The Bureau of Land Management issued a draft environmental assessment Friday along with a finding of no significant impact for roughly 28 million acres of land for potential selection by Alaska Native veterans of the Vietnam War era.

In a news release, the bureau said the assessment looked at opening up an additional 28 million acres of land for selection.

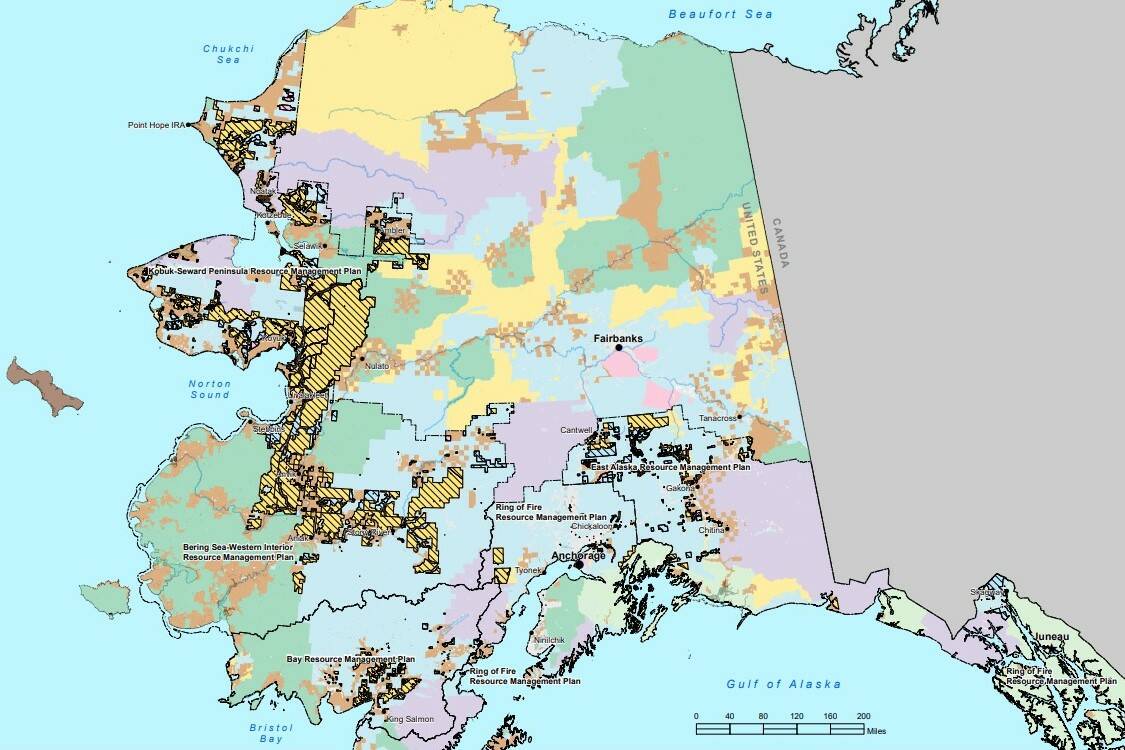

“Currently, there are approximately 1.2 million acres of available federal lands open to allotment selection,” the bureau said. “In this assessment, the BLM analyzed opening to selection an additional approximately 28 million acres of lands, currently withdrawn pursuant to the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act, within the Kobuk-Seward Peninsula, Ring of Fire, Bay, Bering Sea-Western Interior, and East Alaska planning areas.”

The assessment is part of a long-standing effort by Alaska Native veterans to obtain lands promised to them under the 1906 Alaska Native Allotment Act, a process interrupted by the passage of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act in 1971. Under the 1906 law, Alaska Natives were promised 160 acres of land but restrictions prevented many people from applying for the program until the 1960s. But at the time many of those allotments were granted, some Alaska Natives were serving overseas, particularly in the Vietnam War, and were unable to make their claim.

Over the years there have been efforts to convey the land but it wasn’t until the John D. Dingell, Jr. Conservation, Management, and Recreation Act of 2019 that a number of critical barriers to applications came down. Some of those lands were put under a stay in 2021 when the administration of President Joe Biden called for a review of orders under former President Donald Trump.

[Charity dinner and auction to benefit Ukraine]

But many veterans eligible for the land are frustrated with the amount of time it’s taken the federal government to transfer the land. George Bennett Sr. is a Vietnam veteran still waiting for his land transfer, and in an interview with the Empire Friday said he’s concerned the issue isn’t being solved fast enough for aging veterans to take advantage of the program.

“My biggest fear is two things, the age of the veterans and the legal aspect of what do the veterans do after (the transfer),” Bennet said. “We don’t want to leave our families hanging.”

Bennett also said there was cultural hesitation around estate planning.

“Us Native veterans don’t like to do that,” Bennett said. “In our culture, we don’t talk about that stuff.”

In addition to the slowness of the process, Bennett said the selection process itself was daunting and confusing. Even after the Central Council of Tlingit and Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska held a class to help veterans with the selection process, Bennett said he was still confused by the process. Bennett also said trying to get clarification from a large organization like BLM was also frustrating.

“That alone is a nightmare,” Bennett said. “Besides waiting for a response, they don’t even say we’re in receipt of your application. They don’t even do that, it leaves a lot of us the veterans wondering what’s the next move.”

Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland — the first Native American person to hold that position — said in May 2021 BLM would prioritize review of lands for transfer to Alaska Native veterans. The Bureau of Land Management did not immediate return request for comment.

According to maps from BLM, most of the lands available for selection are in interior Alaska. The nearest lands to Juneau available for selection are north of Yakutat on Icy Bay, maps show.

• Contact reporter Peter Segall at psegall@juneauempire.com. Follow him on Twitter at @SegallJnuEmpire.