July is Disability Pride Month and this year it marks the 33rd anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act, a civil rights law that protects people with disabilities from discrimination. The law preserves their right to access jobs, schools, public transportation and businesses.

But even as people with disabilities celebrate progress, they also say there is still a lot to do. They’re advocating for policy changes to further empower them to have more control about the services they receive.

Many things changed as a result of the Americans with Disabilities Act, according to Patrick Reinhart, executive director of the Governor’s Council on Disabilities and Special Education. He lived in Alaska when the act, known colloquially as the ADA, was passed.

“By making all these businesses and government facilities and educational facilities accessible, it’s opened up the doors for more people with disabilities to find a job, or do whatever they want to do,” he said.

Reinhart pointed out that the council works with the state’s Division of Vocational Rehabilitation to help people with disabilities find the jobs they want. But he also said there’s still a significant employment gap between people with disabilities and those without them.

Policy progress

Reinhart said he’s excited about a bill the governor is slated to sign this Saturday that will allow Medicaid to pay for people with disabilities to have care and support from people within their own households — even their legal guardians or family members, and will also allow the state to license private homes in the same way they would license a care center.

Both changes give people with disabilities more agency to live the lives they choose, he said, by selecting a known caregiver or opting out of an institution.

Michele Girault, board president for the Key Coalition of Alaska, an advocacy group for people with disabilities, applauded the policy progress this last year. One big victory, she said, was the state putting money toward eliminating a wait list for care for people with disabilities. The funding covers the first year of a five-year plan.

“If you have a disability in Alaska, you can’t just go knock on the door of an organization and get immediate services. There’s a process to go through. And it’s a very complicated process,” she said.

She estimated that there are up to 600 people with disabilities on the waitlist.

Girault was also buoyed by $7.5 million in this year’s budget that is aimed at recruitment and retention of staff for people with disabilities. As a result, the Division of Senior and Disability Services increased payment rates for Medicaid home and community-based waiver and state services by nearly 8% at the beginning of the month.

Working to “live normal lives”

Disability rights advocate Ric Nelson wants to see the state go even further toward empowering people with disabilities. He is the founder and executive director of Peer Power Alaska, an education and advocacy nonprofit run by people with disabilities.

“Our main purpose is to train people with disabilities about their rights and services they qualify for,” he said. “We want people to realize that people with disabilities can give back to their communities, and we don’t live off government assistance.”

He said his biggest goal is to get the Legislature to pass a bill that would allow people with disabilities to have “budget authority” — the right to hire their own direct service providers, set the rate they pay them, and waive certain trainings if they’d like to get care faster.

“We have to rely on an agency for help. They tell us what time they’re coming in,” he said of the current system. Budget authority would be a change. “And with this, we can control our own lives,” he said.

Nelson said he has been working toward budget authority in the state for the last two decades. It can take a month for agencies to make a hire, he said, and that’s a long time to ask a caregiver to wait before they start getting paid. He said he’d also like to be able to pay more than the rate agencies pay caregivers.

“It will help people like me live more normal lives,” he said.

Maggie Winston, the program director of the Independent Living Center on the Kenai Peninsula, said the push for budget authority is part of a bigger effort toward what’s called “participant directed services.” In that model, certain people with disabilities could decide which services they need to help them work and have a full life.

Winston said her first identity, before her job title, is as a disabled woman — she has a spinal cord injury that means she has no functional control of her arms or legs, so she uses a wheelchair that she drives with her chin for mobility.

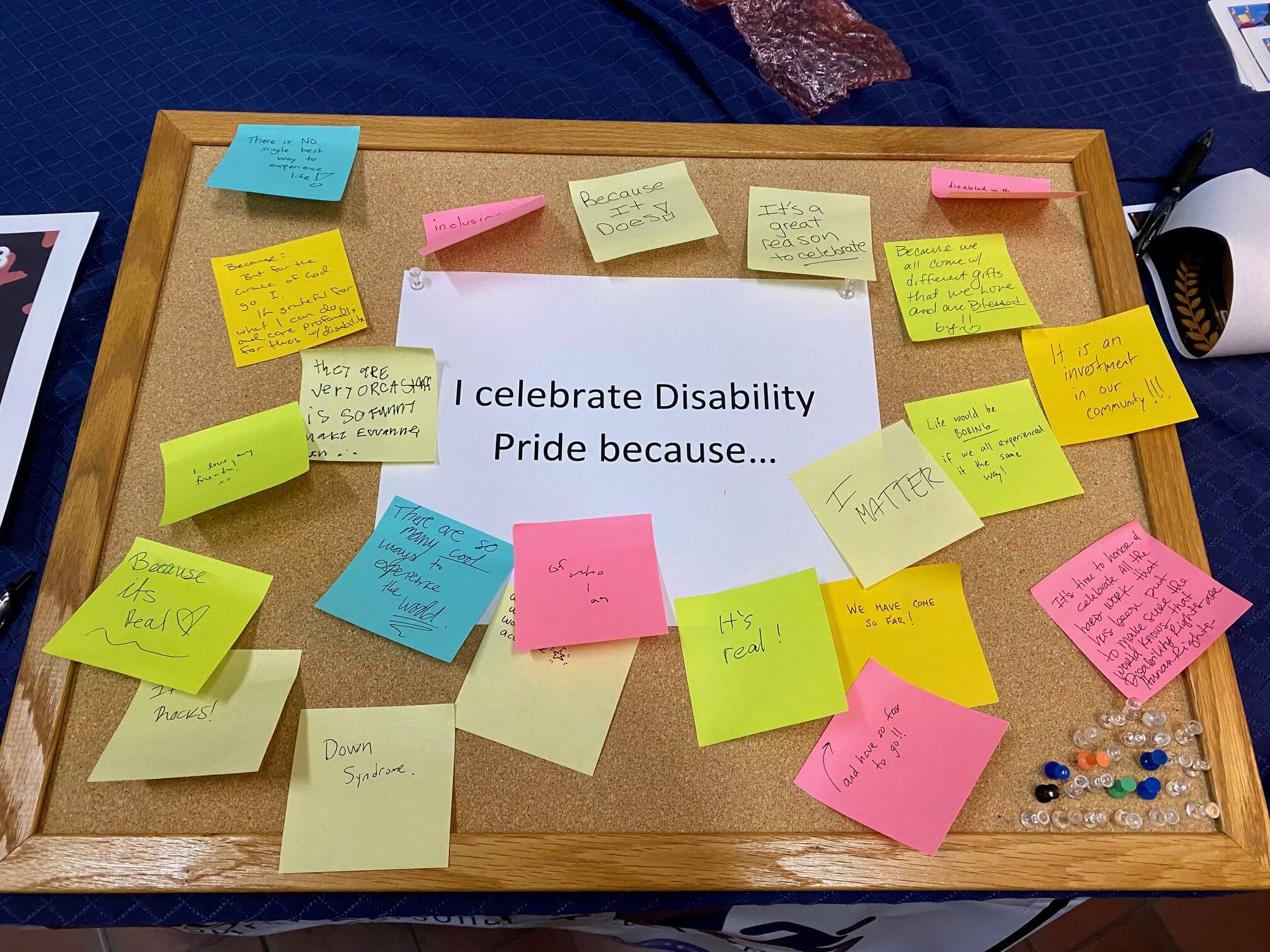

The idea of participant directed services is about agency, and allowing people with disabilities to live lives that accommodate their limitations. Winston said Disability Pride Month addresses what she calls the “social model of disability,” a way of thinking about disability that doesn’t cast the person as a problem.

“Society puts disability on me by denying access,” she said. “Making things accessible to people includes changing your mind about them. And Disability Pride is about helping to change those attitudes.”

More than a quarter of Americans experience a disability; advocates say it’s the nation’s largest minority.

“Disability is a natural part of the human condition,” Winston said. “Anybody can enter this community in an instant. So it’s time that we really start changing minds and attitudes about disability.”

• Claire Stremple is a reporter based in Juneau who got her start in public radio at KHNS in Haines, and then on the health and environment beat at KTOO in Juneau. This article originally appeared online at alaskabeacon.com. Alaska Beacon, an affiliate of States Newsroom, is an independent, nonpartisan news organization focused on connecting Alaskans to their state government.