among them: A one-time death row inmate beaten by police: $6.1 million. An unarmed man fatally shot by an officer: $4.1 million.

And last year, the family of Laquan McDonald, the black teenager shot 16 times by a white officer, received $5 million. His death, captured in a shocking video, led to a murder charge against the officer, the police chief’s firing and thunderous street protests with calls for Mayor Rahm Emanuel’s resignation.

Chicago has paid a staggering sum — about $662 million — on police misconduct since 2004, including judgments, settlements and outside legal fees, according to city records. The payouts, for everything from petty harassment to police torture, have brought more financial misery to a city already drowning in billions of dollars of pension debt.

The Justice Department’s recent decision to investigate the Chicago police — fallout from the McDonald case — has helped focus new attention on this agonizing history of misconduct and the surprising lack of consequences. Few officers accused of wrongdoing have been disciplined in recent years.

So how did the city get to the point where a massive misconduct bill has almost become routine? And why has bad behavior gone unchecked?

Alderman Howard Brookins Jr. offers one explanation. “If you were seen going after police, you were seen as being for crime,” he says. “Nothing happened to the police officers even after they got a big judgment against them so it appeared to be like Monopoly money.”

Lawyer Jon Loevy noticed the same pattern while winning more than a dozen seven-figure misconduct verdicts over the last decade. Jurors, he says, concluded “police did reprehensible things” — including framing people and shooting them without justification — but he knows of no case where those officers were punished. “Not only was nobody disciplined, nobody was asked any questions,” he says. “It was just back to work.”

Few accusations ever reach the punishment stage, according to the Invisible Institute, a nonprofit journalism organization, and the University of Chicago Law School’s Mandel Legal Aid Clinic. They found that from March 2011 to September 2015, more than 28,500 citizen complaints of misconduct were filed against Chicago police officers, but less than 2 percent resulted in discipline.

Both the police and the union representing rank-and-file officers say the numbers are misleading.

Dean Angelo, president of the union, says criminals routinely file frivolous complaints to harass and discourage police from pursuing them.

City officials also say many complaints are less serious — an improperly issued ticket, for instance. The police, in a statement to The Associated Press, said allegations of misconduct led to 45 firings and 28 suspensions from 2011 through 2015 in a department of about 12,000. Some cases remain open.

During that time, the city doled out tens of millions of dollars on misconduct claims. Only a small number are in the seven-figure range. Stephen Patton, corporation counsel, says his office has cut the number of outside lawyers, taken more cases to trial and since 2011, saved taxpayers at least $90 million by evaluating suits promptly and settling them, if appropriate.

The cost of misconduct, though, extends beyond dollars and cents. It can also leave deep psychological scars.

Ronald Kitchen, who said he was beaten into confessing to several murders, spent 21 years in prison, 13 of them on death row while seven men were executed. “You keep thinking … ‘Is that going to happen to me?’” he says. Kitchen, who was eventually exonerated, settled for $6.1 million.

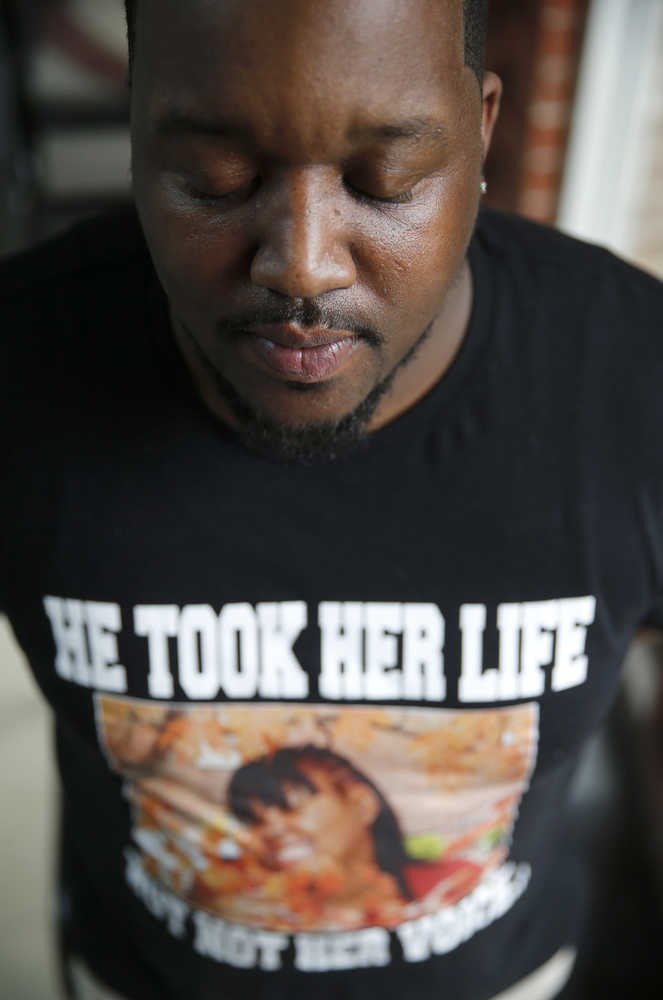

Martinez Sutton says the $4.5 million settlement his family received in the death of his 22-year-old sister, Rekia Boyd, “seems almost like hush money.”

Sutton has been agitating for the dismissal of Detective Dante Servin, who was off-duty when he killed Boyd in 2012. Servin fired several times while sitting in his car after arguing with a group of people. He said he feared for his life as a man pulled an object from his waistband. No gun was found. The man had a cellphone.

Servin was acquitted of involuntary manslaughter last year. Both the Independent Police Review Authority and former superintendent have recommended his firing. The Chicago Police Board will decide.

“It’s a slap in the face to me,” Sutton says. “You can give me money but you still can’t get rid of this officer? It’s not hate against the police department. It’s hold accountable whoever commits the crimes.”

Chicago isn’t the only city with these problems. But the lack of police accountability, a code of silence and racial tensions tend to be more entrenched than in other cities, says Craig Futterman, a University of Chicago law professor.

“It’s not that Chicago is overrun by bad or abusive police officers,” he says, “… but here, a small percentage of officers has been allowed to abuse some of the most vulnerable Chicago residents with near impunity.”

More than 80 percent of officers have fewer than four complaints for the bulk of their careers, he says.

The mayor recently formed a police task force that will create an early warning system to intervene with problem officers. The police statement also said that Interim Superintendent John Escalante is working with others “to review discipline histories, patterns of misconduct, settlements and other information to prioritize investigations and take action where necessary.”

No pattern of wrongdoing has been more damaging than the one involving former commander Jon Burge and dozens of fellow detectives. Scores of black men alleged that over nearly two decades, the officers beat them, played mock Russian roulette and subjected them to electric shocks to secure confessions.

Burge cases — including settlements and outside lawyers — have cost the city more than $92 million, according to Flint Taylor, a lawyer who has spent decades fighting the former commander. Yet only Burge himself was ever charged, decades later — for perjury in a lawsuit when he denied torture had occurred. He was sentenced to 4½ years in prison.

Some critics say the mayor’s vows of reform and the federal probe give them hope this is a turning point.

But Eric Caine, a victim in one Burge case, is skeptical. Five years after his release, he still struggles.

“That 25 years was real hell to me,” he says. “My sense of dignity, my sense of self-worth was destroyed — all shattered, all gone. … Every second, every minute of the day, I think about my mortality.”

He sees little change, noting that it took more than a year for officials to release the McDonald video. “The system is designed to protect itself,” he says. “They continue to do the same thing over and over, instead of doing the right thing.”