It’s pretty challenging to keep up in elementary school when one is learning to read but the letters are backwards, transposed or appear to be out of sequence.

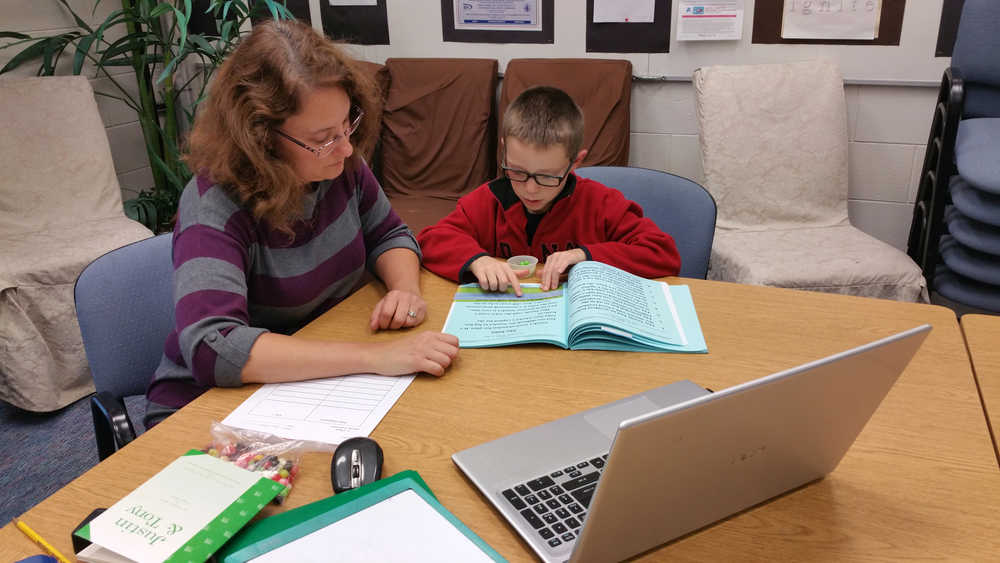

Enter special needs tutor Julee Faso-Formoso, whose own child was diagnosed with dyslexia. She specializes in working with special needs students who have the disorder, which causes otherwise bright and intelligent elementary students to struggle when attempting to read and write.

“I love tutoring kids with dyslexia because while they have difficulty reading and hearing and recognizing sounds to symbol relationships, these kids are very bright, creative and when given a chance, they are willing to share with you what they know,” Faso-Formoso said.

She spends a couple days a week after school at Chugiak Elementary School working with six students whom she sees making academic strides that the additional educational support provided through tutoring can achieve.

Her students enjoy the additional attention.

“I like having Mrs. Julee work with me,” Bruno Pyziak, a third grader. “She understands me. She knows how to help me.”

Faso-Formoso knows it isn’t an elementary student’s first choice to do more schoolwork after a long day of regular education. That’s why she finds ways to break up the monotony with games and rewards for correct answers and encouragement when the right answers are difficult for a student to identify.

“Many of my students recognize how far they’ve come and they get excited about moving from one level to another within the curriculum I use in tutoring,” Faso-Formoso said.

According to the Dyslexia Research Institute based in Tallahassee, Fla., 10 to 15 percent of the U.S. population has dyslexia, yet only five out of every 100 dyslexics are recognized and receive assistance.

Despite the high level of awareness at CES, dyslexia remains a learning disability shrouded in misconception, she said.

“It isn’t about seeing letters backwards, although that is one of its symptoms,” she said. “It’s a neurological disorder.”

The good news, she said, is that “a dyslexic person can be taught to read using direct instruction that is multi-sensory, explicit, structured and sequential in it programming.”

Of course, this takes the amount of work it sounds like is required just listening to that explanation. It cannot all be accomplished by a regular education teacher handling a classroom full of 20 to 25 students all with their own learning issues.

Faso-Formoso said she sees attitudes regarding dyslexia improving.

Acceptance of its specialized academic needs has grown, she said. Recognition that it is a “real” disability has increased as well, she said.

“People realize now that it isn’t a matter of ‘if the student would pay attention in class and try harder,’” Faso-Formoso said.

Her message to people not familiar with dyslexia is that each person with the disorder expresses individually.

“People assume if they have met someone with a particular disability, then everyone else they meet with that disability will be similar,” she said. “Not true. There are ranges of severity in all disabilities.”

Technology plays an efficient role in helping students with dyslexia learn to read and write proficiently, she said.

Text-to-speech and speech-to-text conversion applications provide quick access to language in the format required for whatever assignment the student is completing. The use of audio books that let the dyslexic student hear the words and follow visual images and text help students keep pace with their peers and show competency when tested on materials.

As a special needs tutor and mom, Faso-Formoso is thankful that government officials and federal educators recognize that accommodating the special academic needs of dyslexic students isn’t “caving in” but is instead providing these challenged students with an opportunity to demonstrate just how much information they do understand and giving them an ability to contribute to society as well.

“Laws such as the Americans with Disabilities Act make sure these students are able to receive the accommodations they need once they graduate high school and enter college or the work force,” Faso-Formoso said. “I know the students I am working with now will make a difference in our world.”

• Amy Armstrong is a freelance reporter for the Chugiak-Eagle River Star. She can be reached at amyarmstrong@gci.net or online at facebook.com/pages/Armstrong-Communications-Words-by-Amy-Marie.